Halibut managers contend with scientific uncertainty as fishery hits record lows

Scientists remain hopeful halibut will rebound, as in decades past. But they are unsure when that will happen.

This story is the last in a three-part series on Pacific halibut. It was supported by grants from the Pulitzer Center and the Alaska Center for Excellence in Journalism, and published by Northern Journal in partnership with the Anchorage Daily News and the Seattle Times. Read part one here and part two here.

Fish biologist Juan Valero went to work for the International Pacific Halibut Commission in 2008, and soon emerged as a dissident voice inside this organization that sets harvest levels for the U.S. and Canada.

Valero was convinced the commission models used to assess halibut had serious flaws that overestimated the size of the resource. He warned that this risked overfishing a halibut population that was already in cyclical decline.

Senior commission staff had a far more optimistic view. They were charged with presenting scientific research to six commissioners — three from the United States and three from Canada — whose vote each year sets the allowable catch. Their analysis indicated that halibut, while on a downturn, would soon surge.

“I was told that my concerns were unfounded. That it was too much like fearmongering,” said Valero, who was fired from the commission in 2012.

Valero’s clash with his colleagues marked a traumatic chapter in the 102-year-history of the commission, which is charged by international agreement with conserving a fishery resource that sustains a harvest important to both nations. It also underscores the challenges of trying to develop models that accurately assess the stocks of a fish with a complex life cycle that, even after more than a century of study, biologists are still struggling to fully understand.

Since Valero’s departure, halibut stocks have continued to drop, and now appear to be at or near record lows, according to a revamped assessment model that built on his earlier critiques. Staff scientists remain hopeful the halibut will rebound, as they have done in decades past. But they are unsure when that will happen.

Meanwhile, the commission has been forced, due to budgetary constraints, to sharply reduce the scope of ocean surveys that help assess the halibut populations.

The surveys are done aboard commercial halibut boats chartered by the commission. They used to be largely financed by the sale of fish caught by those crews. But these charters no longer generate enough revenue to pay for the full surveys.

This year’s survey, though slightly up from last year, covered less than 40% of the more than 1,200 sites that were checked — on average — from 2000 to 2021.

“It doesn’t make sense to do a weaker survey when the stock is at a low abundance. That’s exactly the opposite of what we would want from a scientific perspective,” said Ian Stewart, who joined the commission in 2012 as a senior scientist to head up stock assessments.

Commission staff and halibut industry representatives have scrambled to try to gain as much as $1.5 million in additional funding for an organization that has long been a high-profile example of U.S.-Canadian cooperation in resource management. And in August, the Trump administration approved a $513,000 grant to improve next year’s survey off Alaska, according to a State Department letter to the commission.

These survey results will help determine the future of the fishery that this year had the lowest harvest in more than a century.

“It’s absolutely pivotal for supporting all of the decisions that the commission has to make about how much fish can sustainably be caught,” said Jon Kurland, the Alaska regional administrator for NOAA Fisheries who chairs the commission.

Dramatic decline

The 1923 convention that created the International Pacific Halibut Commission came at another perilous time for the fishery. Expanding fleets that deployed thousands of miles of longlines with baited hooks pummeled prime fishing areas. As catch rates imploded, they moved on to the next.

“The youth and giant growing strength of our civilization is nowhere more vividly shown than in this reckless reaching out into the age-old treasures of nature for food,” wrote William Thompson and Norman Freeman in an early history of the halibut harvests written for the newly formed commission. “The fishery is not stable, not settled nor permanent.”

The commission was eventually empowered to limit the harvests, restrict the kinds of fishing gear that could be used to target halibut and allocate the catch among offshore areas of Alaska, British Columbia, Washington, Oregon and Northern California.

