New from Nat Herz: Northern Journal

A dispatch from Tokyo, and news on the Alaska Peninsula.

Hi. This is Nat Herz. You may know me from my work as a reporter for the Anchorage Daily News and Alaska Public Media. I’ve lived and worked in Alaska for almost 10 years.

After an extended break and a bit of soul-searching, I’m trying out a new career as a freelance journalist based in Anchorage. I’ll hopefully be doing a few different things — yes, I also co-host a cross-country skiing podcast — and among them will be this new newsletter.

Northern Journal is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

To be honest, I’m not completely sold on newsletters. I’m worried about the fragmentation and polarization of our news media in Alaska and around the country and don’t want to contribute to that; I also think that mainstream outlets like the ADN and APM perform essential services for our democracy and deserve our support. So I hope to continue contributing to publications like those, while at the same time using this platform as a way to share stuff that interests me in a more flexible fashion.

I’m making the newsletter free, and I won’t be publishing paid-only content, but I’m allowing people to buy voluntary subscriptions if they feel the information is worth it. Please forward this edition along to folks you think would be interested, and I encourage you to drop me a line by email, text or phone (907-793-0312) with your suggestions, feedback and tips.

This newsletter will focus on my areas of biggest personal interest, which I hope also will interest you: public lands and waters, climate change, Alaska’s energy and fishing industries, and state and federal government and politics. It will probably evolve as I find a voice and hear from you. Thanks for reading; now, take a little trip with me through Tokyo, the Alaska Peninsula, and U.S. Senate campaign central.

The view, from Asia, of Alaska’s natural gas pipeline

I spent 10 days in Japan last month. I was mostly on vacation — great hot springs, the trains run on time and astonishingly fast — but I also met with a few people in Japan’s energy industry.

That’s because the nation is the world’s largest LNG importer and, importantly, likely the biggest potential buyer of gas from the proposed Alaska LNG pipeline. The state-sponsored project, at a cost of nearly $40 billion, would run some 800 miles from Alaska’s North Slope oil fields to Cook Inlet, not far from Anchorage, then export gas mostly to Asian markets.

The LNG project has generated some headlines in recent weeks: While I was in Tokyo, U.S. Ambassador Rahm Emanuel — the former Chicago mayor and chief of staff to Barack Obama — held an “Alaska LNG Summit,” with U.S. Sen. Dan Sullivan and several state workers showing up in person to pitch the project to Japanese buyers. (I stopped by and ambushed Emanuel, to no avail, but I did spend some time with Sullivan; a little more on that later.)

Since I was in Japan, it seemed like a good chance to try to answer the question that people always seem to ask when they hear about the pipeline project, which politicians have talked about for decades but never managed to pull off: Is it actually going to happen?

Spoiler alert: I still don’t know. But I made some observations and learned a few things on my trip that could add to Alaskans’ understanding of where the project is headed.

First: There have been a couple of major shifts in the past year that are helping boost Alaska LNG’s profile.

The Ukraine war was the biggest one, sending global oil and gas markets into chaos and making Alaska LNG more appealing for potential customers and investors.

