Climate change and a looming gas crunch are turning the heat up on Alaska utilities. Are they up to the challenge?

Clean energy advocates are increasingly criticizing Anchorage's electric utility for doing business behind closed doors. I went to a board meeting to see for myself — and was exiled from the room.

Northern Journal is a newsletter written by me, Anchorage journalist Nat Herz. It’s free to subscribe, and stories are also free to Alaska news outlets to republish through a partnership with the Alaska Beacon.

My goal is reaching the broadest possible audience of Alaskans. But if you can afford it, please consider supporting my work with a $100 annual or $10 monthly voluntary paid membership — these are currently my only sources of revenue for this project. Your support allows me to stay independent and untethered to the demands of the day-to-day news cycle. If you’ve already subscribed, thank you.

Last week, I decided to attend a board meeting at Chugach Electric Association, a cooperative that’s Alaska’s largest electric utility and serves more than 90,000 members in and around Anchorage.

After I filled out a form, an employee sent me a Zoom link. I responded that I wanted to attend in person, as both a member of the cooperative and as a reporter.

Seven minutes later, my phone rang.

It was Julie Hasquet, Chugach’s senior manager for corporate communications — a veteran public relations professional who worked as Mark Begich’s spokeswoman when he was a U.S. senator.

Hasquet wanted to know what I was up to. After some back and forth, I explained that I’d heard some complaints and criticism about the way Chugach is run, and wanted to attend a board meeting to see for myself.

Hasquet asked me who I’d been talking to, and if I was being “straight” with her; I said I was. Then, a few hours later, she sent a follow-up text, asking me to refrain from approaching board members and employees during the evening meeting.

“They have a pretty packed agenda,” she said. “The request has come to me that any questions you have be emailed post-meeting, because there won’t be any opportunities for questions during the meeting. Thank you.”

Basic journalistic principles say that when someone questions your approach, or tries to dictate how you ask your questions, it usually means that your approach and your questions are on target.

Up until I received Hasquet’s text, I didn’t actually have any questions for board members. But now I did.

A new landscape for utilities

To understand why you should care about Chugach, let’s back up.

If you pay for electricity in Anchorage or on the northern Kenai Peninsula, you’re writing the cooperative a check every month: The bill for my small Anchorage home, for example, is about $40.

Until recently, I didn’t spend too much time reflecting on where that money was going, and I suspect that most others didn’t either — people generally seem to accept their utility bills as a mildly painful constant in their lives. Across the country, utility members and shareholders have come to expect conservative management and consistent rates — not visionary thinking.

But two things have changed dramatically in the past few years — one on a global scale, and one on a local scale — that are driving people to pay more attention.

First: The rapidly warming planet and the plummeting cost of wind and solar power have put pressure on utilities to reduce their dependence on fossil fuels. Second: The major natural gas producer in the Anchorage area, oil and gas company Hilcorp, has warned its utility customers that they shouldn’t count on a guaranteed supply of fuel for more than a decade.

Those were two of the reasons that I wanted to hear Chugach’s board discussions last week.

The same issues are also the focus of a small group of renewable energy and transparency advocates who have tracked the actions of Alaska utilities for much longer than I have. Some of them are worried that the utilities are poised to make expensive investments in hydroelectric projects or liquefied natural gas imports that could rule out potentially cheaper sources of renewable power.

[Related: Could oil-rich Alaska be forced to import LNG? Two utilities are looking into it.]

“The decisions that Chugach and all of the other cooperative utilities make — they are making energy policy for all of us,” Antony Scott, an analyst at Renewable Energy Alaska Project, told me this week. “And we’re at a point now where some big decisions are going to be made that will have potentially very long-lasting consequences.”

Scott is a former member of the Regulatory Commission of Alaska, which oversees the state’s utilities. He has a doctorate in natural resource economics and two masters degrees, and he was one of the people I was referencing when I told Hasquet that I’d been hearing questions about Chugach’s governance.

One of Scott’s central critiques — and a position shared by other critics — is that Chugach’s board spends far too much time meeting out of public view, in what’s known as executive session.

Scott publicly testified about this at a board committee meeting earlier in the month, and his criticism got my attention for the same reason Hasquet’s message did: In the experience of most reporters, the more an entity tries to keep its business secret, the more likely it has something it’s trying to hide.