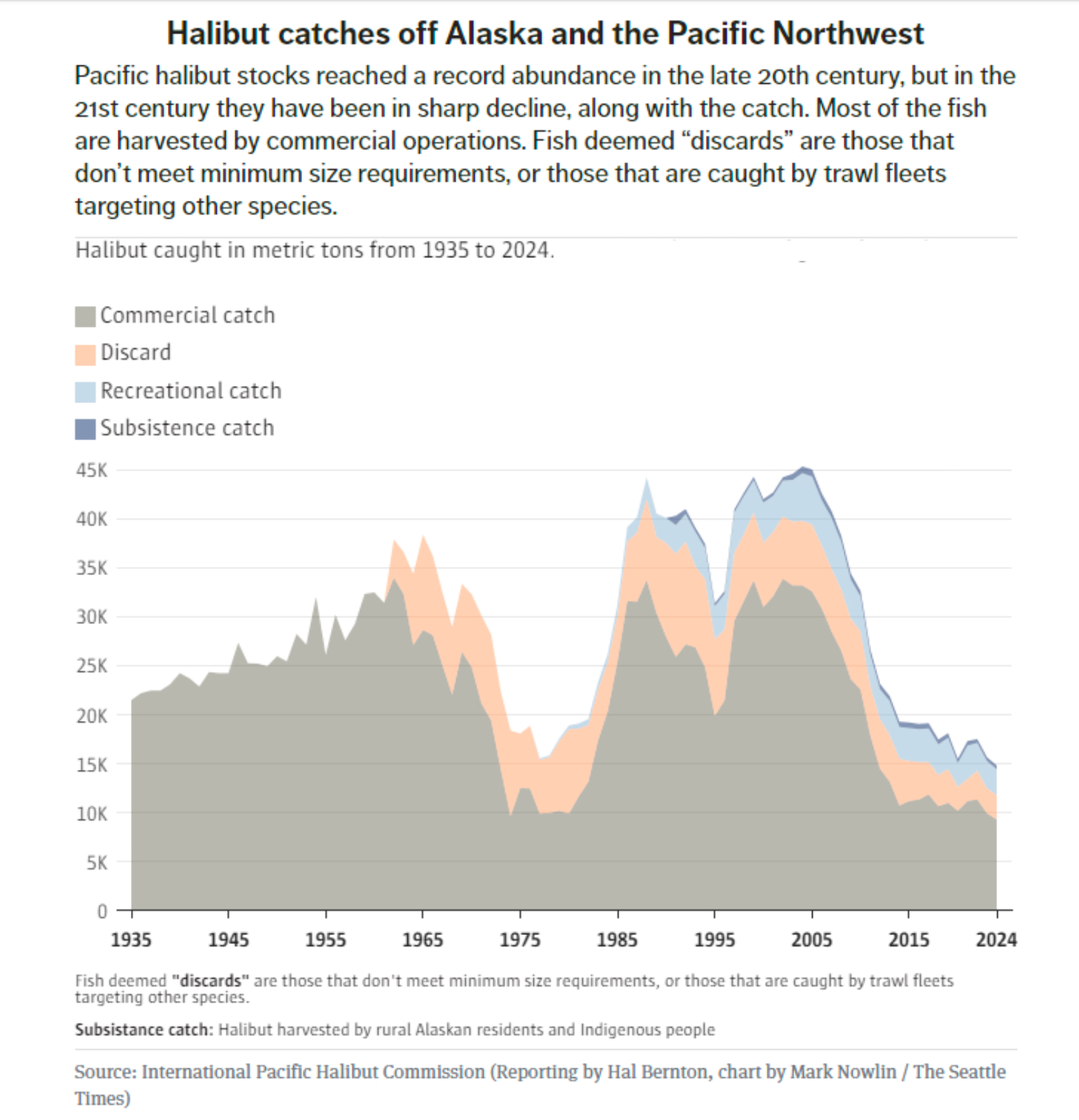

By the late 20th century, the halibut stocks had climbed to a record high as the commission gained an international reputation for fishery management.

This century has been much more challenging.

A key indicator of the health of the stock, the total estimated weight of females of spawning age, is down nearly 80% from the peak in the late 1990s, according to commission documents.

