Interesting Stuff: Researchers eye low-carbon fuel from Alaska rocks, Biden official visits a B.C. mine and election results boost Ambler mining company.

We've got items on the proposed Ambler road and neighboring mines, a project to research low-carbon fuel that could come from Alaska mines and Indigenous challenges to mining projects in British Columbia and the Nome area.

Interesting Stuff is a periodic digest with news items and updates on stories that Northern Journal is following.

This mining-focused edition, from correspondent Max Graham, includes developments on the proposed Ambler road and neighboring mines, a project to research low-carbon fuel that could come from Alaska mines and challenges to mining projects in British Columbia and the Nome area from Indigenous groups.

—

This edition of Northern Journal is sponsored by The Boardroom, a shared workspace in Anchorage. The Boardroom recently expanded from its original downtown location and opened a gorgeous second space in a convenient Midtown office building — with epic views of the Chugach Mountains. More information here.

Could low-carbon hydrogen fuel come from Alaska mines? Researchers are studying it.

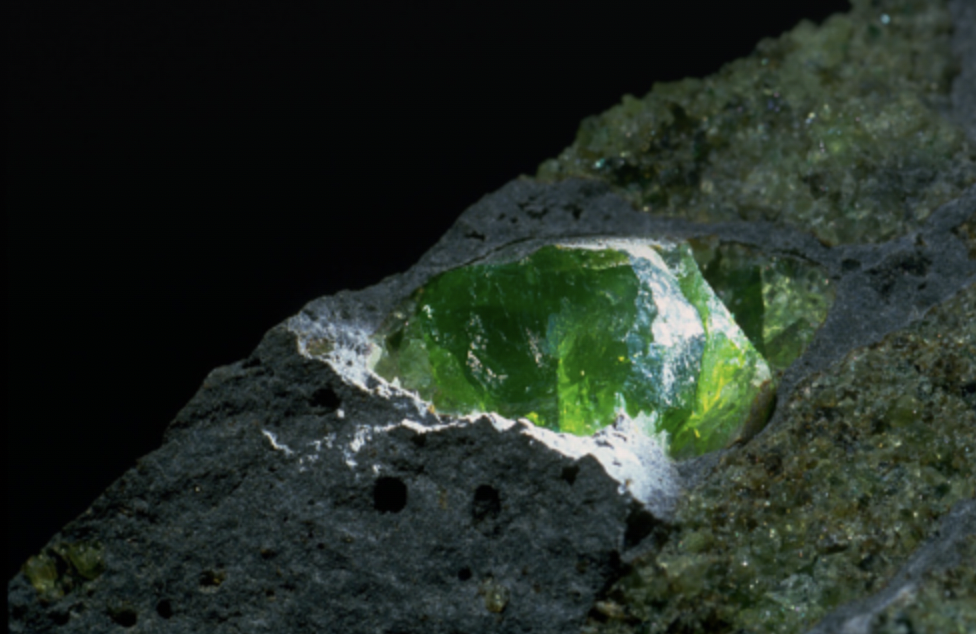

Geologic hydrogen — gas that’s trapped underground or stimulated by injecting water into certain mineral deposits — is all the buzz right now. Boosters say it could revolutionize the global energy system as a potentially abundant source of low-carbon fuel — though it’s not yet proven at a large scale.

What’s gotten less attention amid the hype is how geologic hydrogen could tie into the mining industry. The same rocks that tend to hold valuable deposits of nickel and platinum could also be the source of hydrogen.

That’s why a mineral exploration company recently announced that it would study the potential for geologic hydrogen alongside its search for minerals at two sites in Southeast Alaska.

Vancouver-based Granite Creek Copper, in partnership with Cornell University, is also evaluating potential to sequester carbon pollution at the same sites. The general idea, still in a very early stage, involves drilling into rocks to extract hydrogen, mining those same rocks, then storing carbon in the caverns left behind.

The research is being funded with roughly $225,000 from the U.S. Department of Energy, according to Greeshma Gadikota, an engineering professor at Cornell who’s leading the study.

Granite Creek will send rock samples from its two sites, both near Ketchikan, to Gadikota’s team to analyze their potential for hydrogen development. She said the study also will aim to design a pilot project to test production.

