Letter from Yakutat: Deep cuts on the Lost Coast

Logging is on the decline across Southeast Alaska. But in Yakutat, the local Indigenous-owned corporation is still cutting, over the objections of tribal and cultural leaders. Here's a firsthand look.

This edition of Northern Journal is sponsored by The Boardroom, a shared workspace in Anchorage. I use their array of comfy and light-filled spaces as an alternative to my home office, and I also enjoy the free kombucha and convenient access to downtown. Check out membership options here.

A note to readers: I paid all the costs of my reporting trip to Yakutat, which cost close to $1,000. If you support stories and work like this, please consider a voluntary paid Northern Journal subscription, which costs $100 a year or $10 a month. If you already have one, perhaps suggest to a friend that they subscribe, or you can purchase them a gift subscription.

Centuries ago, a few dozen Alaska Natives left their home on an epic migration.

They were of Ahtna descent, and their trip began in Alaska’s Interior, in the Copper River watershed. They passed through some of the most rugged terrain in the world, and for a period of years, the group lived in the vicinity of the massive Bagley Icefield, using snowshoes to stay on the surface. One boy still died along the way, according to oral tradition, when he fell into a crevasse and couldn’t be rescued.

The 200-mile journey ended near the present day community of Yakutat, along Alaska’s thinly settled Lost Coast between Anchorage and Juneau. There, they exchanged copper with another Indigenous group for the rights to a salmon stream — Kwáashk' Héeni, or Humpback Creek — along with an island to settle on, and a large swath of the surrounding Yakutat Bay.

The clan ultimately renamed themselves for the creek, and the Kwáashk'ikwáan settled in the Yakutat area.

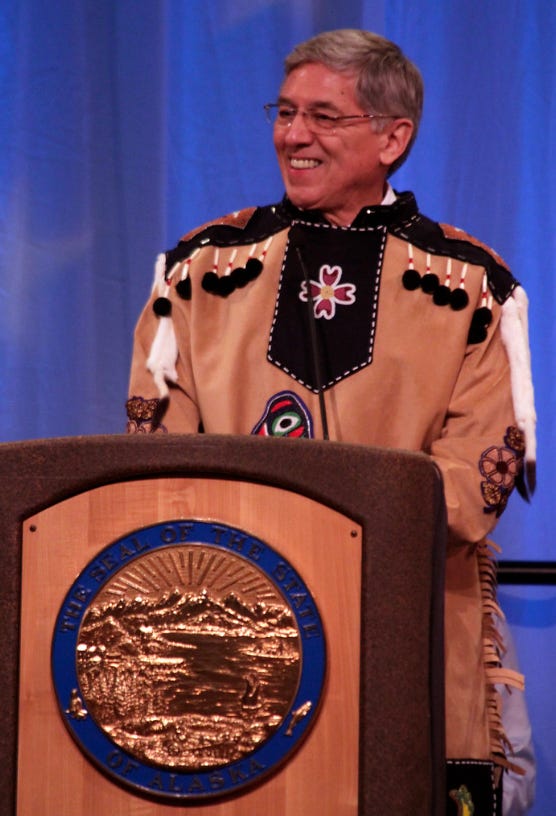

Over time, they mixed with the Indigenous Eyak and Tlingit people who also now call the place home. Kwáashk'ikwáan people still live in the Yakutat area today, and the clan has produced prominent Tlingit leaders, including Byron Mallott, the former Alaska lieutenant governor.

The creek, meanwhile, became a sacred possession of the Kwaashk’ikwáan clan. Which is why a modern day furor erupted when Yakutat’s Indigenous-owned village corporation — led by Kwaashk’ikwáan members — began a timber harvest at Humpback Creek.

The ensuing controversy has divided the town and caused deep rifts between its people. And it’s underscored how Alaska’s unique Native-led institutions charged with bettering the lives of Indigenous residents — tribal governments and for-profit, land-owning corporations — can have sharply diverging visions of the way forward.

The Kwaan

I’d been hearing and reading about Yakutat’s logging controversy for two years before I finally decided to buy a plane ticket to town last month.