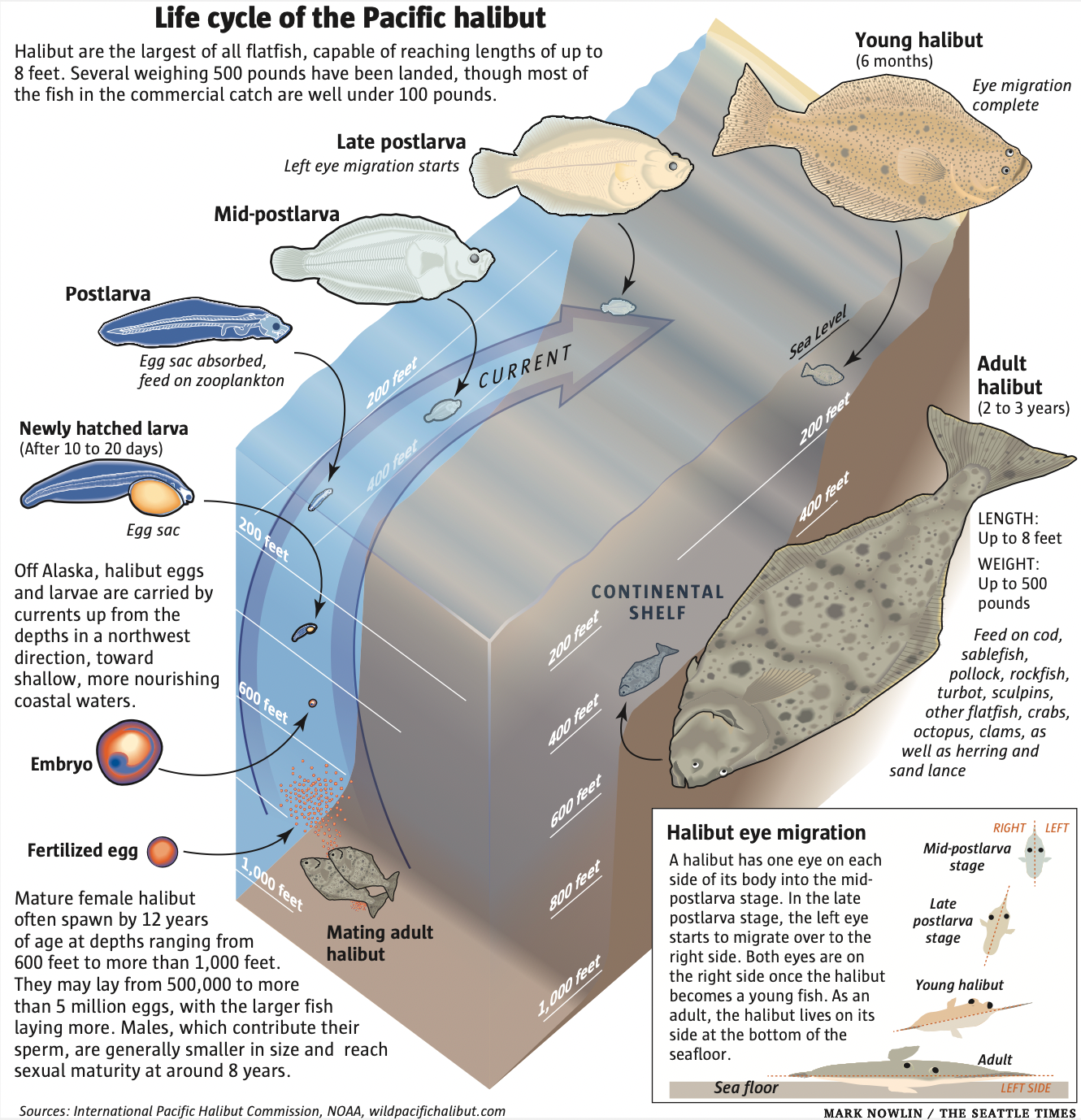

These females, which grow faster and much larger than males, spawn in deep water, often in the Gulf of Alaska. They may release up to several million eggs, which hatch into larvae that may ride the currents for hundreds of miles to reach nutrient-rich shallows favorable to their growth.

Every so often, for reasons biologists have yet to fully unravel, ocean conditions favor the survival of a year-class of offspring. There were several huge year-classes in the late 20th century, when the halibut population surged.

But during the past 25 years, survival rates of the juvenile halibut have, for the most part, been poor. And far fewer halibut have matured to sizes large enough to be harvested by fishers.

This downturn has come as climate change appears to have scrambled some of the ocean’s cyclical shifts, which include a set of conditions identified as favoring halibut.

Marine scientists have not found a strong link between climate change and the halibut decline, “though it’s definitely a wild card,” said Stewart, the commission biologist.

Researchers also have been tracking a dramatic downsizing of the average mature female halibut. A 19-year-old female, on average, weighed nearly 100 pounds in the late 1970s and less than 30 pounds in 2024, according to commission records.

Mature halibut also were smaller in the 1920s and 1930s, according to commission records. And some biologists, to explain weaker periods of growth, have focused largely on environmental influences that include a decrease in crab and shrimp that nourish halibut.

Other researchers say that fishing also has likely played a substantial role in shrinking the halibut size by continually removing some of the largest females.

That influence may have accelerated this century as stocks declined. In recent years, commission research indicated more than 70% of the coastwide catch was females.

“There are ecological questions when you constantly trim the biggest, healthiest females that potentially put the most energy resources in their eggs. Does that have an effect?” said Tim Loher, a biologist who worked at the commission for more than two decades.

Tracking bias

During Valero’s four-year tenure that ended with his 2012 dismissal, the commission grappled with something called “retrospective bias.” This is an obscure term but well known among fishery scientists. It results from the difficulties of developing complex models to estimate the size of the stocks, and refers to the revisions of earlier estimates that are made as new information is cranked into their calculations.

During the 1990s, as halibut stocks climbed, the commission model developed each year consistently underestimated them. But in the 2000s as the stocks decreased, the commission scientists found that the yearly models — when rechecked later — consistently overestimated the resource.

When Valero was first hired, senior scientists portrayed this bias as minor. They also repeatedly predicted the stocks would increase in the near future due to estimates of strong year classes of young halibut, according to a review of reports submitted to the commission in 2009 and 2010.

