On rivers and in courtrooms, Alaska battles for land inside national parks and preserves

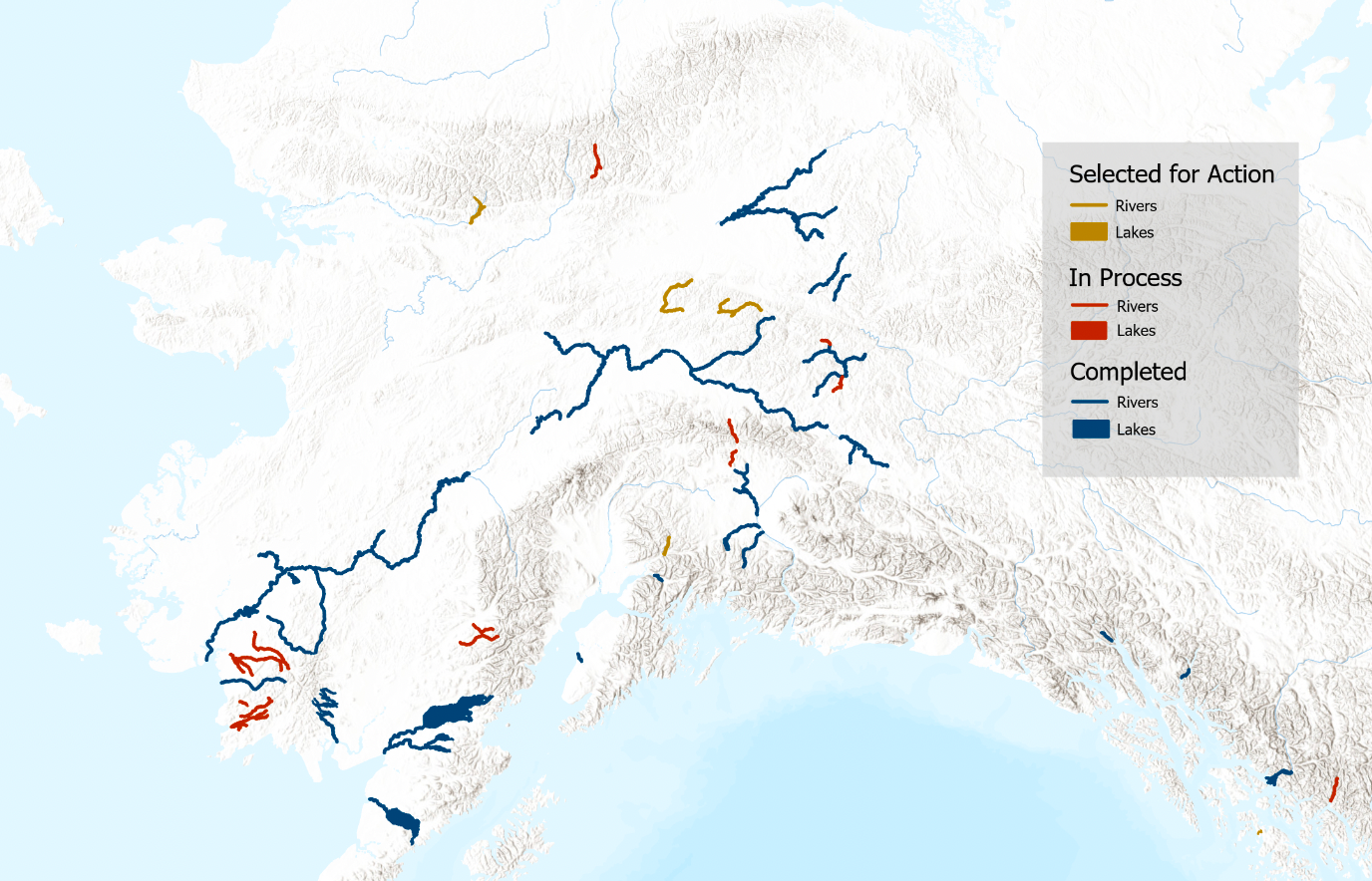

For decades, Alaska land managers have been working to confirm the state's ownership of land beneath navigable rivers and lakes inside national parks and refuges.