The Alaska Airlines jet landed at dusk, and I spent the evening at a raucous high school boys basketball game, where the Yakutat Eagles hung tough with a scrappy team from Skagway before fading in the second half.

The next morning, I woke to find that my bed and breakfast was perched above the bright green waters of Monti Bay, and I drove along the shoreline in my rented SUV to the modest offices of Yak-Tat Kwaan, the village corporation.

Shari Jensen, the chief executive, met me outside and showed me into her office, lined with maps, to talk about the corporation she leads.

The Kwaan, as it’s known, was established in 1973 after passage of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act. That legislation, approved by Congress and signed by President Richard Nixon, extinguished Indigenous Alaskans’ land rights in exchange for nearly $1 billion and some 10% of the acreage in the state.

The land was transferred to more than 200 newly established Native corporations, which were charged with using their property to benefit the Indigenous Alaskans who were awarded shares in the businesses.

The corporations are separate and distinct from federally recognized tribal governments, which run programs supporting the same Alaska Native people but have no automatic legal rights to use or access the corporate land.

Yak-Tat Kwaan was entitled to 23,000 acres, or 36 square miles — a tiny fraction of the traditional homelands of Yakutat’s Native people.

Those 36 square miles, however, did contain a valuable resource: trees. Even after the corporation logged some of its lands in the 1980s and 1990s, as part of a partnership called Koncor Forest Products, a 2001 survey of just one-fourth of the Kwaan’s property estimated its remaining timber value at $35 million.

Today, the Kwaan is led by a nine-member board elected from, and by, its Indigenous shareholders.

Before launching its current logging business, the corporation had made other investments, including in information technology and a costly fish processing plant. But those didn’t bring in the kind of money that some board members thought could come from the timber industry.

Jensen, the chief executive, told me she wants the corporation to diversify into ecotourism.

Visitors already flood into fishing lodges near Yakutat during the summer. And Jensen said that the Kwaan owns some prime waterfront property that, if trees are cleared and cabins are built, could host surfers, hikers and sightseers.

But the Kwaan lacked the capital needed to launch such a business, which is why board members looked to timber, according to Jensen. Cutting trees was a way to create jobs, generate profits and pay for heavy logging machinery that the corporation could also use to build housing and tourism infrastructure, Jensen said.

“See this, right here, that we own? This is nothing but beach, all the way around,” Jensen said, gesturing at a map of the Kwaan’s land holdings. To clear the land, she said, the corporation needed a timber business.

The Kwaan’s board also discussed the option of selling carbon credits on its forested lands — an arrangement where polluters pay timber owners to leave trees standing.

Other Southeast Alaska Native corporations, like Juneau-based Sealaska, have generated substantial revenue from carbon credits and are moving to exit the timber industry. But the Kwaan didn’t pursue the idea.

Jensen said carbon credits revenues would have trickled in too slowly, and that such deals wouldn’t have created local jobs. So, in 2018, the Kwaan launched a subsidiary, Yak Timber.

Borrowing for start-up costs

To acquire logging equipment and pay start-up costs, Yak Timber borrowed millions of dollars. Documents filed with state agencies in June show more than $10 million in loans that haven’t come due, and the company has pledged its logging equipment and timber rights as collateral to its bank, Northwest Farm Credit Services.

The Kwaan could have limited the borrowing by teaming up with an investor or an established logging business. But in interviews, board members said they were skeptical of bringing in outsiders because of the corporation’s experience with Koncor Forest Products in the 1980s and 1990s.

Koncor, with the Kwaan as a partner, harvested much of the Yakutat area’s prime timber. But the deal left some Kwaan shareholders feeling burned. Marvin Adams, a current Kwaan board member, argued that Koncor’s other partners got an unfair portion of the profits.

“Our position today is to go back in and take what we have left,” said Adams, referring to the current timber harvest. “Because we missed that boat.”

Yak Timber’s initial business plan, drafted by Adams, called for logging to start in an area that was previously cut in the 1950s: a corporate-owned parcel next to the town dump. The first shipment of logs, to China, left Yakutat in late 2019.

