Offshore in Cook Inlet, a 'silent economy' hunts for gas to keep Alaska running

Northern Journal helicoptered out to the offshore rig drilling for the increasingly scarce natural gas that powers urban Alaska.

SPARTAN 151 RIG, COOK INLET — Deep below the ocean floor outside Anchorage this spring, a huge drill bit chewed through multi-million-year-old sandstone, sending crushed bits of rock back to the surface through a mile-long hole.

The hunt for natural gas, to keep Alaska warm, had resumed.

Here, on crowded platforms perched above the icy waters of Cook Inlet, a small army labors to keep up the extraction of fossil fuels from Alaska’s oldest producing oil and gas basin. After a half-century of extraction, the gas is still there. But it’s gotten harder and costlier to produce — and fewer companies are participating in the search.

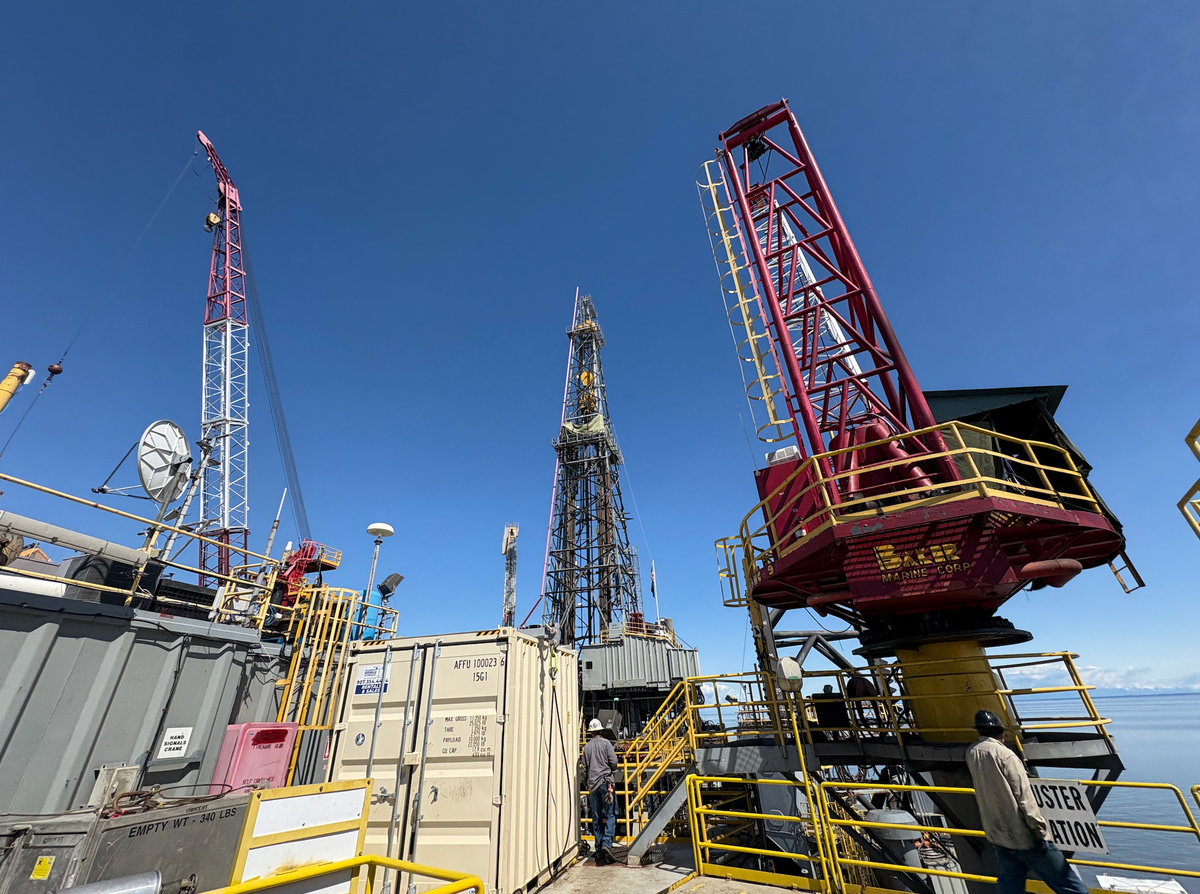

Just one large mobile drilling rig, the Spartan 151, still works offshore in Cook Inlet. This week, its five-dozen workers were hustling to finish two new wells for a small oil and gas firm, Furie.