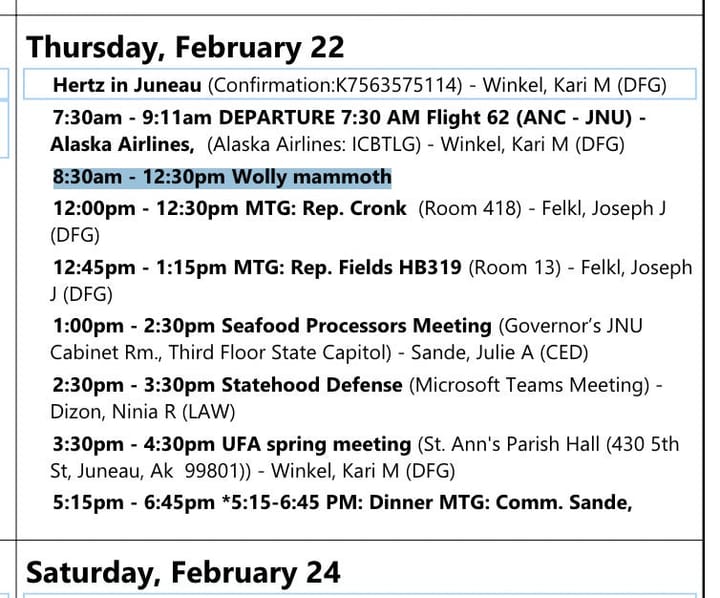

After I arrived at Chugach’s boardroom last week, I listened as staff presented to board members on subjects like the cooperative’s decarbonization plan, and a community solar project.

Then came the most interesting part of the agenda — a discussion about potential new legislation at the state Capitol to set clean energy targets, which was a contentious proposal for utilities when Gov. Mike Dunleavy introduced it last year.

After that agenda item, the board was set to discuss its five-year strategic plan, and its operating and capital budgets.

But I, and the other members in attendance, didn’t get to hear those parts of the meeting.

Instead, we had to leave the room, because the board voted unanimously to hold those discussions in private.

“Fresh air and daylight”

Alaska’s Electric and Telephone Cooperative Act, echoing the state’s Open Meetings Act, gives utility members — like myself and anyone else in the cooperative — the right to attend board meetings.

There are four exemptions that allow board members to use executive session. But they’re limited and specific: personnel matters, advice from attorneys, discussions that could affect a person’s reputation or character, and “matters the immediate knowledge of which would clearly have an adverse effect on the finances of the cooperative.”

