In Alaska, fishing skippers and hungry orcas vie for halibut pulled from the deep

An intensifying arms race between fishermen and the whales has crews testing cutting edge equipment.

This story is part two in a three-part series. It was supported by grants from the Pulitzer Center and the Alaska Center for Excellence in Journalism, and published by Northern Journal in partnership with the Anchorage Daily News and the Seattle Times. Read part one here.

UNALASKA, Alaska — The orca pod that forages in the waters just north of this Aleutian island are quick to swarm any halibut boat with a skipper foolish enough to drop lines in their domain.

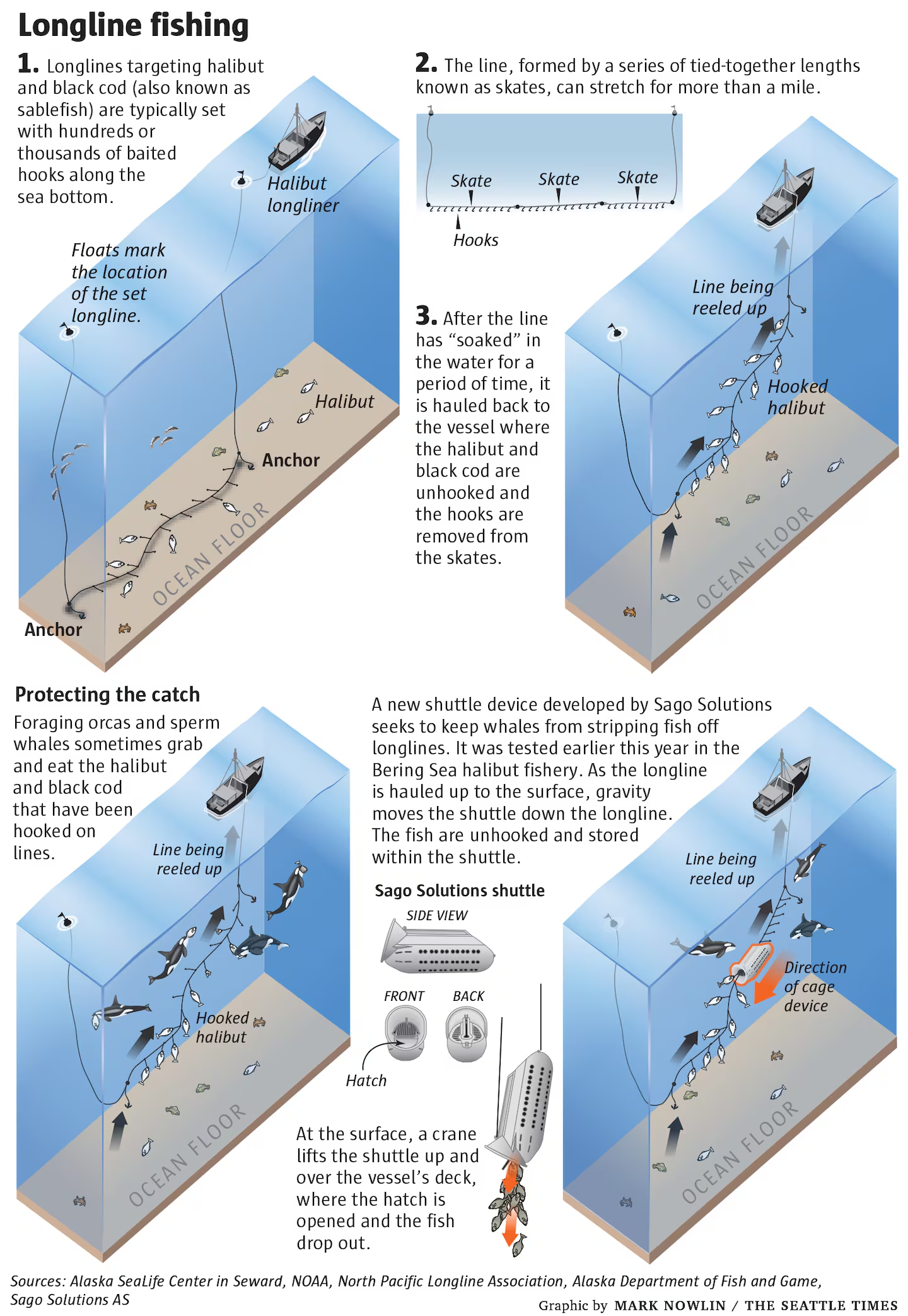

As the lines are pulled up, and fresh-caught fish near the surface, the whales, in a well-honed feeding ritual, pick them off the hooks.

