Alaska Native corporations take fight over carbon credits revenue to court

A new lawsuit pits three of the state's huge regional corporations against three others, in a battle that could jeopardize a four-decade-old pact that's guided distribution of more than $2 billion.

A new lawsuit threatens to upend a landmark, four-decade-old revenue sharing pact that’s guided the distribution of more than $2 billion among Alaska’s Native corporations.

The litigation stems from an omission from the 121-page, 1982 settlement agreement that has long defused financial disputes between the 12 regional Native corporations: The deal successfully outlined how the companies should share income from exploiting resources like forests, but didn’t specifically contemplate what should happen with money earned by preserving them.

Northern Journal is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The new lawsuit, filed last month, hinges on a major new revenue stream that has generated more than $100 million for three of the regional corporations since 2016.

Juneau-based Sealaska Corp., Copper River Valley-based Ahtna Inc. and Gulf of Alaska-area Chugach Alaska Corp. have all put tracts of timber holdings into California’s carbon credits markets, which allow forest owners to get paid for keeping lands unharvested for 100 years.

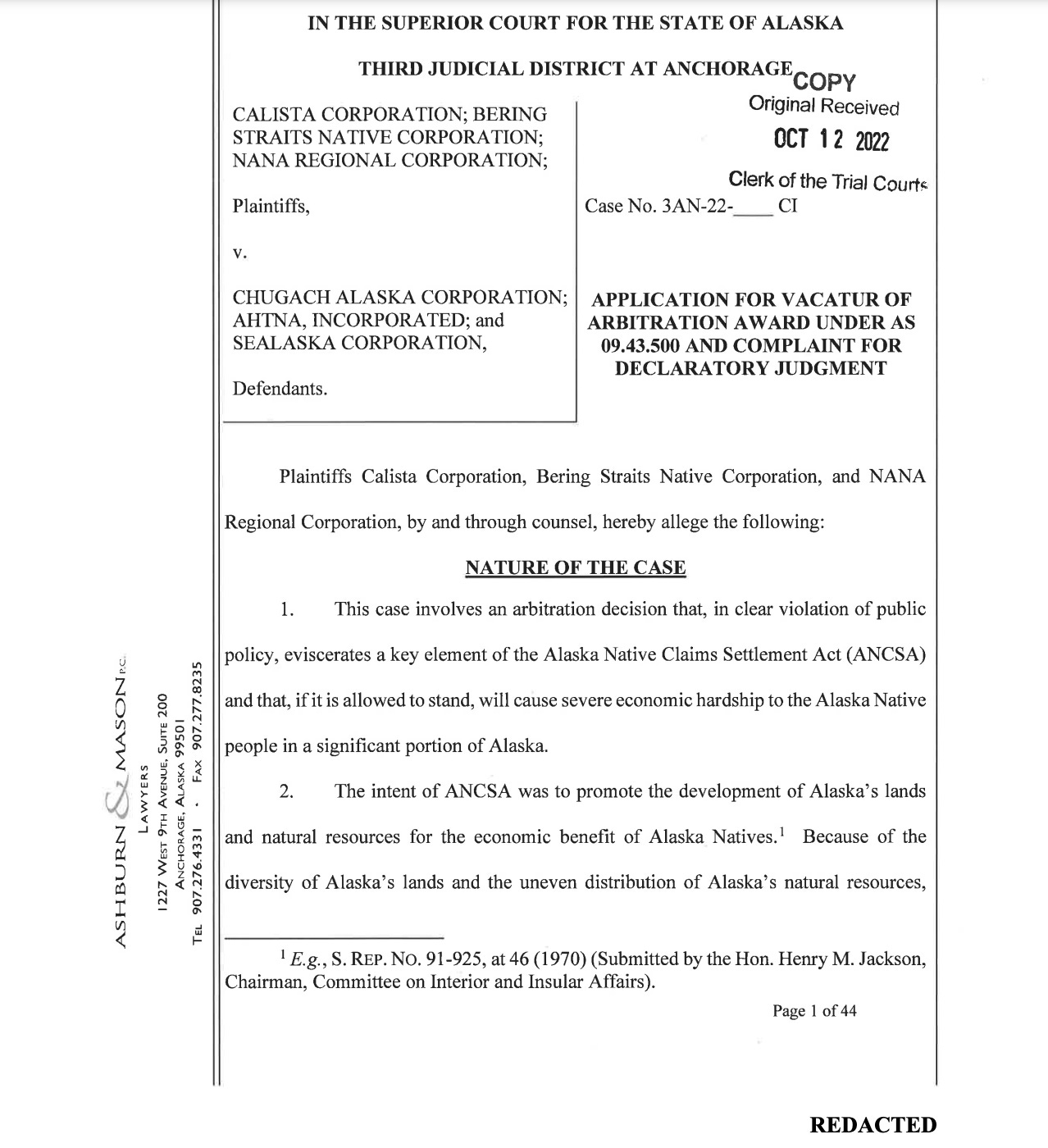

The plaintiffs argue that the 1982 agreement, and a 1971 federal law — the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, or ANCSA — that underpins it, require 70% of those carbon credit revenues to be shared among the rest of the regional corporations.