LAKE CLARK NATIONAL PARK AND PRESERVE — The two floatplanes circled beneath low clouds before landing on an alpine lake, deep in the mountains west of Anchorage.

They carried employees of the state of Alaska — footsoldiers in a long-running turf war with the federal government.

It was early August, but the high peaks above the lake were already dusted with fresh snow. On a beach at the water’s edge, the passengers climbed out.

They carried guns — but only for bears, not for federal bureaucrats. The lake was deserted.

One of the state workers, Danny Hovancsek, looked down at the sand.

“Welcome to contested land,” he said.

From the two planes, Hovancsek and his colleagues unloaded bags and boxes of gear, including the documentary tools that serve as the real weapons in their war: drones, notebooks, a sophisticated sensor to measure river flow and current.

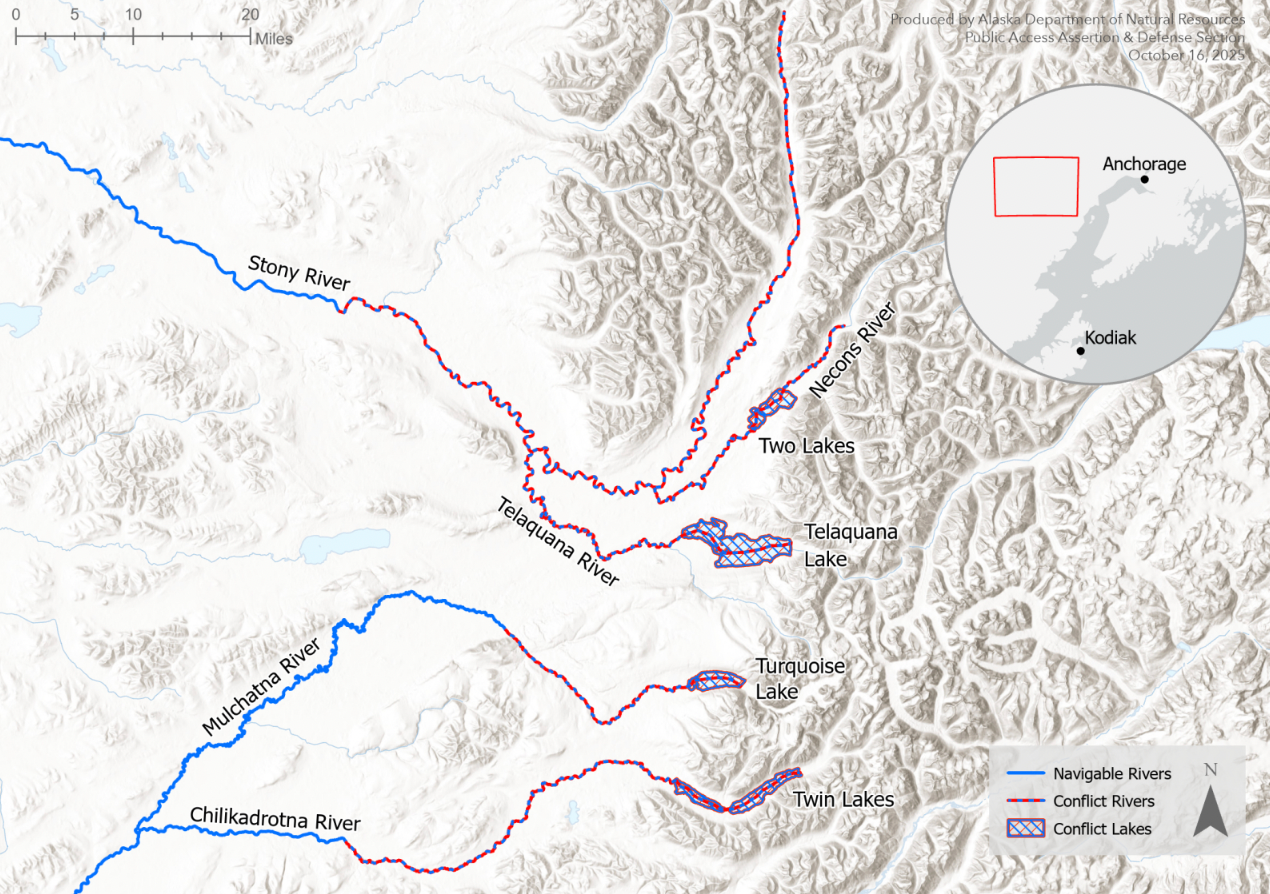

Two Lakes, the body of water they’d flown into, and the Necons River, which drains it, both sit within the boundaries of federally managed Lake Clark National Park and Preserve.

But Hovancsek and his colleagues were there to assert a legal claim to them on behalf of the residents of Alaska, based on precedent that entitles the state to land beneath navigable waters.

The following day, the group would inflate the rafts they’d flown in with and begin floating the river, gathering data they may ultimately need to try to prove the Necons’ navigability to a judge in an Anchorage courtroom.

Other groups from the same state agency, the Department of Natural Resources, had taken similar trips on different rivers in the preceding weeks — part of a renewed, professionalized push to confirm ownership of land within federal parks and preserves that Alaska’s government says became state property at statehood.

The department’s Public Access Assertion and Defense team is a group of roughly a dozen state workers who have, arguably, Alaska’s best public sector jobs. They spend large parts of their summers flying into and floating the state’s remote rivers and lakes, then spend the winters wielding the data they’ve gathered in court.

I was along for the ride. Top department officials — one of whom would sit in a raft along with me — had invited me to observe the state’s efforts, which they say could ultimately help settle the ownership of thousands of miles of Alaska riverbeds, plus millions of acres beneath the surface of lakes.

