Fueled by trade tensions and foreign wars, a rush for an obscure mineral heats up in Alaska

A Texas company recently acquired 50 square miles of mining claims across interior Alaska. Now it wants to start trucking antimony — a mineral used in weapons and solar panels — to its processing plant in Montana.

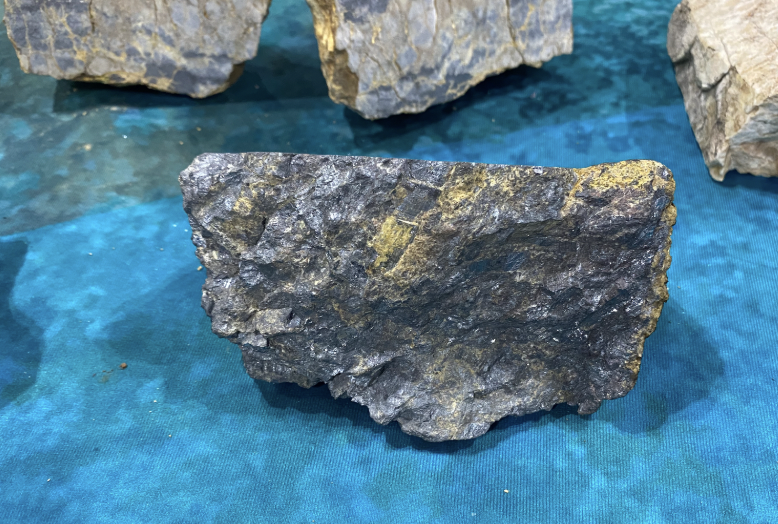

Alaska hasn’t produced antimony — a shiny mineral used in weapons, flame retardants and solar panels — in almost 40 years.

That could change this summer, according to the executives of a Texas company that has snatched up more than 35,000 acres of mining claims in Alaska.

Dallas-based U.S. Antimony Corp. is looking to the state as a new source of antimony for its smelter in Montana, the only plant in the United States that refines the mineral.

Alaska’s antimony, the company says, could help the U.S. overcome a recent ban on exports of the mineral from China, the world’s top antimony producer. Antimony is among several minerals — many of which are used in renewable energy — that the U.S. has sourced primarily from China and other countries in recent decades. Efforts to build more mines in the U.S. have accelerated amid worsening trade tensions and growing demand.

With no active antimony mines, the U.S. in recent years has imported roughly 60% of its antimony from China. Meanwhile, need for the mineral has surged as antimony-laden arms flow to wars in Ukraine and the Middle East.

The price of the mineral has quadrupled in the past year, rising from around $13,000 to $55,000 per ton.

U.S. Antimony is now expanding its Montana smelter and rushing to find more ore to supply it. Alaska is its “primary focus” for boosting production, an executive said in an interview last week.

In the past eight months, a U.S. Antimony subsidiary, Great Land Minerals, has acquired claims in three different areas of Alaska’s Interior: outside Fairbanks; near the small town of Tok; and along the Maclaren River off the Denali Highway, a scenic road that runs outside the national park.

U.S. Antimony says it’s looking to truck antimony ore some 2,000 miles from Alaska to its processing plant in Montana.That operation could start as soon as September, executives said on a recent call with investors.

“We can’t get that antimony from Alaska to Montana fast enough,” Joe Bardswich, U.S. Antimony’s chief mining officer, said on the call.

The company’s plans coincide with a separate effort by an Australian company to start up its own small-scale antimony mine near Fairbanks.

Felix Gold is seeking to restart production this year at a long-shuttered antimony mine that sits within a few miles of a residential subdivision, Hattie Creek.

The company also is eyeing prospects near the hamlet of Ester on the outskirts of Fairbanks — where U.S. Antimony’s subsidiary has claims, too.

The potential developments are generating a mix of responses locally.

Some residents worry about environmental impacts of mining and its potential to transform tranquil Fairbanks-area neighborhoods into noisy industrial sites.

“I don’t want to be all NIMBY. But it literally is my backyard,” said Lisbet Norris, who lives in Hattie Creek, about 10 miles north of downtown Fairbanks. “It’s just so close.”

Norris, a dog musher, runs sled tours on trails that cross Felix Gold’s claims on state land, and she’s concerned that mining might impede her business. She’s also worried about heavy industrial use of the dirt road that connects her neighborhood — and Felix Gold’s potential operations — to the rest of town.

Other Fairbanks residents, however, say they support mining in the area; some cite the town’s early history as a gold mining town and the potential economic benefits of new mines.