They’re well-paid and well-fed, with cooks dishing out ample servings of gumbo and fish tacos. On sunny days, they can gaze off the rig at the snow-blanketed volcanoes that ring the Inlet.

But the pressure is on: Urban Alaska’s utilities, some of which have warned of the potential for rolling blackouts amid a gas supply crunch, are counting on Furie’s production.

“I’m scared to death every day,” said Michael Duncan, Furie’s drilling manager. “It’s like, ‘We’ve got to get this.’”

Furie’s drilling effort this year is as close to a glimmer of hope as you’ll find in Cook Inlet these days. But it also underscores the challenges that continue to plague operators there.

Purchased out of bankruptcy five years ago by an Anchorage oil and gas veteran, John Hendrix, Furie is budgeting $38 million to drill its wells this spring — cash that will help keep the Kenai Peninsula’s shrinking oil and gas service industry at work.

But before sinking its drill bit into the seabed, Furie needed help from Alaska’s government. One agency granted it a steep reduction in the 12.5% share of its gas production that the company would otherwise be required to give to the state; another agency approved $50 million in loans.

And earlier this spring, Anchorage’s electric utility and a pipeline company jointly announced a project that could create new competition for Furie: a facility that could receive huge quantities of liquefied natural gas shipped into Alaska from afar. Ironically, the project would convert a Kenai Peninsula facility used during Cook Inlet’s boom days to export excess gas to Asia — repurposing it to handle imports from Canada or the Gulf of Mexico.

Urban Alaska’s electric utilities say that importing LNG appears to be the only way for them to ensure firm supplies of gas for years to come, given the risk, uncertainty and cost that comes with drilling in declining basins like Cook Inlet.

The appeal of a consistent supply of hydrocarbons from global commodities markets is undeniable for locally elected utility boards charged with producing electricity for members at the lowest price. But that argument doesn’t resonate with some of the hardworking hands on the Spartan, and at Furie’s gas handling facility on shore.

Imported LNG “does no good for the state, and now we’re not energy independent any more,” said Furie Operations Superintendent Ben Christianson, 35, who grew up on the Kenai Peninsula and has watched its oil and gas industry shrink as he’s built his career in it.

Producing gas locally, Christianson said, “is good for Alaskans.” Furie employs some 20 people, 90% of whom are residents, according to Hendrix, the owner; the company’s hard hats sport a label: “Home grown energy.”

A declining basin

Furie this week allowed me to visit its offshore platform and witness its spring drilling campaign — which showed how a storied Alaska industry is hanging on in Cook Inlet, while also illustrating the challenge of producing fossil fuels from the increasingly depleted basin.

Production in Cook Inlet began in the 1950s and peaked in the 1970s, when the industry extracted more than 200,000 barrels of oil a day — more than 1% of America’s consumption at the time. Some of the oil was produced from onshore fields, but companies also sunk more than a dozen offshore platforms in the Inlet, which had to be reinforced against huge tides and winter ice floes.

Today, six of those platforms are shuttered, and daily Cook Inlet oil production has fallen below 10,000 barrels, according to state data. Much of the industry’s investment flows instead to Alaska’s North Slope, where companies have discovered huge new fields and are spending billions to develop them.

In Cook Inlet, work is now centered largely on extracting natural gas, which is sold to urban Alaska utilities for power generation and also used by residents and businesses for heating. Vacant, dilapidated buildings line the Kenai Spur Highway, where many of the remaining Cook Inlet oil field supply and service companies have offices and warehouses. The former gas export facility sits shuttered, as does a huge manufacturing plant that once produced fertilizer from natural gas.