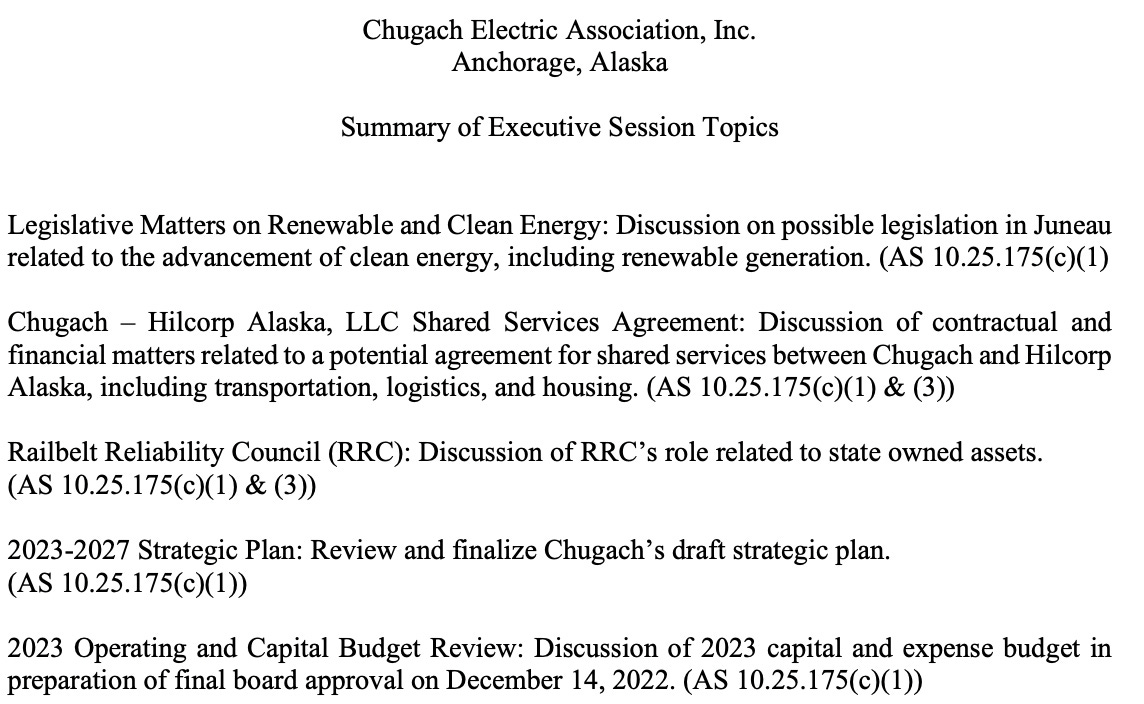

At the meeting I attended, Chugach’s board used that last exemption as a basis for holding executive session on five different items. Those items included the five-year strategic plan — which the board subsequently approved and published after the meeting — the operating and capital budgets, and "possible legislation in Juneau related to the advancement of clean energy, including renewable generation."

My reaction was: hang on. Merely talking about renewable energy bills that could be introduced in next year’s legislative session would “clearly have an adverse effect” on Chugach’s finances?

This sounded extremely unlikely to me; it also sounded implausible to a lawyer with experience in media law whom I asked about it.

This is far from the only time Chugach and other Alaska utilities have drawn attention for their use of executive session. Just one week before, Scott, the renewable energy analyst, had questioned the Chugach board's operations committee as it went into executive session to discuss its decarbonization goals and its gas supply.

A separate working group with multiple utilities, formed this year to discuss Alaska's impending natural gas crunch, is holding all of its meetings in private.

After last week’s Chugach meeting, I called all seven board members to ask about their votes to enter executive session. Several didn’t return my calls, and I ultimately reached just three of them; one was Sam Cason, a former state attorney.

Cason said that once the executive session began, there was a “spirited conversation” about whether the discussion about clean energy legislation should have happened in public. And he agreed with some of Chugach’s critics that the cooperative could be more transparent, saying that “there’s a tendency to want to keep private things that should be subject to fresh air and daylight.”

“I don’t always agree with the call to go into executive session,” Cason said. “And I welcome the scrutiny.”

Bettina Chastain, Chugach’s board chair, was a little more defensive, at least at the start of our conversation.

“Everything that’s available that doesn’t compromise the organization, we put into public session,” she said. “And then we go into executive session to discuss details of things under those topic areas that could compromise the organization.”

Chastain referred detailed questions about the use of executive session back to Chugach staff. Hasquet followed up with an email saying that “due to the privilege associated with executive session discussions,” the cooperative couldn’t provide any justification beyond citing the open meetings exemptions in the Electric Telephone and Cooperative Act.

“We stand by our assessment that the materials and information discussed in executive session met the requirements,” she said.

As I spoke with Chastain, a longtime engineering and oil and gas consultant, I could tell that she was uncomfortable. But she still stayed on the phone for more than 45 minutes.

Chastain acknowledged that she’d asked Hasquet to direct me to send questions in writing, but not because she was afraid of them, she said. Instead, she said, she was worried about getting pulled into an interview during a break and letting the tightly packed agenda go off track.

Chastain sounded frustrated about the criticism that Chugach has been hearing about transparency and executive sessions, saying it was coming from “outside organizations — it’s not necessarily member comments.” In the eight years she’s served on the board, she added, the utility has been doing its business the same way.

“This is the way we do our business,” she said. She added: “I'm very cognizant of my role, and we're not hiding anything.”

I was struck by Chastain’s sincerity. And I think she’s probably right that Chugach has not changed the way it does business recently — instead, its business is just getting more attention.

I’m just one example of that: For the past eight years, I didn’t think enough about my own electric bill, or the cooperative's importance to Anchorage residents and businesses, to attend or track a single board meeting. While Chugach is Alaska’s largest electric utility, Hasquet said that it can go a year or more without a reporter attending a meeting.

But now, as Alaska contends with a natural gas crunch and increasingly dramatic impacts from global warming, I care much more about what Chugach is doing. So do a growing number of advocates, policymakers and business figures.

Which means that the approach and vision that worked for Chugach for the past eight years may be very different from the approach and vision it needs to get through the next eight years.

As Chugach and other Alaska utilities sort through these challenges, Scott said it’s imperative for them to do more of their business in public — which he thinks will help ensure that their decisions are the right ones.

That’s especially important, he added, as the utilities consider their future mix of power sources, and use cost models and assumptions that pit renewables against natural gas.

“I can tell you: As a former bureaucrat, when you have to show your work in public, you work a whole lot harder to make sure that it’s pretty unimpeachable,” Scott said.

“Maybe all of the decisions are the best that you can possibly make, and I am wasting my time,” he said. But, he added, “I’d like to know that.”

Northern Journal is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.