Mine workers ready respirators and go-bags as Red Dog contends with hazardous gas buildup

A recent uptick in sulfur dioxide emissions has fueled health concerns and a public response from the Indigenous-owned corporation that owns the land beneath the mine.

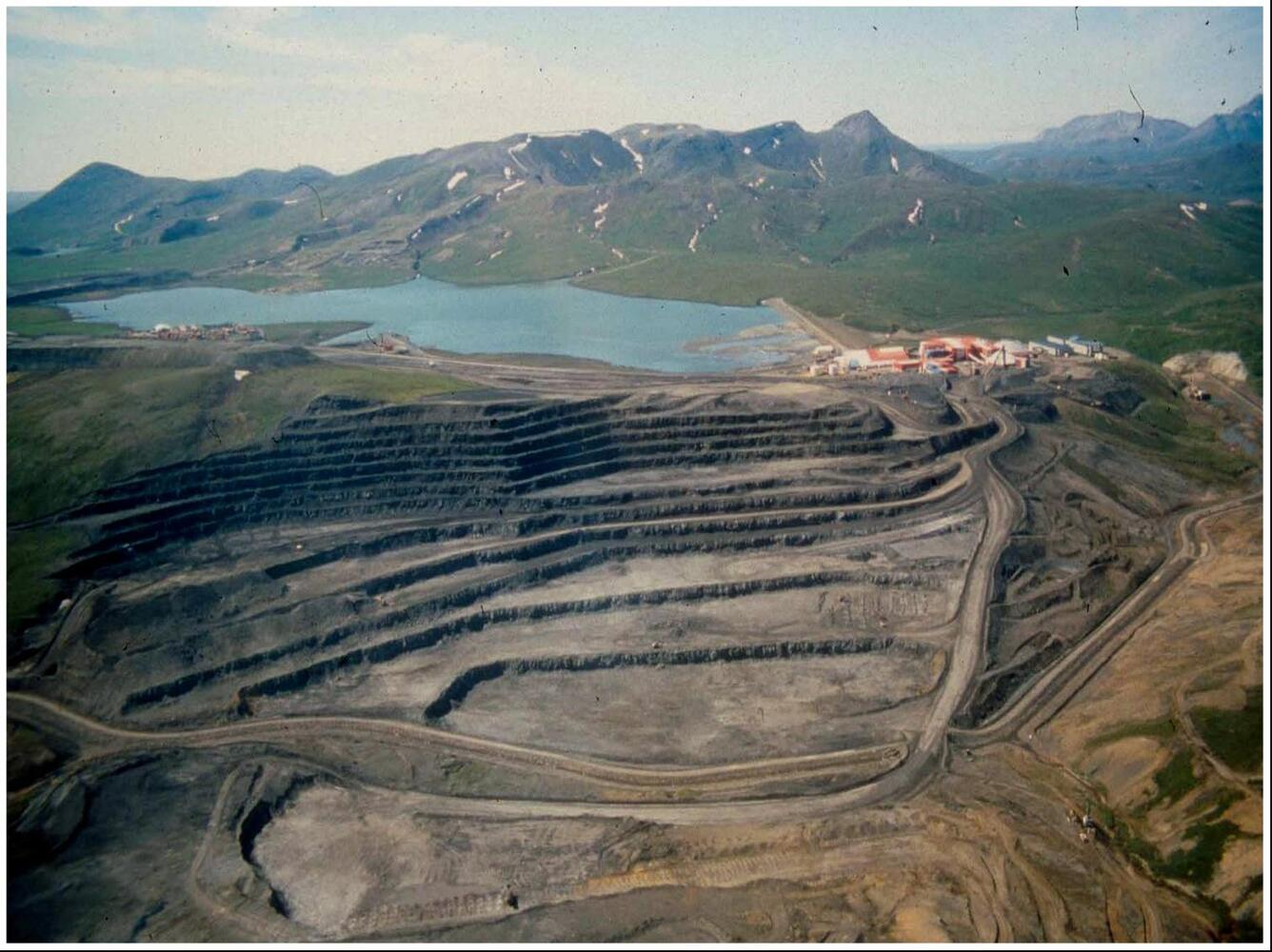

A buildup of hazardous gas at Alaska’s Red Dog mine in recent weeks forced the huge zinc and lead operation to fit workers with respirators and ramp up air monitoring at the mine and in nearby villages.

Since November, reactive ore and waste rock at the remote Northwest Alaska mine has been generating higher-than-usual amounts of sulfur dioxide — a colorless gas that, in high enough concentrations, can cause health problems.

The rock unearthed at Red Dog, one of the world’s largest zinc mines and a major employer in the region, has long generated low levels of sulfur dioxide. The gas, known as SO2, occurs naturally through a chemical reaction when minerals in Red Dog’s ore and waste rock come into contact with air.

But the emissions lately have increased because the mine has been digging up especially reactive rocks — and cold, calm weather has allowed the gas to settle over parts of the sprawling operation.