The 1982 agreement calls for revenue sharing disputes to be handled by a private, three-member arbitration panel. But after a unanimous panel decision in July that found the carbon credit revenues not subject to sharing, the three plaintiffs — Nome-based Bering Straits Native Corp., Kotzebue-based NANA Regional Corp. and Bethel-based Calista Corp. — appealed their case to the state court system.

Read the plaintiffs' complaint3.37MB ∙ PDF fileDownloadDownload

They’re asking Anchorage Superior Court Judge Jack McKenna to either award them a portion of the carbon credits money under the 1982 agreement — or, if he rules that the pact doesn’t apply, to invalidate it altogether.

“ANCSA is clear regarding the requirements for revenue sharing: 70% of all revenues received by each ANCSA regional corporation from their timber resources and mineral resources are subject to revenue sharing,” Matt Findley, an attorney representing Calista, said in a prepared statement. Calista and the two other plaintiffs, he added, “are pursuing this action to ensure the text and intent of ANCSA are honored.”

A Sealaska spokesman declined to comment on the lawsuit. Officials at Ahtna and Chugach, the two other defendants, didn’t respond to emailed requests for comment.

A new era of disputes?

ANCSA came as oil companies and elected officials were pushing for construction of the trans-Alaska pipeline five decades ago.

The pipeline project was stalled amid conflicting land claims by Indigenous groups that had not ceded their lands to the U.S. government. In response, federal lawmakers transferred some 10% of the state’s acreage to the 12 newly-formed, Native-owned corporations, as well as to more than 150 smaller village corporations.

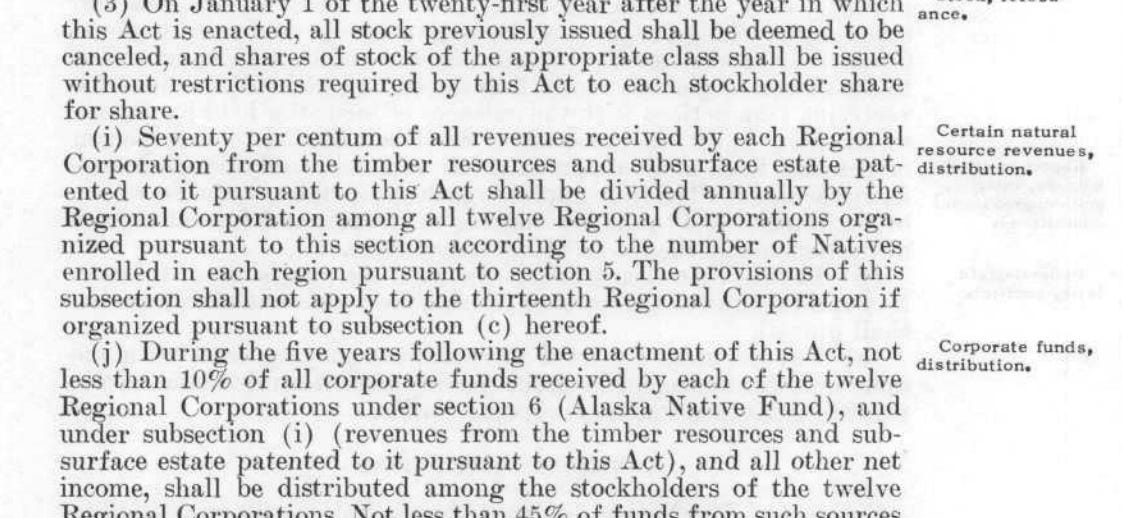

Lawmakers originally wrote the revenue sharing requirements into the bill to address disparities between the 12 regional corporations.

Some, like Arctic Slope Regional Corp., NANA and Sealaska, had valuable oil, minerals and timber on their lands. Other corporations, like Calista, obtained acreage that wasn’t as easily exploited.

The relevant section of the law, 7(i), was just two sentences and said only that 70% of “all revenues” from timber and subsurface resources should be shared among the regional corporations.

That left ample room for interpretation, particularly about how companies could deduct their costs from those revenues. Lawsuits over the details proliferated.

