Outside Olympic glamour, cross-country skiing’s Alaska-based broadcasters face late nights and solo calls

Kikkan Randall is one of the commentators who pulls graveyard shifts over the weekend to call races happening in Europe.

PREDAZZO, ITALY — By day, Andrew Kastning’s life sounds conventional: He’s a father of three, with a desk job in Alaska doing permitting work for a federal agency.

During the winter? It’s another story.

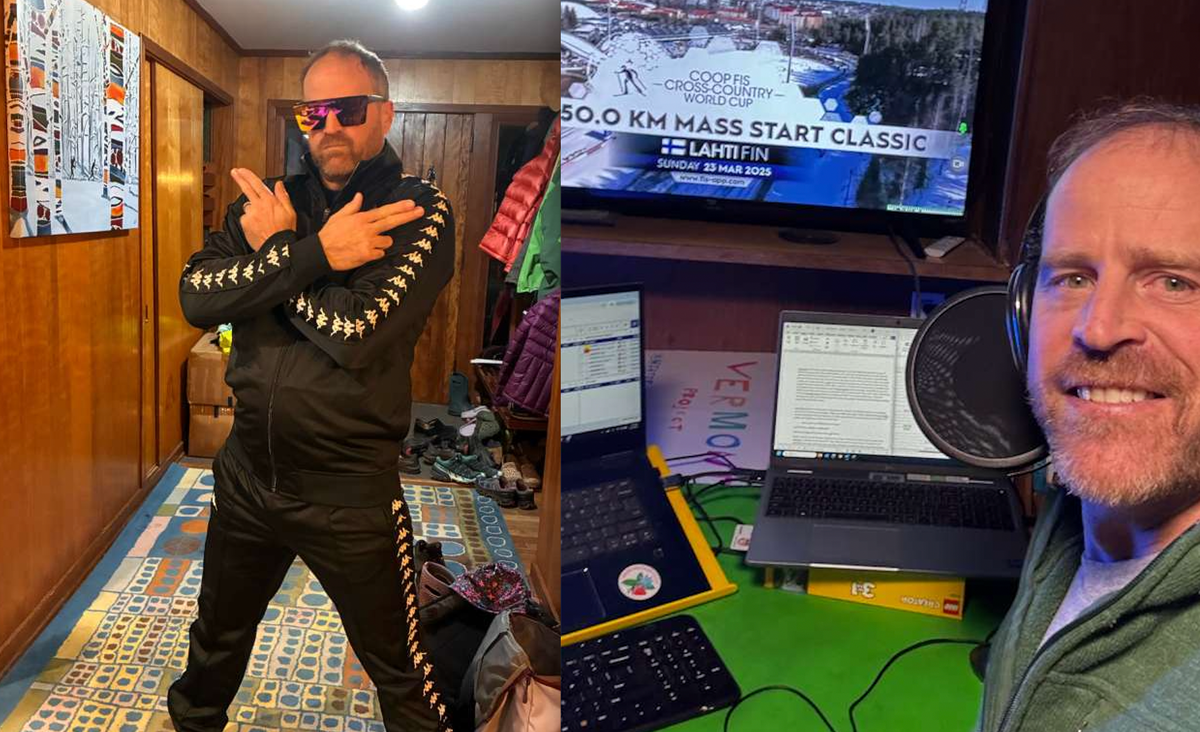

On periodic Friday and Saturday mornings, you’ll find Kastning awake at 1 a.m., 2 a.m. or 3 a.m., standing in his living room in a sports jumpsuit, wearing a headset and delivering a monologue while watching his television.

Welcome to the strange world of being a North American television announcer of Olympic-level cross-country skiing.

With nearly all of the sport’s premier races taking place at European venues, those following cross-country from stateside have to pull overnight shifts to catch the events on an internet livestream.

Kastning, who’s paid by the International Ski Federation to call an English-language broadcast, has outfitted his wife with earplugs and a face mask that plays white noise so she can sleep through his calls. But he still woke his family up with some particularly enthusiastic play-by-play two weeks ago, when a fellow Alaskan, Gus Schumacher, cracked the podium in two World Cup races in Switzerland.

“My oldest daughter said she dreams sometimes and hears me calling the race, like: ‘Jessie Diggins!’” said Kastning, referring to the U.S. Olympic medal-winning skier.

