Alaska lost a lawsuit that challenged a COVID-era emergency moose hunt. Now, it's appealing for a second time.

It's one of multiple cases in which the Dunleavy administration is clashing with the federal government over fish and game management, and over who has the ultimate regulatory power in that realm.

This edition of Northern Journal is sponsored by The Boardroom, a shared workspace in Anchorage. The Boardroom’s array of comfy and light-filled workspaces are a great change of pace from my home office; there’s good coffee and free kombucha, plus regular events like tacos and happy hours. Check out membership options here.

Northern Journal is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

In the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, the leader of a Southeast Alaska island village’s tribal government asked federal managers to open an emergency hunt, citing the community’s fears about having enough food. The request was approved by a federal management agency, the Federal Subsistence Board, and the harvest of moose and deer went ahead, supplying 135 households with meat.

But the opening of the hunt, in 2020, also prompted a lawsuit from Alaska Republican Gov. Mike Dunleavy’s administration — which is now, for a second time, appealing a defeat it suffered in federal court against the Biden administration, in the latest development in an ongoing feud over management of fish and game.

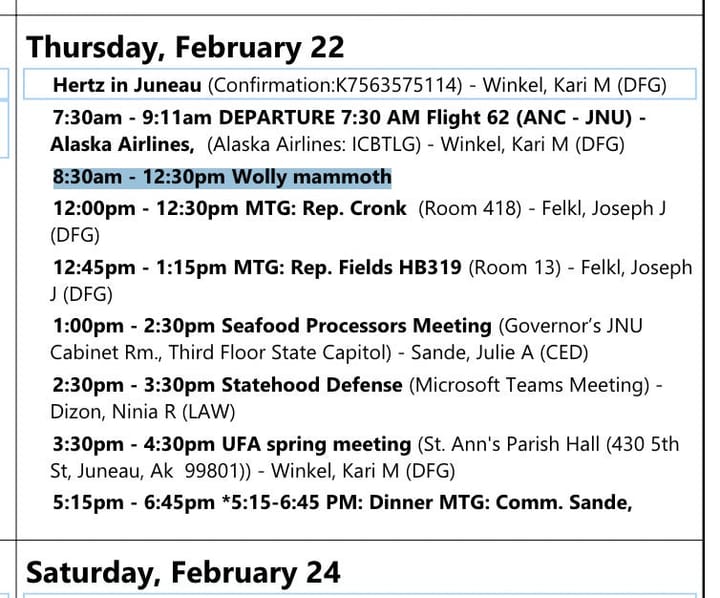

Dunleavy’s administration filed its notice of appeal Thursday, two months after U.S. District Court Judge Sharon Gleason ruled that the Federal Subsistence Board acted legally when it authorized the hunt of up to four moose and 10 deer.

The state’s four-page notice doesn’t include the specific legal basis for the appeal. But a spokeswoman for the Alaska Department of Law, Patty Sullivan, said in an email that the action is to “protect against federal overreach of game management on public lands.”

A spokesman for the U.S. Department of the Interior, which houses the subsistence board, did not respond to a request for comment. Nathaniel Amdur-Clark, an attorney for Kake’s tribal government, which intervened in the case in defense of the board, said it’s “disappointing but not surprising that the state is dragging this on.”

The underlying lawsuit is one of multiple cases in which the Dunleavy administration is clashing with the federal government over fish and game management in Alaska, and over who has the ultimate regulatory power in that realm.

State lawmakers have budgeted millions for an ongoing “statehood defense” program that’s grown to include lobbyists targeting U.S. Congress and federal agencies, along with lawyers coordinating strategy.

Dunleavy’s administration is also asking for an extra $300,000 in next year’s budget to hire two new specialists to monitor Federal Subsistence Board actions and support the state “in opposing federal overreach,” according to budget documents.

In the 2020 lawsuit challenging the Kake hunt, Gleason, the judge, originally rejected the state’s case, saying it was moot because the harvest had already ended. A Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals panel disagreed and issued a ruling last year asking Gleason to consider the Dunleavy administration’s underlying legal arguments against the harvest.

Those arguments tie into a decades-old conflict between the state and federal governments over management of and access to subsistence harvests.

A 1980 federal law, the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act, or ANILCA, requires that rural residents, who are largely Alaska Native, be prioritized in the management of subsistence harvests of fish and game.

But the Alaska Supreme Court, in a landmark 1989 decision, interpreted the state constitution to bar such a rural preference, saying it amounts to an exclusive or special privilege. And Dunleavy’s administration objects to the rural priority, saying that urban Alaska Natives with ties to rural areas shouldn’t face limits on their subsistence activity.

Because it was approved by the Federal Subsistence Board, the 2020 Kake emergency hunt was open only to “federally qualified subsistence users” selected by the tribal government — meaning that the participants had to be rural residents.

The Dunleavy administration argues that the board lacks that legal authority to open such harvests in Alaska, saying that the rural priority under ANILCA is only triggered when managers need to limit or close harvests in times of shortage. That meant, Dunleavy’s administration argues, that the board has the authority solely to close or restrict harvests — not the power to open them.

Gleason, in her November ruling, said Congress, through ANILCA, charged the federal government with "protecting and providing the opportunity for continued subsistence uses on the public lands" by rural residents, and that the authority to open hunts is "necessarily implied."

Want to advertise in Northern Journal? My new ad policy is here. Email me if you’re interested.