Skipper Robert Hanson’s lines have been hit by lots of the killer whales that dwell in the Bering Sea. He has found the Unalaska pod to be the most savvy, skilled and aggressive — leaving just traces of halibut, the largest of which could have netted Hanson hundreds of dollars apiece.

“Most of the time, you get nothing. Sometimes a lip, or a half a fish, if they get full,” Hanson said. “They are particularly good at what they do.”

For the past 20 years, Hanson has sought to avoid feeding these whales and prospected for halibut elsewhere. But during a May fishing trip, Hanson dared to set his lines near these whales as part of an eight-day sea trial to test a new defense, an aluminum “shuttle” resembling a small submarine.

After halibut are hooked near the sea bottom, the shuttle is designed to glide down the lines and unhook the fish, securing them inside the metal enclosure before killer whales have a chance to feast on the catch.

Fishing crews across a broad expanse of the world’s oceans, ranging from the South Atlantic to the North Pacific, report unwelcome encounters with whales.

The fishing grounds off Alaska are a hot spot, a sometimes uneasy mixing zone for commercial fleets that collectively produce the United States’ largest seafood harvests, and whales that also depend on this bounty.

Alaska orcas, as well as endangered sperm whales, have for decades stripped the oil-rich black cod (also known as sablefish) off longlines.

Both orcas and sperm whales also relish Pacific halibut, a big, meaty flatfish. And in the Bering Sea, in recent years, some orcas have started to target the livers of Pacific cod.

During a spring fishing trip, the crew of the Oracle encountered orcas as they brought in pots filled with black cod. (Video by Baxter Cox)

“We would get the head back and a gut pile that had been chomped,” said Reynaldo Rubalcava, who captains the Lilli Ann, a Bering Sea vessel that harvests Pacific cod. Rubalcava estimates that his vessel’s catch declines by about 20% when the whales are present.

Surveys of fish-eating orcas estimate — at a minimum — almost 1,000 whales roam the Bering Sea, and more than 900 dwell in the Gulf of Alaska, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Fisheries. They are divided into numerous pods, and are far more plentiful than the 74 endangered southern resident orcas that frequent Puget Sound in three pods.

Alaska fishers have tried many, often unsuccessful, tactics to try to shake off whales, including moving dozens of miles to new areas and blaring rock music. Back in the early 1980s, a few threw sticks of dynamite into the ocean. Several took up arms, firing guns at the whales, according to Craig Matkin, an Alaska whale researcher — founder of the North Gulf Oceanic Society — who documented some of the shootings.

Off Alaska, the whale predation has been severe enough to prompt some fishers to give up the use of vulnerable longlines. Under federal rule changes in the Bering Sea — and later the Gulf of Alaska — they were able to switch to baited traps known as pots that can be set along the sea bottom to efficiently catch black cod.

Many of the black cod fishers now use “slinky pots,” which are collapsible and soft-sided so they can be stowed compactly on small boats.

For black cod, this transition has largely been a success, reducing the conflicts between whales and fishing crews.

Editor's note

Some of the visuals included in this story were taken by Baxter Cox, a halibut fisherman who documented his life at sea on Instagram. Cox sometimes crewed aboard the Oracle where reporter Hal Bernton and photojournalist Loren Holmes met him in late May. He died Sept. 3 in an accident aboard another vessel, the Halcyon.

But the pots do not efficiently catch the much larger halibut.

And in recent years, the Unalaska-area orca pod learned how to tear into the slinky pot mesh to dine on black cod. Other whale pods also have started to breach the slinky pots. This raises the possibility that the Unalaska pod acts as a kind of innovation hub, developing new tactics, then spreading them to other pods.

“They do mingle because the males move into other pods to mate and stuff,” said Matkin, who has studied Alaska’s orca whales for decades. “And they sometimes mingle just to be social.”

The whale predation has prompted — at considerable cost — a redesign of the slinky pots with stronger mesh, according to Alex Stubbs, a marine biologist who fishes for black cod and developed this gear. Even these sometimes suffered damage, so there likely will need to be another more expensive retrofit with stronger mesh.

Hard pots with sturdy steel frames once appeared to be a more secure option for bigger boats with enough space to carry them on deck.

Bering Sea fisher Bill Wahl said he used hard pots for 16 years without losing any black cod to whales. He frequently encountered the whales circling the boat as the pots were hauled to the surface. Sometimes, they were so close, he could see their noses rub against the tow lines for the pots.

“They were just hanging out, and it was a pleasure,” Wahl recalled.

For Wahl, things changed this May as he dropped pots in waters close by Unalaska.

Small groups of orcas dived, then went to work ripping the soft bottom from dozens of pots. The black cod were able to swim free, at least until the whales snapped them up.

Baby orcas would join in on some of the dives.