The work is often done quietly, with the state-sponsored flotillas keeping an intentionally low-profile to avoid giving federal land managers a head start on fighting Alaska’s claims.

But the stakes are substantial, as state and federal regimes can diverge when it comes to managing access and setting rules for boaters, hunters and fishermen, and small-scale miners.

"Anyone who’s looking to paddle a river doesn’t know who to look to for jurisdiction," Hovancsek said.

“I believe in good governance,” he added. “And right now, we don’t know who owns the rivers of Alaska.”

A decades-long fight

At the beach, 130 miles from the national park’s headquarters in Anchorage, there was no indication of federal ownership — no informational kiosks or park rangers.

But the federal government’s resistance to Alaska’s land claims, both through active opposition and simple inaction, was the reason we were all there.

For more than a half-century, Alaska land managers have been fighting successive federal administrations through the courts as well as lengthy administrative processes — battling what they describe as an unwillingness to negotiate from officials of both political parties at the U.S. Department of the Interior, the federal land management agency.

The state has notched numerous wins, including affirming control of land beneath the Stikine River in Southeast Alaska, the Knik River outside Anchorage and multiple forks of the gold-bearing Fortymile River in Alaska’s Interior.

But thousands more miles across dozens of rivers and creeks are still in limbo. And state officials say that in spite of their commitment to the cause, there’s no way each of those stretches will be litigated.

Instead, they aim to file enough lawsuits to make the process painful enough to force the federal government into broader settlement discussions.

“The goal is to sit with them at a table and decide this,” said Jim Walker, the public access team’s chief.

The state’s efforts made little headway during the Biden administration, which clashed often with Alaska officials on resource extraction and land management.

But now, the team sees an opening in Donald Trump’s return to power.