“I believe Alaskans have given up on Cook Inlet,” said Hendrix, 67, the Furie owner, who grew up on the Kenai Peninsula and remembers it “just bustling” with oil and gas activity.

All the contracting companies, Hendrix said, “went to the North Slope.”

Interest in Cook Inlet has waned, in part, because of the small size of urban Alaska’s market: Companies say that even if they found a huge new gas field, they wouldn’t have customers to buy up all of their production.

The oil industry’s decline in the Inlet has forced Hendrix into a partnership with a competing firm that now controls the vast majority of the basin’s production: Hilcorp, a privately owned business co-founded by Texas billionaire Jeff Hildebrand.

The helicopter that Furie used this week to get out to its single offshore Cook Inlet platform? Operated by a Hilcorp affiliate, which uses the aircraft to access Hilcorp’s 15 different platforms. The huge dock that, during the winter, hosts the rig Furie is using to drill its wells? Also a Hilcorp property.

The rig itself? It’s owned by Hilcorp, too; Furie is paying hefty sums to rent it, and it has to be returned soon so that Hilcorp can drill wells from its own offshore platforms in the Inlet later this year.

“They’ve made everything available. They’re working with us,” Hendrix said of Hilcorp. “They want us to succeed.”

If Furie’s spring drilling takes longer than expected, though, it could cost the company $2 million to keep the Spartan rig for the additional time, according to Hendrix. That’s in part because the tugboats required to move it are only available on certain days, as they’re also needed in Anchorage to help maneuver the cargo ships that bring in the city’s food supply.

In a prepared statement, Hilcorp said it’s pleased to see the Spartan rig “hard at work in Cook Inlet this summer, supporting efforts to ensure a stable and reliable gas supply” for urban Alaska. The company says it charges Furie the same price to use the rig as Hilcorp charges itself internally.

“We wish Furie great successes as they wrap up their current drilling operations, and we look forward to deploying the Spartan 151 to our own platforms later this summer,” said Hilcorp spokesman Matt Shuckerow.