That test project could be designed by the end of next year, Gadikota said in a phone interview last month.

Mining company angling for Ambler Road surges in value after Trump’s election

Donald Trump’s election has boosted a company that’s seeking to build a mine at the end of Alaska’s proposed Ambler road — suggesting that investors expect the new administration to resurrect the stalled development.

Trilogy Metals, which owns half of a joint venture, Ambler Metals, that hopes to develop the Bornite and Arctic deposits on the south side of the Brooks Range, saw its stock price double after Trump’s win.

One share of the company cost 57 cents just before the Nov. 5 election. It was selling at $1.14 on Wednesday — down from $1.35 on Nov. 21, its highest price in more than two years.

“Things are definitely looking a lot better for us than they were about a week or two ago,” Ambler Metals’ managing director, Kaleb Froehlich, said at a Resource Development Council conference in Anchorage last month, shortly after the election. “We do have sort of an opportunity window in Washington, D.C. starting in January.”

It’s a major reversal of fortune for the companies after setbacks during the Biden administration.

Ambler Metals aims to tap into deposits of copper and cobalt near the Northwest Alaska villages of Ambler, Shungnak and Kobuk. The area has long been eyed for mineral development, but it’s remote, and to mine the deposits profitably, an access road is considered crucial.

The road proposal, led by the state of Alaska with support from the mining companies, has been met with fierce opposition from environmental organizations and some Alaska Native groups.

Those opponents include Tanana Chiefs Conference, a consortium of about 40 Interior tribes and villages including some that could be affected by road development. Critics say the road and future mining could threaten caribou, fish and other aspects of Indigenous subsistence culture.

But the project, pushed by the state-owned Alaska Industrial Development and Export Authority, has the support of Alaska’s congressional delegation and some tribal governments in the area. Supporters say development would create rural jobs and stimulate struggling village economies.

Near the end of Trump’s first term, his administration approved a key right-of-way permit for the project, which would cross state, Alaska Native corporation, and federal land, including a 26-mile stretch through Gates of the Arctic National Preserve.

Earlier this year, after a lengthy review, the Bureau of Land Management reversed the 2020 decision, citing threats to the environment and subsistence and harm to Indigenous communities near the road.

Project 2025, a blueprint for an incoming Republican administration written by the Heritage Foundation, a right-wing think tank, calls on the U.S. Department of the Interior to "immediately approve” the Ambler road. (The Interior chapter was written by William Perry Pendley, who served as acting director of the BLM during Trump’s first term. During his campaign, Trump denied connection to the document.)

Froehlich said Ambler Metals has “lots of alternatives” to move the road project forward. Those could include legislation like Republican U.S. Sen. Dan Sullivan’s attempt earlier this year to tack onto a defense spending bill a provision that would rescind the Biden administration’s permit decision.

“All options are on the table right now,” Froehlich said.

Indigenous groups challenge permit decision for massive Canadian mining project upstream of Southeast Alaska

A small Canadian First Nation and an Indigenous group in Alaska each have challenged a British Columbia permit decision for a massive mining project upstream of two Southeast Alaska communities.

The challenges, filed last week in British Columbia’s Supreme Court, call for legal reviews of the provincial government’s decision earlier this year to let a Canadian company hang on, indefinitely, to a key environmental permit.

Seabridge Gold, a Toronto-based company, has been pushing for years to advance what it describes as the largest undeveloped gold project in the world, known as KSM. It would involve a complex of open-pit and underground mines across four mineral deposits buried in the rugged British Columbia mountains in the Unuk and Nass River watersheds.

Both rivers bear salmon, and the Unuk flows southwest into Alaska, near the city of Ketchikan and the Tsimshian community of Metlakatla, where some residents are concerned about environmental and cultural impacts from mining.

The tribally led Southeast Alaska Indigenous Transboundary Commission and a British Columia conservation group, SkeenaWild Conservation Trust, jointly filed one of the challenges. It argues that the provincial government was wrong to deem KSM “substantially started” – a decision that makes the key permit permanent, instead of expiring in 2026.