Other regular cross-country broadcasters include Chad Salmela, a former competitive biathlete and veteran analyst from Minnesota, along with Kikkan Randall, the retired Olympic gold medal winning cross-country skier, who lives in Anchorage.

Both Randall and Salmela also pull the weekend wee-hours shifts as regular hosts of the English language livestream. And the pair will be featured this month as commentators on NBC’s national Olympics broadcast — though rather than being on site in Italy, they’ll be working out of an office complex in Connecticut.

Still, the setup will be an improvement over the 2022 COVID Olympics, when the broadcasters were at the same complex but sealed into individual booths connected by plexiglass windows — so they wouldn’t be sharing the same air.

It’s also the first time cross-country skiing will have Olympic commentary from announcers who are working consistently together in the leadup to the Games, with a U.S. Ski Team donor helping to boost Salmela’s and Randall’s pay in recent years to keep them on the livestream for non-Olympic World Cup races.

Cross-country athletes, coaches and boosters say regular television coverage of the sport could ultimately help make the U.S. more competitive with traditional ski powerhouses like Norway and Sweden.

“An underappreciated role of the TV product is how it builds kids' dreams of being future champions,” Randall said in an interview. “This can actually be an important piece of developing our pipeline for the future.”

Randall’s own experience shows how much more accessible cross-country skiing has become for American spectators in recent years. A digital platform, Ski and Snowboard Live, now allows consumers to pay to stream international races while they’re happening or on tape delay.

When Randall, 43, was in high school, she said, “I remember sending in a check via mail to the National Ski Education Foundation to get VHS tapes of the World Cups of the year before.”

“Outside the Olympics, that was the only way to see World Cup level skiing,” she said. It was “pretty much completely inaccessible,” she added.

Randall has now fully embraced her role translating cross-country skiing’s sometimes-complicated race formats to a mass audience.

“I was curious: Am I going to know what to say? It's one thing to have lived it, and it's another to be able to talk about it,” she said. “But it's come to me more naturally than I thought it would, and I really enjoy it. I get, kind of, a thrill from it — and it makes me happy to still feel that connection to the sport.”

With two kids and a full-time job leading Anchorage’s ski association on top of the commentary gig, Randall said she has to weigh opportunities carefully. It’s helped that the ski team donor, a strategic consultant named Liz Arky, offered to bump up the pay rate for the core broadcast team of Randall and Salmela — who now earn more than the few hundred dollars a night Kastning gets when he fills in.

“They can hook you, because they’re such good storytellers, and they’re so immersed in it, and they’re so passionate about it — and I just feel like that’s infectious,” Arky said in an interview. “It’s incumbent on us to grow our community and grow the audience.”

Salmela, meanwhile, pulls double duty as a commentator for both biathlon and cross-country races that are nearly all in Europe. The repeated early morning wakeups are a grind, and Salmela said his doctor has questioned whether it’s worth the cost.

“It’s a hard existence for a guy who’s 54 and dealing with Parkinson’s,” Salmela said. “It’s a tough call, because I recognize that it’s important for the sport.”

Salmela’s looking forward to the Olympic broadcasts on NBC, though, as they offer the commentators substantially more support than they get for the World Cups during the rest of the season: statistics researchers, a producer, a sound assistant. Salmela also said he’s enjoyed the partnership with Randall, who he called a “natural analyst.”

“Her content is superb,” he said. “Because she’s smart, and she’s been one of the best at the sport — so, her perspective is well-spoken and legitimate.”

Kastning’s job can be tougher: He’s a solo practitioner for all his broadcasts, with no other analysts to banter with or riff on his takes.

He spends lunch breaks in the days before the races looking for storylines and fiddling with an Excel statistics spreadsheet. He’ll try to nap a bit in advance, then wakes up, closes his sleeping kids’ bedroom doors and heads into the living room for a sound check that takes place an hour before the start.

The toughest nights are when he’s calling two separate races, one for men and one for women: There’s generally an hour, sometimes two, between them.

“It’s really tempting to take a nap in between, because we’re talking like 2 to 3 a.m.-ish,” he said.

Kastning draws energy, he said, from his jumpsuit, which was donated by Alaska Olympic cross-country skier JC Schoonmaker.

After the soundcheck, Kastning said, “I’m kind of waiting until 10 minutes out — the countdown begins.”

“And then I’m off and running,” he said.