Tight real estate

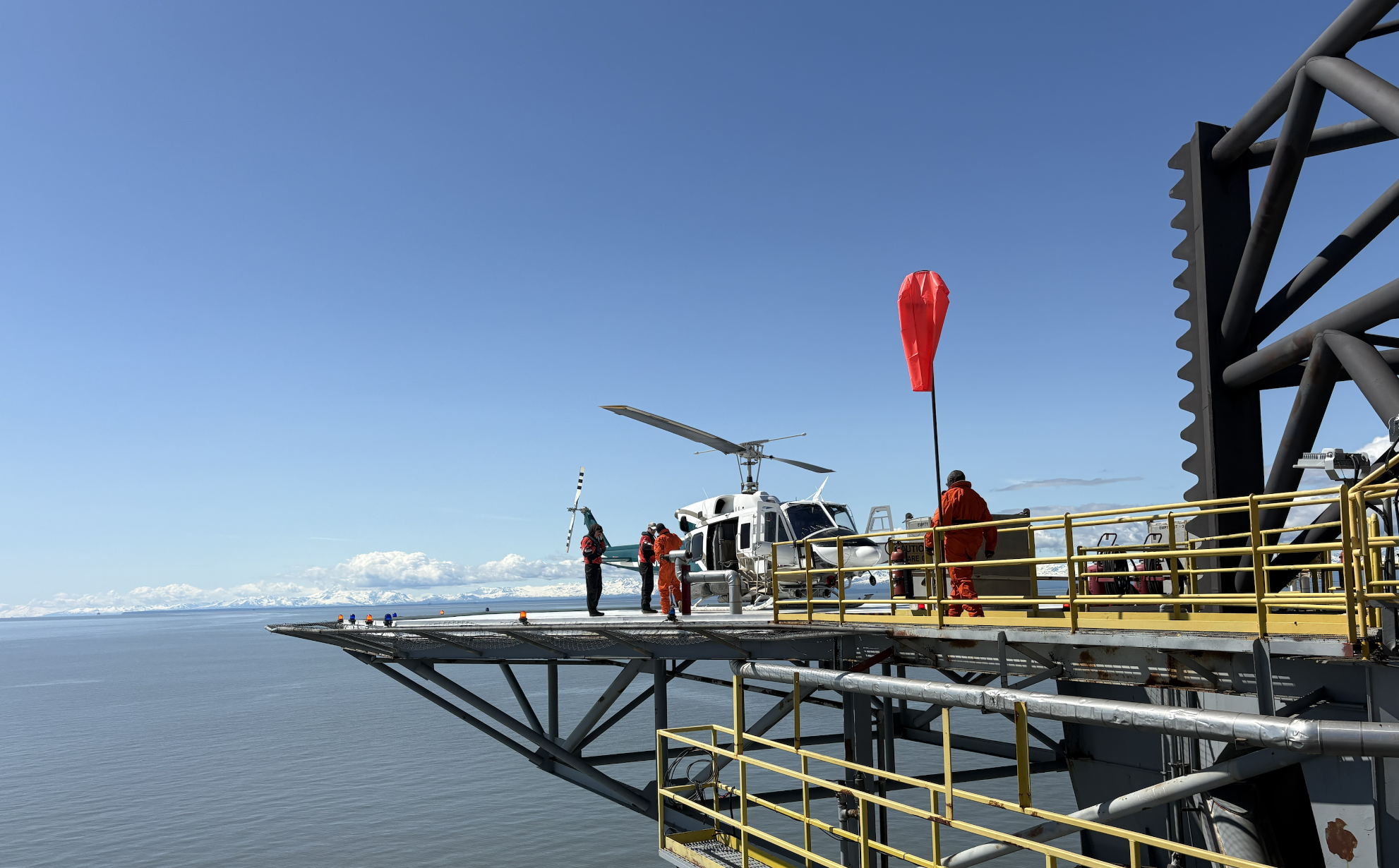

Getting to the Spartan drilling rig is a 12-minute helicopter ride, with all passengers required to don drysuits and lifejackets that could keep them alive in the event of a crash into the water.

Flying out with a Furie official Tuesday were two representatives of their biggest customer, the natural gas utility Enstar, including President John Sims. It was Sims’ first trip offshore, and seeing the huge stacks of pipe and other equipment in such a remote setting made an impression.

“When I walked out and just saw that stuff, it's like ‘holy cow’ — an interruption in operations out there means they're now trying to bring down equipment from the North Slope, which they have to put on a boat,” Sims said a day later. “You appreciate the cost that they have on a daily basis to try to make gas flow to our system.”

Furie’s drilling operation involves two separate pieces of expensive infrastructure that are temporarily linked for the project, each with their own crew.

One is Furie’s gas production platform, the Julius R — a smaller, single-legged structure that’s permanently placed in the Inlet’s waters.

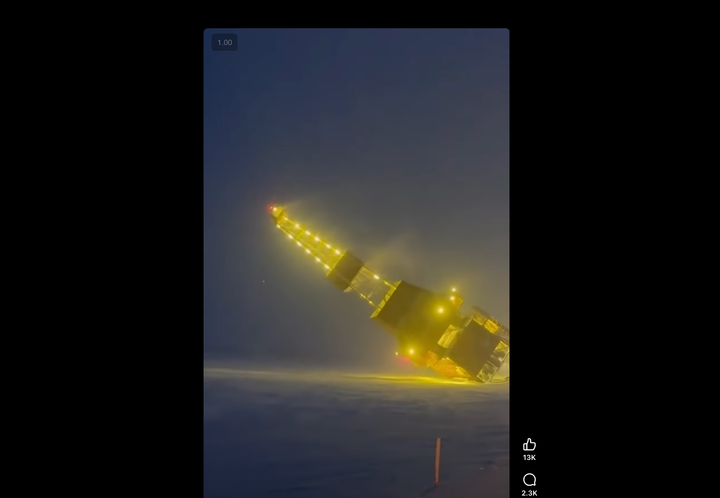

The other is Hilcorp’s hulking, four-legged, Spartan drilling rig, a mobile platform with its own cafeteria and living quarters. Earlier this spring, the Spartan was floated out from a dock and fixed above the Julius R — an intricate operation that involves tugboats pushing it into place.