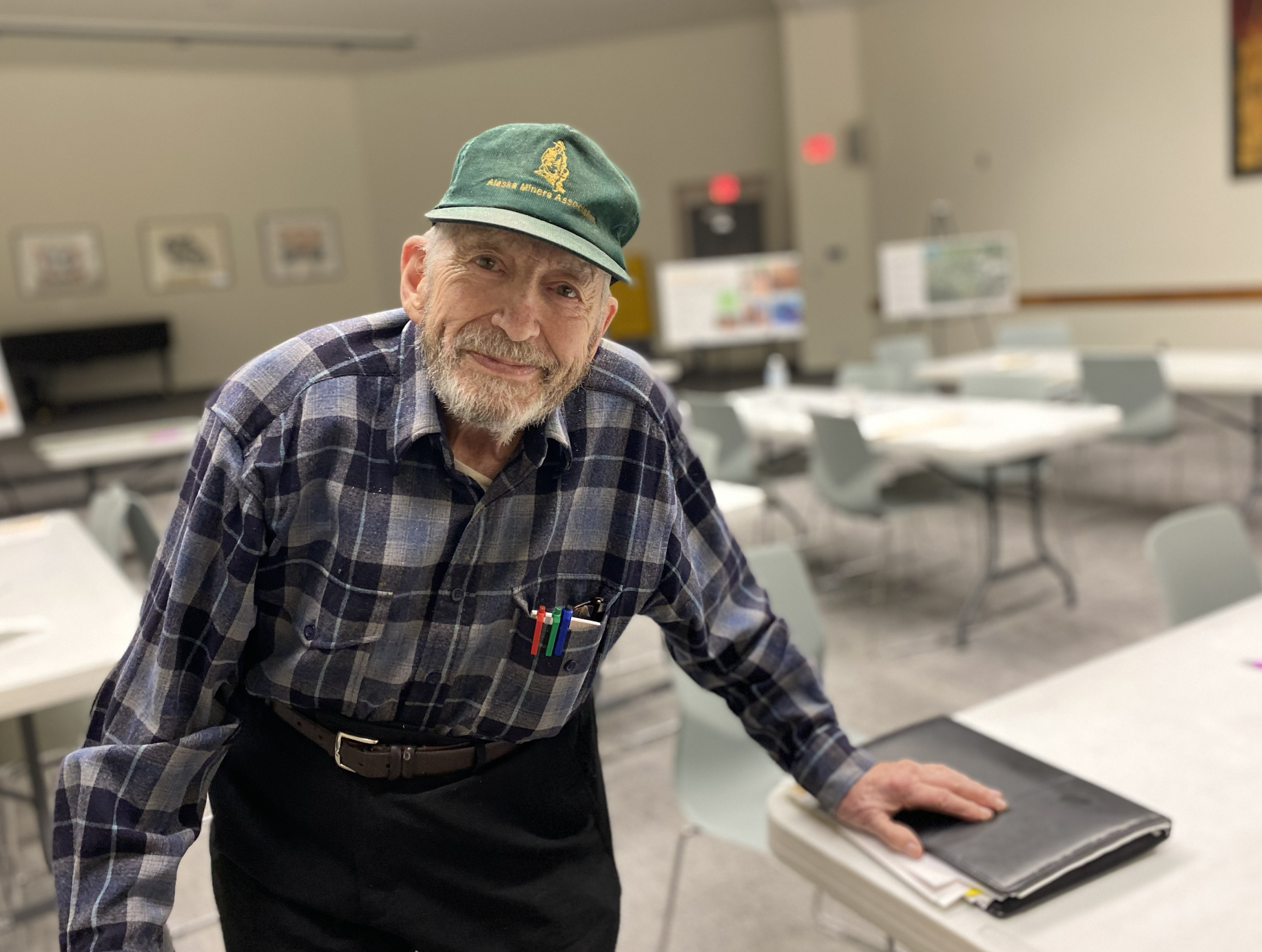

“It’s because of mining that Fairbanks is what it is,” said Roger Burggraf, a local prospector who owns some of the claims that Felix Gold has leased to study the feasibility of antimony mining.

Burggraf said he understands the concerns of people who live near gold and antimony prospects. But when they bought their properties, “they should have realized that if a mine developed, that might change their lifestyle,” he added.

Felix Gold has a permit only for mineral exploration, not active mining.

The company aims later this year to apply for additional state permits, and to finish studying the profitability of developing a small antimony mine near the Hattie Creek subdivision.

U.S. Antimony also has applied only for a permit to search for antimony, though it hopes to apply for more permits and start mining within a year. If its exploration efforts show a mine would be profitable, it would propose an underground operation, said Rodney Blakestad, U.S. Antimony’s vice president of mining.

The footprint would be small, more similar to the family-run placer mines in the area than to a large-scale hardrock mine, according to Blakestad.

“We’re not Fort Knox,” he said, referring to Fairbanks’ huge open pit gold mine.

But before U.S. Antimony begins mining, it wants to buy antimony ore from existing placer gold mines.

Antimony often appears alongside more-valuable gold, and gold miners have typically thrown it aside.

Now that antimony prices are surging, though, U.S. Antimony representatives say every little bit is valuable. A 25-ton truck could carry some $600,000 worth of minerals, Bardswich said in an interview.

That means small loads of antimony ore from shallow, exploratory trenches that the company intends to dig at its Alaska prospects this summer also could be worth driving 2,000 miles to the Montana smelter, company executives said.

In the meantime, they intend to launch an advertising campaign to share their interest in buying the mineral from placer miners.

“People don’t realize this: Gold is not the best mineral to be mining, if you’re looking for really good value,” said Blakestad. “Antimony is.”

Northern Journal's runs on reader support — voluntary paid memberships make up the majority of our revenue. Join if you can; if you already are a member, thank you.