The hemlock and spruce harvest, and subsequent cutting on other Kwaan lands, created 26 local jobs, and for two-and-a-half years, there was no public outcry, Adams said. But when Yak Timber couldn’t convince the state and the U.S. Forest Service to open up public land for timber harvests, it started looking at more sensitive corporate-owned areas to cut — and opposition began to stir.

In mid-2021, Yakutat’s local government — led by Mayor Cindy Bremner, a former Kwaan board member and chief executive — lodged objections with state regulators about a proposed cut that it feared would irreparably damage salmon habitat in the area of a local stream, Ophir Creek.

A subsequent plan called for selective harvesting of trees on Khantaak, a barrier island just north of town. But Khantaak is a popular recreation and subsistence area for Yakutat residents and, amid a broad backlash, Yak Timber abandoned the idea.

Many of the Kwaan’s critics told me they’re not opposed to all logging — just harvests that threaten areas they value for subsistence, recreation and the potential they could hold cultural or archaeological relics.

"I am not against logging when logging is done properly," said Marry Knutson, who works for Yakutat's tribal government. "My only motive is to protect our culture."

The opposition has left Yak Timber with limited options to continue cutting trees, and to satisfy the bank that financed the timber operation, Jensen, the Kwaan’s chief executive, told me.

She said the collateral used to get the loan — namely, the logging machinery — is at stake: “We’re trying to do everything we can to hang on to the equipment,” she said.

The financial pressure to repay the loans has escalated, however, in the past few months, after shareholders rejected logging on the barrier island, Jensen said.

“They were satisfied with what we would have gotten off Khantaak, thinning the trees,” she said. “But now we’re going to have to come up with another option.”

Meanwhile, over the objections of tribal and cultural leaders, Yak Timber had been logging at Humpback Creek — the salmon stream acquired by the Kwáashk'ikwáan clan centuries ago.

Kwaan board members had downplayed the historic and cultural significance of the Humpback Creek site. But in early December, an anonymously-run social media account, Defend Yakutat, posted a photo that it said was taken there by a Yak Timber employee.

It showed a previously undiscovered stone wall.

In an announcement shortly afterward, an archaeological expert said the discovery could reveal a "unique record of traditional lifeways and subsistence practices extending back 700 years."

The people of the Humpback Creek

I’d never been to Yakutat and knew little about its Native people, so before I flew there, I pored over a 350-page National Park Service ethnography that was recommended by one of my contacts in the village.

The document laid out a rich Indigenous history, describing the Yakutat area as a regional melting pot.

The Eyak were the area’s first residents, who arrived after traveling down the coast from the north as the Hubbard Glacier retreated out of Yakutat Bay. Then, the Tlingit came from the south and largely absorbed the Eyak into their culture.

That history is reflected in the community’s name. Yaakwdáat, “the place where canoes rest,” is Tlingit, but it’s derived from an Eyak word, Diya’quda’t.

The Kwáashk'ikwáan come from a third Indigenous group, the Ahtna.

In the region’s oral traditions, there are several iterations of the clan’s migration saga, which was first documented in 1904.

But all the versions agree that the clan’s members, upon arriving in the Yakutat area long ago, clashed with some of the existing residents over subsistence resources, including Humpback Creek. The conflict was resolved through an exchange of tináa, or copper shields, and the clan ultimately adopted the humpback salmon as its crest, or sacred icon.

The creek itself also became an at.óow, or sacred possession, according to the Park Service ethnography. Kwáashk'ikwáan territory eventually came to stretch more than 70 resource-rich miles along the Lost Coast, making it one of the region’s most economically powerful clans.

Yakutat residents told me that the logging at Humpback Creek was an essential part of the town’s feud over Yak Timber. And so, after leaving Jensen’s office, I went in search of the Kwáashk’ikwáan leadership.

To find it, I climbed a set of wooden stairs to a well-appointed dwelling directly above one of the town’s two supermarkets: Mallott’s General Store, established in 1946.

The Mallotts are one of Southeast Alaska’s most prominent Indigenous families. An 82-year-old white man and a shaggy dog greeted me at the door.