The helicopter carrying the visitors this week landed gently on a pad extending out over the ocean from the Spartan. Some 60 people, working three-week shifts, staff the rig — dwarfing the handful of Furie employees that staff the Julius R.

The Spartan was originally shipped to Cook Inlet from the Gulf Coast years ago, and it still employs many of the same workers. While some are Alaska residents, it’s rare to find one without a Texas or Louisiana accent.

“These are good people, taking care of each other,” said Duncan, Furie’s drilling manager. “We’re in the middle of the ocean.”

Drilling an oil well from an offshore rig involves representatives from multiple companies, choreographing the movement of enormous quantities of steel on a worksite where space is at a premium. The Spartan’s drill bit descends through its own deck, then passes through slots on the Julius R below before sinking into rock; Duncan says the experts guiding the drill bit could hit your car if you buried it a mile deep and half a mile out.

One of the big challenges on Cook Inlet’s offshore platforms is finding space for new wells. It’s an extremely tight fit for all of the necessary exploration and production infrastructure — not to mention equipment upgrades that could help boost flow rates into the Julius R’s 15-mile pipeline to shore, if only there was room to install them.

“It’s like, ‘You can’t do that — where are you going to put it?’” said Christianson, Furie’s operations superintendent. “There are all these different challenges and struggles that we have with real estate.”

‘You gotta hope’

As of this week, the Spartan had finished drilling to the bottom of its two new wells — the most sensitive and expensive part of the operation. But there were still more steps left before the rig’s job was done, and on Tuesday, mud-spattered workers on the floor of the Spartan helped maneuver lengths of pipe and other equipment.

“We don’t measure in pounds. It’s, really, tons that we’re lifting here in the air,” Duncan said. “It’s a really critical operation — these guys pay very close attention to what’s happening.”

Finishing new wells is a weekslong process; Furie hopes to wrap up and move the Spartan off the Julius R before the end of the month.

But Hendrix, who said he’s invested at least $13 million of his own cash in this year’s drilling program, won’t know if his efforts will pay off until a couple of weeks later. That’s when Furie will blast holes into the sides of the well — a step known as perforation that should, finally, start the natural gas flowing.

“Until we perforate it, we don’t know,” Hendrix said. “You gotta hope.”

The customers who burn the gas from Hendrix’s company will end up paying significantly more than historical prices in Cook Inlet. Enstar, under a new contract recently approved by state regulators, is paying nearly $13 per thousand cubic feet of Furie’s gas.

That’s some 50% higher than the roughly $8 it pays under its contract with Hilcorp — which was inked before the gas shortage arrived.

In past contract negotiations, Enstar pushed suppliers hard “to get the lowest cost with the most reliability for our customers,” said Sims, the company’s president. In retrospect, he added, Enstar may have pushed too hard, negotiating provisions that hurt producers — like Furie under its past, pre-bankruptcy ownership — when they ran into problems and couldn’t deliver promised gas.

“When you think about that risk and that massive expense of drilling — the market's changing, and I think people are becoming more aware that this is dangerous for a company, and we can't put all the risk just on the producer,” Sims said, pointing to the need for the state-sponsored loan to Furie.

In the meantime, the work continues. On the Spartan, crews are staffing round-the-clock shifts to finish up Furie’s wells before moving on to Hilcorp projects.

Hendrix, who once served as an oil and gas advisor to former Gov. Bill Walker, recalled his old boss’ description of the industry as Alaska’s “silent economy” — largely invisible to those who don’t work in it.

“If this was in downtown Anchorage and someone was spending $38 million, everyone would know about it,” he said. “But hopefully, everything will work out, and we'll get our gas.”

Correction: A photo caption originally said the Spartan 151 rig has four legs; it has three.

Northern Journal runs on reader support — voluntary paid memberships make up the majority of our revenue, and will cover the cost of the helicopter ride to the Spartan 151. Join if you can; if you already are a member, thank you.