“Early in the process of interpreting what 7(i) meant, virtually every regional corporation was suing one another,” Roy Huhndorf, a former chief executive of Anchorage-based regional corporation CIRI, Inc., said in a phone interview.

After a decade of disputes over that section, the companies signed the court-approved, 121-page agreement in 1982 that elaborates on how sharing of oil and gas, timber and mineral revenues should work. Its sections more precisely define the types of revenue that qualify for sharing, deductions that are allowed and disallowed, reporting requirements and the arbitration process for resolving disputes.

The pact succeeded in nearly eliminating legal disputes over 7(i) revenue sharing, which has since distributed more than $2.5 billion between Native corporations. Disputes have occasionally arisen, like over the applicability of the law to potential oil-bearing lands within the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge that Arctic Slope Regional Corp. acquired in a land trade, but they have been rare.

The new lawsuit, filed last month, threatens to invalidate the 1982 agreement and launch a new era of disputes and litigation.

In their 44-page complaint launching the lawsuit, the plaintiff companies say that leaving the carbon credit revenues unshared “eviscerates” a key element of ANCSA and will cause “severe economic hardship” to Native people in different regions of Alaska.

The problem, they add, is especially urgent given that carbon markets “stand to become increasingly robust and profitable as efforts to combat climate change take on increased political salience."

A unanimous decision, appealed

The roots of the current conflict date back to 2016, when Ahtna, Chugach and Sealaska — along with a few smaller village corporations, which aren’t required to share revenues — began developing their carbon credit projects.

The exact amount the companies have earned since then is omitted from the lawsuit; attorneys have blacked out dollar values from legal documents at the request of the defendant corporations.

But Sealaska executives have said that their company alone has been paid more than $100 million for carbon credits.

The dispute, as required by the 1982 agreement, went to the arbitration panel before moving to the court system. Calista filed the initial request for arbitration in 2018, and eight other regional corporations subsequently joined the claim — all of them except Ahtna, Chugach and Sealaska.

Three arbitrators were chosen to consider the case — one by the requesting companies, one by the defendants and one chosen by the other two arbitrators. After pandemic-related delays, the arbitration panel heard closing oral arguments in Seattle in February.

The panel, which included longtime Alaska attorney and University of Washington law professor Jeff Feldman, returned their unanimous decision in July, saying that Sealaska, Ahtna and Chugach do not need to share their carbon credit revenue.

The decision has not been released publicly. But in October, three of the original nine corporations that asked for arbitration — Bering Straits Native Corp., Calista and NANA — filed their subsequent appeal to the court system and included passages from the arbitrators’ ruling in their complaint.

The arbitrators, in their ruling, cited two federal court decisions from the 1970s in determining that Ahtna, Chugach and Sealaska could keep their carbon credits income because they did not dispose of any interest in their timber resources, the complaint says.

While the corporations committed to maintaining carbon on their lands for 100 years, and to complying with a carbon credits enforcement regime, neither of those pledges involved a transfer of "legal or possessory interest in the timber resources," the panel said.

Alaska judges typically give arbitration decisions ample weight in appeals to the courts.

In the subsequent lawsuit, the plaintiff corporations argue that the carbon credit revenues are “plainly shareable.”

“Defendants are using a key ANCSA resource — their timber — and monetizing it, by agreeing to let this timber stand in exchange for payment from the carbon credit program,” the complaint says. In another section, it adds: “It makes no difference whether defendants received revenue from cutting their timber or whether the revenue is received from agreeing not to cut the timber. Either way, defendants receive revenue that is solely attributable to the existence of their timber resources.”

The plaintiffs are represented by a high-powered group of attorneys including former Alaska Attorney General Craig Richards and Findley, who’s argued cases before the U.S. Supreme Court.

NANA, whose massive Red Dog mine has produced huge revenues that it shares with other corporations, indicated in a prepared statement that the lawsuit is about fairness.

“NANA is one of the largest distributors of revenue under 7(i) due to Red Dog Mine,” spokeswoman Beth Rue wrote in an email. “Therefore, our board felt that it was important to challenge the arbitration decision.”

The corporations defending against the lawsuit have not filed a response in court.

McKenna, the judge in the case, has not yet scheduled a hearing.

This post has been updated to add a line about how the courts tend to defer to arbitration decisions.

For background on the 7(i) revenue sharing program, this Alaska Law Review piece by Aaron Schutt was helpful for me, along with a separate review piece that Schutt and his brother Ethan wrote on the 1982 agreement. I also wrote a story on the revenue sharing program and its importance to regional and village corporations last year as part of a series I did with Anchorage Daily News photojournalist Loren Holmes on the 50th anniversary of ANCSA.

Northern Journal is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.