In line with the state’s push, Trump, in an early, Alaska-focused executive order, directed the Interior Department to review the state’s waterways and land ownership.

At a June news conference, the department’s secretary, Doug Burgum, said that as a former governor of North Dakota, he worked on the same issues through the end of his term last year.

“We need to get this thing resolved,” he said. “Even though, right now, there may be differences of opinion, I think we can find some common ground.”

But months later, the Interior Department has not announced any concrete steps to advance negotiations with the state. Alaska’s land-related lawsuits against the federal government remain active. And members of the public access team continue their work in the field.

“Everything starts at zero”

The day after our arrival at Two Lakes, as team members took down tents and washed dishes, one of them passed me a handheld luggage scale and jokingly deputized me as an “agent of state sovereignty.” My task: finding 800 pounds of gear to load into one of the rafts.

Those instructions rested on a century and a half of federal law and jurisprudence that set out legal standards the state must meet to confirm its ownership of what are known as “submerged lands.”

The paper trail starts with the Daniel Ball case — an 1870 U.S. Supreme Court ruling holding that waterways are considered navigable if they can be used as “highways for commerce.”

The Submerged Lands Act, in 1953, solidified states’ ownership of property beneath rivers and lakes that were navigable at the time of statehood.

And a key 1980s federal appeals court case helped establish which types of watercraft could be used to float down an Alaska river — and the amount of weight they should carry — to support a finding of navigability. Hence the 800 pounds.

The public access team can present data they collect on their trips, and records of successful floats, to judges considering the state’s arguments in lawsuits over stretches of particular rivers.

The state can also request that the federal government issue what’s known as a “recordable disclaimer of interest” in submerged lands through a separate, administrative process handled by the Interior Department.

But that process takes five years, on average, to resolve each application — and in some cases it can take more than 10 years, according to federal data. Lawsuits also typically wind through the courts for years.

The glacial bureaucratic processes leave maps of Alaska rife with areas of underwater land where the ownership is in legal limbo — and where the public access team is trying to solidify the state’s title.

Their work is focused largely on the areas, like Lake Clark, that were formally protected by the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980, or ANILCA.

That landmark bill set aside more than one-fourth of the state as federal park or preserve.

But while those areas are now generally understood to be federally managed, ANILCA came after statehood — meaning that land beneath navigable rivers and lakes inside those areas had, legally, already been set aside for the state.

Alaska officials complain that the federal government has long drawn out the process of acknowledging the precise extent of the state’s ownership within national parks and preserves. Federal lawyers, they say, continue to argue over issues that have already been settled by previous decisions, like the size or weight of boats that are used to prove navigability.

“It’s just frustrating to have to argue the same things again and again,” said Ron Opsahl, the state’s main navigability attorney, who floated the Necons with the public access team. “Everything starts at zero.”

Criticism like this has a whiff of the hyperbole that Alaska politicians often employ when complaining about federal bureaucrats.

But in this case, there’s evidence Opsahl is right: In a 2016 navigability ruling frequently cited by state officials, a judge ruled that federal attorneys had acted in “bad faith” by making frivolous legal claims — arguments that had been previously refuted by federal appeals court and U.S. Supreme Court judges.

In conversations with team members on our wilderness trip, I came to see state land managers’ feud with the federal government as something like appealing a claim denied by your health insurance company: counterparts who won’t acknowledge your presence, endless wait times.

“It’s hard to beat an opponent that won’t fight you,” said Hovancsek. He conceded: “In the chess game of landownership, they’re making good moves.”

The public access team had invited me along on the Necons River to show me what one of them described as the “senselessness” of the federal government’s arguments over navigability.

I finished loading the raft and jumped in. As an icy drizzle soaked our raincoats, we turned from the beach toward the lake’s outlet and the start of the river.

“Fighting the big man”

Our group on the Necons was a flotilla of four rafts; I’d loaded up with Walker, who runs the public access office.

