Bottom trawlers that snagged orcas are testing new technology to avoid them

The trawl industry has scrambled to try to find a way to keep the whales out of their nets after nine were accidentally taken in 2023.

This story was supported by grants from the Pulitzer Center and the Alaska Center for Excellence in Journalism, and published by Northern Journal in partnership with the Anchorage Daily News and the Seattle Times.

In the Bering Sea, some killer whales are drawn to trawl vessels that catch large volumes of fish from nets pulled along the sea bottom.

The orcas often gather near below-deck chutes that funnel back to sea discards of whole fish. There, they may feast on halibut, a fish reserved largely for harvest by commercial long-liners and sport and subsistence fishers that cannot be retained by trawlers.

Hannah Myers, a University of Alaska Fairbanks assistant professor, has documented a different type of behavior that killer whales display around these trawlers. During a fall deep-water harvest that sometimes includes black cod — a favorite orca meal — the whales forage around the nets, according to Myers, who has led a three-year investigation of the whale’s behavior around bottom-trawl nets.

In May 2023, early on in her research, Myers — equipped with underwater recording equipment — spent a week aboard a Bering Sea trawler. She found that the whales, while down on the bottom, may have sampled fish that poked through the outer mesh of the trawl nets. They may have pursued fish in the front of the nets, or possibly entered the nets to gorge on dense concentrations of fish.

“I think it is very lucrative behavior,” Myers said.

It can also be perilous.

In 2020, two whales became entangled in bottom-trawl gear and died, their fate gruesomely captured in photos released to the environmental group Oceana under public record requests. In 2023, nine whales were accidentally taken by the bottom trawlers. Federal officials determined six of those whales died from their gear encounters, one was released alive but seriously injured, and two others were already dead before they became entrapped in the nets.

These deaths put a harsh spotlight on the bottom-trawl fleet, and gave new momentum to critics who have long raised concerns about the effects of the fleet’s net gear on a wide range of marine life.

The trawl industry has scrambled to try to find a way to keep the whales out of the nets.

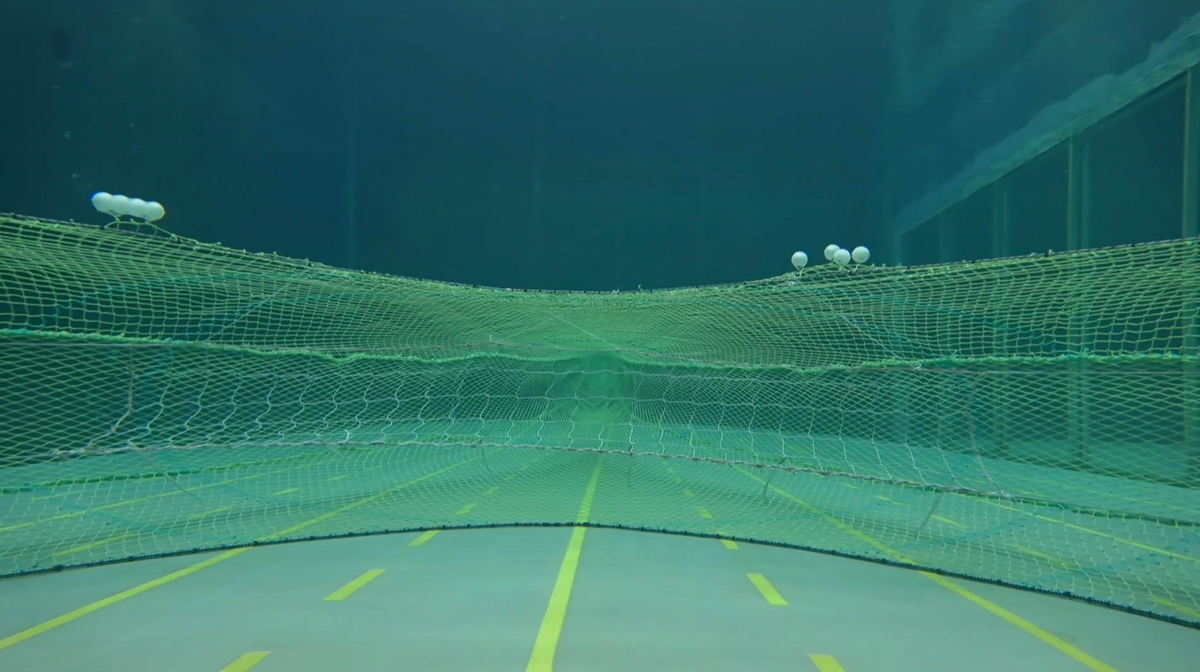

Bottom-trawl crews last year tested a kind of webbed fence that stretches across a wide swath of the trawl net mouth. This fence, made of an “echoreflective material” that whales can detect — is designed to act as a barrier to orcas while still allowing fish to pass over, under or through the broad gaps in the web barrier.

Even with the “excluders,” one whale last year died in a trawl net, which researchers believe was due to poor positioning of the fence barrier.

This year, more acoustic recordings have been taken by field technicians funded through a federal grant. They indicate the orcas still frequently hang around the undersea nets as they are towed along the bottom, and “feeding buzzes” indicate they still likely are finding fish, according to the study leader, Myers.

But, so far, there have been no reports of whales being caught in the Bering Sea deep-water trawl harvest.

“If they want to get by it, they could likely find a way past it,” Myers said. “I think it’s more like — ‘OK, there’s a fence there, we’ll feed somewhere else.’ ”