Valero had a starkly different take.

He concluded the models greatly overstated the strength of the halibut stocks, so the fishing fleets were hitting the resource much harder than indicated by the commission assessments.

Rather than rebound in the years ahead, he concluded stocks would continue to decline, according to commission documents that he authored.

“The fatal flaw was that estimates for future populations were always pointing upward. So they could say, ‘Don’t worry,’” Valero said.

Valero, a native of Argentina who attended the University of Washington’s School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, eventually gained a doctoral degree.

Valero was hired as a junior member of the commission staff, and his harsh criticisms of the models — documented in a series of reports — rankled some senior staff.

Valero said he was not allowed to brief the U.S. and Canadian commissioners on his analysis until a Seattle commission meeting in fall 2010, when his contrarian views were presented as an alternative assumption.

By 2012, Valero’s reports were getting far more attention from both senior staff and the commissioners, but he was let go in July of that year.

His letter of dismissal stated the commission had found a more experienced, qualified biologist to do his job, according to a copy of the letter.

It was a professional and personal blow that Valero still finds painful to talk about.

“I served at the commission at a time of serious internal differences of opinion, which should be welcome,” Valero said. “This is not a religion. We should always be open to alternative views.”

His dismissal triggered a backlash from his supporters within the commission as well as other fishery scientists who thought he was being unfairly targeted for his outspoken views.

“It is the responsibility of management … to admit and confront the uncertainties and problems in their assessment models, not to bury them,” wrote Ray Hilborn, a University of Washington fisheries professor who had taught Valero, in a letter to the commission, “I was therefore shocked to hear that Juan Valero had been given 24 hours to either resign or be fired. This appears to be a classic case of shooting the messenger.”

Bruce Leaman, who served as executive director while Valero was at the commission, said the retrospective bias turned out to be a “big deal” that “had a massive influence on where you think you are versus where you really are.”

Leaman said once an internal review was complete, Valero was able to present his findings to the commission. “It wasn’t like we were trying to suppress something.”

Stephen Hare, a senior scientist who had supervised the development of the flawed model, said he accepts blame for not being able to diagnose the cause of the bias that gave false hope of a “halibut increase on the horizon.” But he said he tried hard to fix the model, and never tried to hide the issue.

Hare noted that the harvest levels fell by 40% during his five years heading up the assessment team.

“Even with a more accurate model, it is difficult to imagine that catches could have been reduced much faster than that,” Hare said.

Even so, Valero says the harvest levels should have fallen much further.

How much farther should the harvest be cut?

Since Valero’s departure, the commission staff has undergone major changes in leadership.

Hare resigned in July 2012, the same month Valero lost his job.

After Hare left, Leaman called for stock assessors headed by the newly hired Stewart to undertake a major review. They uncovered some of the same problems earlier flagged by Valero in the stock assessment models. And based on their recommendations, the commission continued to cut harvest levels, which by 2014 had fallen to less than half the 2010 tally for the commercial catch.

Then in 2016, Leaman, after 19 years serving as the organization’s executive director, did not have his contract renewed by the commissioners.

Leaman was replaced by David Wilson, an Australian fishery scientist who worked for more than five years at the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission as well as other jobs in Pacific and Caribbean fisheries.

Stewart has continued to lead stock assessments.

To help estimate the resource, the team draws on information gathered from the longline surveys, a separate U.S. government-funded trawlnet survey of young halibut, and information gathered from the commercial catch. Then, Stewart’s team estimates the risk of various harvest levels.

“He’s widely respected around the world for the science he is doing,” said Linda Behnken, an Alaska commercial fisher who formerly served as a commissioner.

In recent years, with halibut in continued decline, the commission’s assessments have received more scrutiny.

The commission scientists have largely blamed poor environmental conditions for the continued decline in the halibut stocks.

Loher, the former commission staffer, says there should be more consideration of an alternative scenario — the possibility that fishing levels are still high enough to impede the stock’s resurgence, and more severe harvest restrictions are necessary.

The staff’s work is reviewed by a board of scientists established in the aftermath of the discovery of the flawed models flagged by Valero. During a June meeting, then-board chair Sean Cox, a British Columbia scientist, suggested the stocks already may be low enough to justify a designation of “depleted,” the point at which their recovery might be uncertain.

But commission staff had a much more optimistic take in September, when the review board reconvened for another meeting. They presented yet another set of freshly developed models. They indicated that halibut stocks were still not close to the dire level of depletion.

“It’s very encouraging. And, I thought, ‘OK, that helps me sleep at night,’” said Allan Hicks, a commission biologist who developed the models.

Northern Journal runs on contributions from readers. If you appreciate in-depth journalism like this and you're not already a paid subscriber, please consider a voluntary membership.