Before Walker, the team was led by Scott Ogan, a Republican former state senator from the conservative Mat-Su region; his scouting missions involved more camouflage gear and canned chili than the state’s trips do today.

Walker, an attorney with a silver goatee and an impish sense of humor, looked like he’d be more comfortable in a business suit and a courtroom than in a boat cockpit.

But even as the rain soaked through his gear, Walker was relentlessly cheerful as he pushed on the oars. He described how he sees his work for the state as an extension of his previous career as a defense lawyer in the South, where he sometimes handled death penalty cases.

“When I took this job, people said, ‘You made a career fighting the man. Now, you are the man,’” said Walker. His response: “I’m the little man fighting the big man.”

Walker started with the team in 2014. Soon after, amid a state budget crunch, lawmakers cut the public access team's budget to near-zero.

In the past several years, it’s been largely restored amid a broader effort by GOP Gov. Mike Dunleavy to assert state sovereignty in disputes with the federal government. The team's current budget is some $1.3 million a year, according to figures provided by the Legislative Finance Division.

Without exception, Walker describes his team members as “hard chargers” — the type who, in one case, will spend a vacation bikepacking over snowy mountain passes in Kyrgyzstan rather than lounging on a beach.

Employees are granted ample autonomy and independence, with blocks of time off to make up for long hours in the office and in the field. While scenic, their float trips should not be confused with recreation, according to Tisha Valentine, a team member who was part of the group on the Necons.

“I’m up at 11 o’clock at night, on weekends, doing data collection,” Valentine said. “It’s not all fun and games.”

The team works in a few areas in addition to navigability; one is assembling records of historical trail use that the state can used to assert public access across federal or private land.

On their trips, employees like Valentine get periodic company from attorneys like Opsahl, who want to familiarize themselves with rivers in advance of representing the state in lawsuits over the lands beneath them.

Other top officials at the public access team’s parent agency, the Department of Natural Resources, also tag along occasionally. Brent Goodrum, a deputy department commissioner and retired Marine, is known for his eagerness to contribute to group tasks — or, as colleagues joke, to “storm the beaches.”

A little downstream from Two Lakes’ outlet, Walker nosed our raft to shore, pulling up next to the other boats that had beached there. I stepped into the muck as team members unloaded gear: a waterproof laptop and a duffel bag carrying a tool nicknamed Antonio.

Antonio is a sensor that collects data — stream flow measurements — that the state uses to bolster its navigability claims. It consists of a small, cylindrical device attached to a miniature plastic catamaran that runs back and forth on a cable across the river — meaning that we’d have to fix a line to the far shore some 50 yards away.

I took one end and jumped back in a raft with Jon Fuller, a hydrologist from Arizona who works as a state contractor.

Fuller furiously paddled the boat to the opposite riverbank, where I jumped out and clung to the willows to keep from sliding down the steep bank — suspecting, at least a little, that this was the team’s way of showing me that their raft trips aren’t just sightseeing.

In the meantime, other team members sent up a drone with a camera that they use to document the group’s progress down the river, along with key geographic features. Hovancsek, who was controlling the camera, at one point looked down at his feet, which were planted not on dry land but in a few inches of Necons River water.

Drone operation, he explained, is not allowed in national parks. But it is allowed on state property — which, the state says, includes the submerged land over which the Necons flows, and into which Hovancsek had stepped.

Over the course of our trip, we made several stops like this one, gathering stream flow data and imagery that the state could ultimately cite in a lawsuit.

What are the stakes?

After two days on the Necons, it arrived at its confluence with the Stony River — a broad, pebbly waterway that spills out of the mountains.

The next night, as the chill drizzle finally gave way to high, broken clouds, I found myself standing at the water’s edge, looking at far-off mountain ranges and pondering the fact that I couldn’t say for certain who owned the mud beneath my Xtratuf boots.

That prompted some deeper reflection and conversation about the public access team’s work — and how management of Alaska’s lands might differ under state ownership.