Larry Powell first met Caroline Mallott when he was a crab fisherman in the area up from Washington, and the couple later married. They’ve run the store since the 1960s, when they bought it from Caroline’s mother.

One of Caroline’s brothers, Byron, was the head of the Kwáashk’ikwáan until his sudden death in 2020, at age 77. That left Caroline as the clan’s matriarch, but she’s suffered from health problems and wasn’t able to speak with me.

Byron Mallott’s successor as clan leader is expected to be announced at a ceremonial potlatch. But because of the pandemic, the potlatch hasn’t been held yet, nearly three years after his death.

That meant that his clan’s leadership was still in transition when word started spreading about Yak Timber’s plans to log the namesake creek of the Kwáashk’ikwáan.

Byron Mallott was a magnetic public speaker who served as Alaska’s lieutenant governor between 2014 and 2018, and he held an array of government and Native leadership positions before that. One Yakutat resident told me she thought that if Mallott had still been alive, he “never would have let this happen.”

Sitting with me at his living room table, Powell was skeptical of that argument, saying it’s not clear that Byron Mallott’s advocacy would have made a difference. Yak Timber, Powell said, has continued logging at Humpback Creek even after Caroline Mallott worked with two different tribal governments to lodge their objections.

“They kept saying they’re not going to do it right up until, practically, they started,” Powell said. “By that time, they weren’t listening to anybody.”

The harvest

Since Yak Timber began cutting near Humpback Creek, a caustic fight has erupted in Yakutat over the site’s significance.

Opponents point to the creek’s symbolic value to the Kwáashk’ikwáan clan, and say that the absence of previous archaeological discoveries is far from proof that there’s no evidence to be found.

“Technology has changed over time,” said Knutson, the Yakutat tribal government employee. “And that’s why the exploration of this area, by archaeologists, is important.”

The most aggressive defender of the Humpback Creek harvest is Adams, the Kwaan board member and head of Yak Timber.

During my trip to Yakutat, I’d watched a video released by Yak Timber that features Adams, in a button down shirt and vest, introducing himself as both the company’s chief executive and the leader of one of the houses within the Kwáashk’ikwáan clan.

In the video, Adams summarizes the findings of a famed anthropologist, Frederica de Laguna. De Laguna spent years in the 1940s and 1950s compiling a three-volume cultural history of Yakutat published by the Smithsonian Institution, and she worked with dozens of residents.

Her research describes Yakutat’s clan houses and settlements, and covers the oral history of Humpback Creek’s acquisition as a fishing stream by the Kwáashk’ikwáan. But it includes only a passing reference to seasonal settlement there — by the Eyak, the Indigenous group that preceded the arrival of the Kwáashk’ikwáan.

“It’s incomprehensible for me to understand that, if there was a settlement in the Humpy Creek, why was it not listed in this comprehensive study?” Adams said in the video.

Adams also cited U.S. Forest Service research, including a 1975 report that he said documented no depressions or other indications of settlements. And he invoked the words of his grandmother.

“What she said was that, ‘yeah, the Kwáashk’ikwáan, which was our clan, purchased the area,’” he said. “But it was mostly for the hunting and fishing rights, not for the settlements.”

Knutson, when I interviewed her, said the tribal government bears some responsibility for the lack of modern research in the Humpback Creek area, which could have been funded by grants. But its resources are limited, she added, and the tribe has prioritized efforts like developing housing in Yakutat’s tight market.

“We have to take care of our people that are living right now in order to take care of our ancestors,” she said.

The tensions over logging at Humpback Creek reached new levels in December, with the anonymous Defend Yakutat account’s publication of the rock wall photo.

A week later, Yakutat’s tribal government, along with Sealaska and its cultural arm, Sealaska Heritage Institute, issued a statement calling on Yak Timber to stop logging in the area. The groups cited Defend Yakutat’s report of “several house pits and a series of parallel stone walls laid across a dry creek bed.”

The stone wall is “clearly a cultural feature” that was probably part of an Eyak settlement in the area, said Aron Crowell, an anthropologist with the Smithsonian Institution’s Arctic Studies Center who’s worked at several sites near Yakutat and collaborated with the tribal government.