The Tsetsaut Skii km Lax Ha Nation in northwest B.C. filed a separate challenge saying that the province failed in its legal duty to consult with the First Nation. In its challenge, the First Nation said Seabridge intended to locate its large mine waste site on the nation’s traditional territory and that the province and Seabridge had not meaningfully addressed their concerns.

Seabridge Gold has financial agreements with two other, larger First Nations in the region, the Nisga'a and Tahltan, which formed a partnership last year to participate in the project.

CBC reported a Seabridge executive saying that Tsetsaut Skii km Lax Ha’s rights to the area have not been recognized by the province. The executive said, rather, that the area is recognized as part of Tahltan territory and also is contained in a Nisga’a treaty, according to the report.

The Tsetsaut Skii km Lax Ha cite a 2023 letter from the province with an updated territorial map that encompasses the area in question.

“Seabridge's application for a 'substantially started' determination was widely supported by the communities of northwest British Columbia, including Indigenous communities,” Rudi Fronk, Seabridge’s chief executive, said in a statement. “TSKLH were provided the relevant information early and participated in the province's review process, including submitting comments for the province's consideration.”

Tribal group appeals Clean Water Act permit for contentious gold dredging project near Nome

A western Alaska tribal consortium has appealed a key permit for a proposed gold dredging project in waters near Nome.

Kawerak, a nonprofit that serves some 20 Iñupiaq and Yup’ik tribes in the Bering Strait region, last month asked state regulators for a hearing on a wastewater discharge permit for the project.

The permit, a federal Clean Water Act authorization that’s administered by the state, would allow the Las Vegas-based company behind the project, IPOP, to discharge a limited amount of pollutants into an estuary about 30 miles from Nome, in the scenic Safety Sound area.

In its appeal, Kawerak says the Department of Environmental Conservation, the state agency that issued the permit, “failed to consider the project’s effect on the surrounding Native communities” in its analysis.

The appeal says that IPOP’s development would come “at the direct expense of the Native economy” and that “local Native subsistence and cultural practices will be directly and adversely affected — if not outright destroyed.”

IPOP’s project is opposed by several regional and local groups, including Bering Straits Native Corporation and the City of Nome.

Last spring, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers approved a different permit for the project, reversing an earlier decision to deny it.

Biden administration official visits Canadian mine in Stikine River watershed

A top official at the U.S. Department of the Interior visited a large copper and gold mine in northwest British Columbia recently, where he said he learned more about partnerships between Indigenous nations and mining companies.

Steve Feldgus, principal deputy assistant secretary of land and minerals management, visited the Red Chris mine — a major open-pit operation high in the Stikine River watershed, which crosses the border into the U.S. and flows into the ocean near the Southeast Alaska town of Wrangell.

The mine is located in the traditional territory of the Tahltan Nation, above a Stikine tributary, about 100 miles from the Alaska border.

“The visit highlighted a model for how Indigenous Nations and mining companies can work together as partners, not simply stakeholders,” Feldgus said in a statement shared with Northern Journal.

He added that the visit “helped demonstrate how British Columbia is working to put into action its requirements for obtaining free, prior, and informed consent from First Nations prior to new projects moving forward.”

Feldgus met with the Tahltan Nation Development Corporation, the First Nation’s business arm, according to an Interior Department spokesperson.

The Tahltan and British Columbia governments signed a decision-making agreement related to the mine last year. It gives the Tahltan the authority to reject "substantial changes" to Red Chris operations.

Gold mine near tiny Southeast Alaska town reboots after halting production

Just a few months ago, a Canadian mining company announced that it would halt operations at its newly opened Premier gold mine — just one mile from the Alaska border and about 10 miles upriver from the tiny Southeast Alaska town of Hyder.

This week, Ascot Resources said it has restarted development at the major operation in British Columbia. The news comes after the company raised about $37 million U.S. from lenders and investors this fall.

The mine started producing gold last spring, but Ascot suspended operations within five months because the company wasn’t generating enough ore to feed its mill adequately, owing to construction delays, according to a September press release.

Premier is perched above the Salmon River, a silty, salmon-bearing river that flows past Hyder into an arm of the Inside Passage.