In recent weeks, sulfur dioxide drifted into mine buildings and reached levels high enough to fuel health concerns among mine employees and officials at the Indigenous-owned corporation that owns the land beneath the operation. Shareholders of the corporation, NANA, make up a significant portion of Red Dog's workforce.

The mine’s operator, Vancouver-based Teck Resources, temporarily evacuated workers from certain areas, limited mineral production and has taken steps to drive emissions back down, according to correspondence obtained by Northern Journal. In the meantime, the company says it’s working to limit the number of workers on site.

“Many of you are concerned and frustrated and have questions regarding our…response to SO2 levels within the buildings,” a Teck supervisor said in a recent email to workers. “The leadership team takes the health and safety of our workforce seriously, including the SO2 challenges being faced.”

Teck has said that sulfur dioxide concentrations at the mine did not exceed federal health and safety standards and that, out of an abundance of caution, it has taken steps to mitigate risks and protect workers.

“Efforts to cool reactive areas and increased wind have resulted in a decline in SO2 levels in recent days,” Teck spokesperson Dale Steeves said in an email this week.

The company, he added, is working closely with federal regulators and NANA to monitor and reduce gas emissions and “ensure continued health and safety of our workforce.”

Teck does not anticipate a material impact on overall production at the mine, Steeves said.

“Red Dog is continuing to operate with appropriate health and safety measures in place,” he said.

The problems at Red Dog have played out under the radar for weeks, even as federal mine safety regulators investigated complaints.

The issue then emerged into public view earlier this month in an unusually blunt statement on social media from NANA, which has long worked closely with Teck. The Native corporation is owned by some 15,000 Indigenous shareholders with ties to Northwest Alaska and receives a share of the mine’s profits.

“NANA is communicating our concerns, and the concerns of shareholders, to the operator and has been taking action within our role as the landowner to ensure those concerns are clearly conveyed and addressed,” the company said.

The statement came a day after Red Dog’s general manager — Teck employee Les Yesnik — sent NANA’s chief executive a memo laying out the situation. NANA then distributed the memo to its shareholders.

Red Dog’s main pit contains rock that’s reactive with oxygen and can “self-heat under certain environmental conditions,” Yesnik said in the memo, which was obtained by Northern Journal.

The chemical reaction between the rock and air naturally emits sulfur dioxide, which in low concentrations can cause irritation to the nose, eyes, throat and lungs and in high concentrations can cause permanent lung damage, Yesnik’s memo said.

Red Dog’s operations have generated the gas since the 1990s, but high iron levels in the ore that’s currently being processed and in the mine’s waste rock have recently created “hot spots” in the pit, Yesnik said.

Low temperatures and low winds have “allowed emissions to settle in lower-lying areas,” where some buildings are located — including where employees sleep and eat, according to the memo.

In response, Teck said, the company has adopted numerous measures to protect workers and reduce the emissions.

It has set up dozens of indoor and outdoor monitoring stations, installed new air filters and has used a water truck to cool the hot spots.

The company also has drafted plans to move reactive rock into a pit filled with water or to bury it beneath less reactive waste.

Teck has reduced production, too, though it needs to maintain some output to avoid damage from an equipment freeze-up in temperatures below minus 20 degrees Fahrenheit, Yesnik said in the memo.

NANA declined to comment.

Sulfur dioxide emissions are a rarely discussed mining problem, but the issue at Red Dog is not unprecedented, said Dave Chambers, president of the Center for Science in Public Participation, a Montana-based nonprofit that analyzes the environmental impacts of mines.

Chambers said he’s heard of similar problems at other mines with deposits rich in sulfide minerals, though he wasn’t aware of an instance when the gas emissions were high enough to cause an air quality problem. Sulfur dioxide emissions are likely much higher from other sources at mines, like diesel generators, than they are from ore or waste rock, Chambers added.

Teck has been sharing SO2 data with regulators at the federal Mine Safety and Health Administration, or MSHA, the company told employees.

That regulatory agency, part of the U.S. Department of Labor, investigated the complaints and concluded "negative findings" for each one, said labor department spokesperson Kristen Knebel.

Knebel did not immediately answer additional questions about MSHA’s actions and would not provide copies of the complaints. Northern Journal submitted a request for those records under the Freedom of Information Act; MSHA estimated the request would take one month to process.

State environmental regulators said they are monitoring the situation but only learned of it through an inquiry from Northern Journal.

Alaska's regulations require companies to notify the Department of Environmental Conservation about releases of hazardous substances.

The department is coordinating with Teck to clarify reporting requirements “since it’s not a routine hazardous substance release, and we don’t encounter this type of situation very often,” Kimberley Maher, a regulator with the agency's spill response program, said in an email to Northern Journal.

Nathaniel Herz contributed reporting.

Public interest reporting like this takes time and money. Northern Journal's primary revenue source is contributions from readers. If you're already a member, thank you. If not, please consider a voluntary subscription by clicking the button above.