The likely reason the evidence was only just discovered, he added, was that it was hidden in trees.

“From my own experience, and many others’, it's not that easy to find sites in a forest,” Crowell told me. “I think in the end, it will prove to be one of the most important archaeological sites in that area.”

“Small-town politics”

The dispute over logging in Yakutat has caused sharp rifts in the village of 600 people. Residents described fights within families, awkward encounters at the grocery store and relentless criticism of the loggers still working for Yak Timber.

Amid those tensions, Defend Yakutat has taken extraordinary steps to preserve its own and its sources’ anonymity. It’s used distortion technology to disguise voices in its audio recordings, and one recent video showed a hoodie-clad subject dimly lit from behind to obscure their identity.

“You know how it goes: Small-town politics,” Defend Yakutat’s operator said in a prepared statement sent by their Anchorage attorney, Jim Davis. “Anonymity does not change the facts. It does not change that a potential village or fishing site has been discovered because of the logging many community members and Alaska at large did not want.”

Adams, the timber company’s chief executive, has been the focus of Defend Yakutat’s criticism.

As tensions escalated in the village, flyers started showing up on bulletin boards around town. They depicted the same image of Adams’ head repeatedly photoshopped atop stumps at a clear cut site, with a caption: “Who benefits from commercial logging in Yakutat?”

The Kwaan’s most recent financial information shows that the corporation paid Adams $194,000 in 2020 for his work as Yak Timber’s chief executive. (Adams said his salary that year was $167,000 and that the difference was based on per diem and travel.)

At the same time, in an interview in Yakutat, Adams’ former office manager, Jennethan Kaufman, told me she and her husband once loaned the company $18,000 for four days so that it could make payroll.

A consultant for Yak Timber has also filed liens against the company for overdue payments. A Washington state boatyard manager has complained to tribal and corporate officials about non-payment by Yak Timber, according to an email I obtained. And a federal lawsuit is playing out over a barging contract between Yak Timber and an Alaska Native-owned environmental consulting firm.

One of the ways that Adams has responded to the criticism is by filing a libel lawsuit against Powell and two other critics, along with John and Jane Does. His complaint said the defendants made false allegations about his involvement with Yak Timber, and he’s seeking more than $100,000 in damages.

But even one of Adams’ allies in Yakutat has acknowledged concerns with his leadership. Jensen — Adams’ sister and the Kwaan’s chief executive — shared with a dissident shareholder, who subsequently published the messages, her anxiety about the way her brother and another board member were leading the timber subsidiary.

The two leaders, Jensen wrote, “are in total control and they’re spending like there’s no tomorrow. Anyone who gets in their way is being booted out.” She added: “I am desperate to stop them before they inflict too much damage on the corporation.”

Jensen, in her office, told me her concerns were shared confidentially with the dissident shareholder, and that they were more about leadership style than they were about the direction of Yak Timber. And she said that while Adams can be hard to work with, with a “domineering personality,” those qualities are assets in the business realm.

“He fits in the majority of CEOs’ personality. He would get a top job if he left here,” she told me. “They have to be in control. They do it all. But they make it happen.”

Adams met me at a coffee shop in Anchorage, where he lives. He said he’d been misquoted by other journalists, and asked to record our conversation.

He initially declined to speak in specifics about the company’s finances.

In a follow-up phone conversation, he said Yak Timber was disputing the claims about unpaid bills by the Washington boatyard. But he acknowledged that Kaufman made the payroll loan early in the company’s formation, and said Yak Timber is working out a payment plan with the timber consultant who filed the liens.

“It’s environmental pressure that’s disrupted the continuity of the harvest and created these financial issues,” he said. “When you sit there and have all your inventory pulled out from underneath you, that becomes a challenge.”

But Adams was vehement in his defense of the harvest at Humpback Creek, and he made a point that seemed significant: One side of the creek was logged decades before, during the Kwaan’s partnership with Koncor — an era when some of Adams’ critics served on the Kwaan’s board.