Our route, by that point, had taken us out of the national park. As we crossed the boundary into state territory, Goodrum, the deputy natural resources department commissioner, had asked mischievously: “Don’t you feel freer, Nat?” Walker added his own joke: “There’s a coal mine just behind the willows there.”

In truth, though, little seemed to change. Inside the national park, no rangers had passed by to check our campsites, and permits and entry fees aren’t required for recreational trips.

Given how far the Necons is from roads and other infrastructure, it’s also hard to imagine much industry moving in, even under a more flexible state management regime.

But the Necons is probably an extreme case, where its remoteness means there’s less at stake.

A change in ownership could have larger impacts on busier waterways with contested stretches, such as in the Kobuk and Noatak watersheds in Northwest Alaska.

There, affirmation of state ownership of submerged lands and riverbanks could make for easier access — potentially amplifying conflicts between locals and nonresidents for limited hunting and fishing opportunities.

Two recent high-profile U.S. Supreme Court decisions, in the Sturgeon cases, also created more incentive for the team’s work by confirming the state’s management authority in the areas it owns within national parks and preserves.

That particular ruling allowed a hunter to operate a hovercraft on a navigable river within a preserve in Alaska’s Interior — where National Park Service rangers had previously told the hunter that his hovercraft was banned.

Public access team members and the political officials who oversee them are also quick to argue on principle. Decisions about how to manage Alaska’s navigable waterways, said Walker, “should be made by Alaskans, and not made in Washington by folks who don’t appreciate and haven’t experienced this place.”

“As has been said repeatedly, in U.S. Supreme Court opinions and elsewhere: Alaska is different,” Walker said.

One former high-level federal land manager in Alaska, Pat Pourchot, said he understands that the state has an obligation to confirm its ownership of lands beneath navigable waters.

But, he added, there’s also a reason the federal government should review each claim deliberately: A decision about one river in Alaska, Pourchot argued, could set a precedent for rivers across the country.

“You don’t want to allow a determination of navigability on some really small stream running through a conservation area in Alaska that some other state might push for — say, for the wild and scenic Buffalo River in Arkansas,” said Pourchot, who’s served both as Alaska’s top Interior Department official and as the state natural resources commissioner.

Congressional proposals to address state-federal navigability disputes in Alaska have gotten similarly “bogged down,” Pourchot added.

“Again, you go from Alaska to the nation: How does this apply in West Virginia coal mine country, and how does this apply to other wild and scenic rivers?” said Pourchot, referring to rivers with federal protections.

Pourchot said he also sees state ownership as a possible precursor to expanded mining or oil and gas leasing in ways that conflict with the purpose of national parks and preserves.

But another longtime participant in the state-federal navigability war thinks there’s a tendency on both sides to overstate the stakes of the dispute.

“The feds will say, ‘If the state manages it, they’ll allow coal mining everywhere. They’ll give permits to any outfitter for any reason, for doing anything.’ And that’s just not true,” said Doug Whittaker, an outdoor recreation expert who consults for the public access team.

On the other hand, Whittaker added, state officials say, “‘The feds are going to close everything; you’re never going to get on a river.’”

“That’s not really a thing, either,” Whittaker said. “They’re both exaggerating.”

There are real differences between the two sides, with federal management leaning more restrictive and state management more permissive, Whittaker said. But the reality, he added, is less dramatic than the rhetoric.

Whittaker nonetheless supports the state’s work to settle more of its claims to Alaska riverbeds, saying that ambiguity about landownership can cause real problems.

He pointed to plans the state drafted for the Fortymile River to better regulate small-scale mining operations that posed a risk of fuel spills. That work, he added, advanced only after litigation helped affirm the state’s ownership of the river's gravel bars and banks.

“What I care about is management. And I think both the state and feds can do a good job of managing; they can also do a bad job,” Whittaker said. “I don’t really care who owns it. But I think they should agree on the rules.”