“They’re training them how to open the pots the same way they trained them to take fish off a hook,” Wahl said.

Testing the shuttle

Omar Sørvik is a gray-haired Norwegian veteran of the fishing industry whose career took him to Alaska, then to Argentina and Chile, where longliners in 2008 were struggling to get toothfish past orcas swarming their gear.

Toothfish generally are hooked at extreme depths that killer whales cannot reach. But as the longline gear was hauled back to the surface, the whales were quick to pounce.

“The killer whales were so bad we couldn’t continue,” Sørvik recalled.

Rather than give up, Sørvik helped to develop the shuttle to use in the toothfish harvest.

For the longliners working off Chile, the shuttle experiment appeared to have been a success. Propelled by gravity, it is able to move down the line, grabbing the fish close to the bottom — before the whales had a chance to pick them off.

Sørvik is the co-founder of a company — Sago Solutions — formed to market the shuttle. Sago stands for “Sorry Amigo Game Over,” Sørvik’s boastful taunt to the whales.

Sørvik flew to Unalaska in May. There, he joined three biologists from the International Pacific Halibut Commission, along with skipper Hanson and four crew members, in the May deployment of a smaller version of the shuttle aboard the Oracle.

The boat’s charter and other expenses were funded through a grant from NOAA Fisheries. The Oracle carried two pods, an underwater camera and other gear to help monitor the performance, which the researchers hoped would be strong enough to warrant further experimentation by fishers.

“If it works, it’s potentially going to open up areas that they haven’t been able to fish in for years because of the whales,” said Ian Stewart, one of the three commission staffers.

For the scientists’ charter, the 58-foot Oracle was a lot more crowded than a typical fishing trip. Every spare bunk was occupied. The crew shared deck space with researchers in a joint effort to find the safest way to set the pod in the water and bring it back up amid spring squalls.

Crewman Jack Demmert, a Tlingit tribal member raised in the coastal Alaska town of Yakutat, was intrigued by the shuttle. He had seen the toll that orcas could take on the halibut catch — and his crew-share income — on Bering Sea trips last year aboard the Oracle.

But Demmert also was uneasy about framing the problem as “whale predation” — as if the hooked halibut were longliners’ property. He grew up with a reverence for the orcas that was nurtured by his grandfather, a small boat halibut fisherman who would sometimes offer a portion of his catch to the whales.

“He would tell me, ‘You thank them. You are doing your work. They are doing their work,’ ” Demmert recalled. “The way we see it. We are allowed to exist in their territory by an unspoken agreement. There is mutual respect that we have with them.”

Whales, also, on occasion, have appeared ready to cede some of their catch to humans. A research paper published earlier this year detailed 34 attempts by orcas in different parts of the world to give some of their prey — including six species of fish — to people in boats, swimming in the water and onshore.

Skipper Hanson, however, was not going to make any gift of his catch as a peace offering.

“You want to think you are altruistic. But that’s not the case. As soon as they find out you’re going to feed them, they will hound you relentlessly … relentlessly.”

Mixed results

During the sea trial, the research scientists first wanted to learn about the shuttle’s performance when no whales were present.

They found the Sago was able to move along the line, retrieve halibut, stow them away and bring them back on board.

“Everything worked,” said Stewart, the commission scientist.

But it’s unclear just how well the shuttle functioned when whales were around.

At least on one occasion, the results were encouraging. A swath of line protected by the shuttle caught some halibut. Another swath of unprotected line came up with lips, according to Stewart.

The shuttle’s toughest challenge came on the last day at sea. That’s when the Oracle had an intense encounter with the Unalaska pod of whales.

Only two halibut came up in the shuttle, and one halibut on unprotected stretches of line.

Stewart, the commission biologist, said that the research team is still analyzing the pod’s performance that day.

Hanson says this fishing spot was well within the whales’ diving range. So, at least on this day, he thinks these amigos may have outwitted the Sago device. The whales may have gone down to the bottom, then grabbed some of the hooked halibut before the line could be pulled through the shuttle.

But Hanson has not given up on the Sago. He hoped to conduct more tests on an October fishing trip in a different part of the Bering Sea.

There, he expected to face another orca pod, one less motivated than the Unalaska-area pod.

“I think they will leave us alone. Who knows for how long?”

Epilogue

In his October fishing trip, Hanson encountered some rough weather, and was only able to deploy the shuttle during five sets of his longlines. The fishing was poor and the crew caught only a few halibut. But the shuttle kept those fish safe from whales drawn to the boat.

“We successfully deployed it, but I just didn’t find any fish,” Hanson said.

Northern Journal runs on contributions from readers. If you appreciate in-depth journalism like this and you're not already a paid subscriber, please consider a voluntary membership.