“These are the same people that benefited from 11,000 acres of harvesting,” Adams said. His critics, he added, “said that we were desecrating grave sites. That’s their words, they put in resolutions on it. And it’s a lie.”

When I asked Larry Powell about the logging history at Humpback Creek, he said shareholders rebelled when Koncor’s operation approached the area. And the logging company ultimately agreed to stop cutting there in response to pleas from Kwaan board members, Powell said.

“They didn’t want them going any farther around Humpy Creek because they knew the cultural significance of it,” he said. “The people said, ‘No more.’ And they listened.”

A tree’s value

At the end of my conversation with Adams, I asked another burning question that I’d heard from a number of shareholders: Why lead his Native corporation into the timber industry when logging is on the decline nearly everywhere else in Southeast Alaska?

It seems like there are too many systemic forces arrayed against Yak Timber for it to succeed, I said to him.

Executives at other Native corporations say that younger shareholders seem to value cultural preservation over logging, mining and whatever else constitutes “resource development.” The U.S. Forest Service, through the Roadless Rule, limits logging on federal holdings. And Southeast landowners are increasingly getting paid for carbon credits — leaving trees standing rather than cutting them down.

“I think if you’re an environmentalist, you probably think that. But if you’re a business person, you probably wouldn’t,” Adams said. He added: “What I can tell you is that for hundreds of years, timber was the economy of Southeast Alaska. And I still think it is. And I still think that there’s a lot of revenue. It’s going to put people to work.”

The Kwaan’s push into logging may now be facing its most significant challenge.

A group of dissident shareholders is set to launch a recall campaign seeking to depose the corporation’s leadership.

Critics of Yak Timber had vied for board seats in the Kwaan’s annual election scheduled for late 2021.

But as votes were about to be counted, the incumbent board members postponed the meeting. Their basis, Jensen told me, was “misinformation” flying around social media that the corporation’s attorney warned would have “tainted” the results.

Since then, a new election has been postponed multiple times, and Jensen said she doesn’t expect the next one to occur until April or May.

That’s left six of the Kwaan’s nine board members in their positions who otherwise would have been up for re-election.

“We just can’t trust the corporation to hold ethical elections,” said Amanda Bremner, one of the recall effort’s organizers. “The power lies with the shareholders. If we want to see the change that we want, we have to be that change.”

In the days following my trip, I heard from multiple people in Yakutat about a possible thaw in tensions between the Kwaan and the village’s tribal government, which has stridently opposed logging in the Humpback Creek area.

Tribal leaders, up to that point, had not been able to access the site to look for archaeological evidence and examine the discoveries publicized by Defend Yakutat. But discussions between the two sides were taking place.

A week ago, though, photos quickly circulated among village residents that show freshly logged areas near Humpback Creek, along with heavy equipment near the edge of the bay. Tribal leaders saw that as a huge setback.

“We're very disappointed,” Andrew Gildersleeve, the tribal government’s chief executive, told me by phone. “A lot of effort has taken place from people at the tribe who've been working on this — extended hours, weekends — to try to save Humpy Creek. And the new photos remind us that we've lost, and our very worst fears have come to fruition.”

As to whether an access agreement had been reached, I got conflicting views. Jensen said she promised tribal leaders that they can visit the area when they asked to, later in the spring.

But Gildersleeve’s interpretation was different.

“There's nothing formal or substantial that has arisen from these talks other than a sort of general intent to do something in the future,” he said. “And we believe this to be an immediate crisis.”

Jensen, when I followed up with her by phone last week, acknowledged that Yak Timber has continued logging at Humpback Creek to satisfy its bank, “until we can come up with a new plan.”

But she saw the harvest in a much more positive light, and sent me a different photo from the same area — showing neatly stacked logs, a few stumps and a scenic backdrop of ocean and snow-covered peaks.

“One day, that will be valuable land if we want to do something with tourism,” Jensen told me.

Logging critics, she added, say they want to keep the trees standing for future generations of shareholders.

“But a tree,” she said, “is not going to put a house on the land, or food on the table.”

Northern Journal is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.