Breaking the logjam

The sun was finally warming us and drying our gear as we pulled the rafts off the water at our take-out point, the confluence of the Stony and Telaquana rivers.

We were early: Float planes wouldn’t be dispatched from Anchorage to retrieve us for another day-and-a-half. And a storm was on its way, according to a weather forecast that Anchorage-based support staff had sent the team through a satellite messaging device.

Walker cheekily suggested that we should gather ark-building material — ”pitch and gopher wood” — for the impending flood. Other team members tried to coordinate an early pickup; their Anchorage flight service, busy with summer tourists, eventually agreed to send a plane.

There was enough room for a few of us, and some of the public access team members needed to get home; the last seat would go either to me or Fuller, the consulting hydrologist. I threw rock, he threw scissors. I would be flying out before the deluge.

As we waited, we discussed our trip down the Necons. After floating its full length from Two Lakes, it was difficult to see how the federal government could plausibly argue that it’s not navigable.

It was deep, with just a couple of riffles in 15 miles. None of the rafts had run aground or even hit bottom, except on a short jaunt down a side channel.

And yet, more than four decades ago, the federal government determined that the Necons is non-navigable, according to the state's public access team, and hasn't changed its position since then. (Federal officials could not be reached for comment about the Necons’ navigability due to the ongoing government shutdown.)

“It’s astounding the federal government is wasting everyone’s money fighting this,” said Fuller.

“If this isn’t fucking navigable,” Opsahl, the state attorney, chimed in, “I don’t know what is.”

The team’s frustration was palpable.

But when I picked up my reporting back in Anchorage, following a presidential election, things had changed.

Walker, in a recent interview, said his team has met with Trump administration officials and presented them with big-picture policy proposals aimed at breaking the navigability logjam. One idea is agreeing on basic principles that would apply to a state application asking the federal government to relinquish an array of riverbeds, rather than just one at a time.

“Instead of going through and giving minute details about every mile of these rivers, we talk, rather, about our methodology and why it’s so sound,” Walker said. “Hopefully, this would begin a dialogue.”

In a prepared statement issued before the shutdown, an Alaska-based spokesperson for the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, Emma Roach, said the agency understands the frustration about the pace of its navigability decisions in the state.

The bureau, which is part of the Interior Department, is excited to pursue improvements in response to Trump’s executive order encouraging progress on the dispute, Roach added.

Evaluating navigability claims “is a complex process — made especially complex in a state as vast, remote, and young as Alaska,” she said.

“But working together on this and other related navigability initiatives, we can make substantial progress,” Roach added. “The state's title to submerged lands at statehood is well recognized, and we’re committed to supporting that process moving forward.”

For now, though, the team’s work continues, with trips this past summer outside Anchorage and up to the Seward Peninsula, on the Alaska side of the Bering Strait.

Some of that work could support new litigation if the state’s talks with the federal government fail. And public access team members acknowledge that there are no guarantees the Trump administration will concede much.

Past Republican administrations have generally been more sympathetic to Alaska leaders’ complaints about federal management. But they've still accomplished little more than Democrats when it comes to resolving the big-picture dispute over Alaska's submerged lands and navigable waters, according to state officials.

“It’s surprising,” said Goodrum, the deputy state natural resources commissioner. “We haven’t made progress on this issue regardless of who’s in office.”

Walker, the public access team chief, said he’s hopeful the recent meetings will produce results. But, he added, “this is not our first rodeo.”

“We’ve heard encouraging words before, which have not translated into results,” he said. “And so very much, in our dealings with the feds right now, we’re trying to put the past behind us — and look forward to constructively and cooperatively getting some of this stuff resolved.”

If you like in-depth journalism like this piece, please consider a paid Northern Journal membership if you don't already have one. This story took months of reporting, and Northern Journal's seat on the bush plane cost more than $1,000.