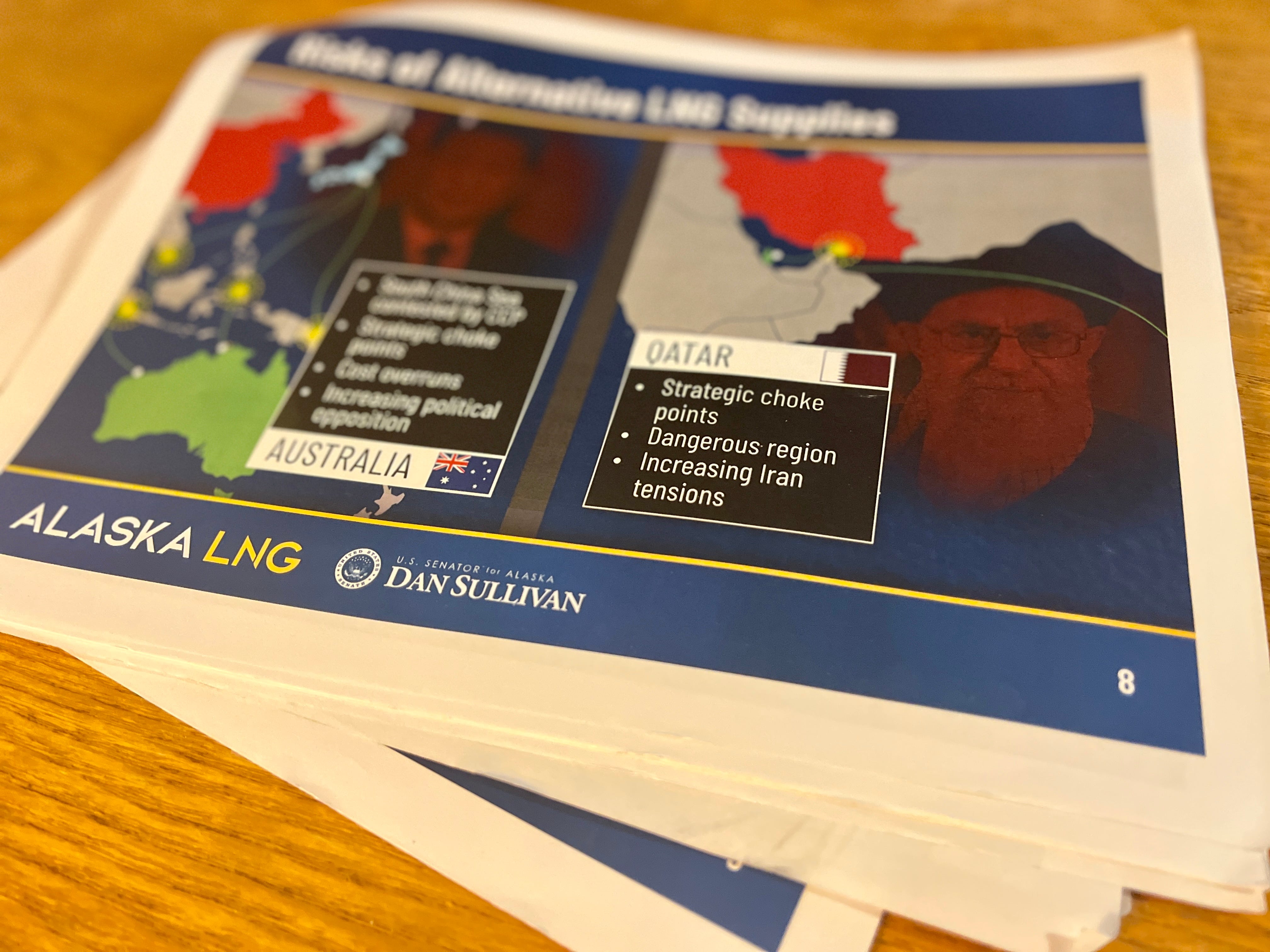

Alaska is (relatively) politically stable, its national government is aligned with Japan, and its location is convenient for Asian customers, unlike competing suppliers’. In his presentation at the Tokyo summit, Sullivan, an Alaska Republican, stressed quick shipping times to Asia from his home state and, with PowerPoint slides featuring red-tinted portraits of Chinese, Russian and Middle Eastern autocrats, pointed to what he described as the geopolitical problems faced by Japan’s existing gas suppliers.

“A lot of where they currently get their supplies have huge risk factors,” Sullivan told me in an interview after the summit. “Putin, global pariah…Mexico, there’s a project down there, but you’ve got corruption.”

Second: In the U.S., both state and federal elected leaders are now sinking significant political capital into Alaska LNG. This is particularly striking because the federal government faces pressure on carbon emissions targets both externally, from activists, and internally, from climate-focused members of the Biden administration.

Sullivan and officials from the Alaska Gasline Development Corp. — the state agency pushing the project — highlighted the participation in the Tokyo summit of both Emanuel and Amos Hochstein.

Hochstein is a former oil and gas executive turned key energy advisor to Biden — the Washington Post calls him the “energy whisperer” — as the president seeks to balance climate goals with the desire to stabilize global and domestic supplies. The Alaska LNG project’s boosters argue that Hochstein’s presence, and the fact that Emanuel had the leeway to organize the summit and issue a press release about it, should help soothe concerns among potential Asian customers that the Biden administration could thwart or delay the project as a way to ensure it hits climate targets or to satisfy climate activists.

It was clear to me from my own meetings in Tokyo — including with a couple of industry officials who served me hot green tea from a ceramic cup but did not want to be quoted — that Japanese buyers see the clear political appeal of investing in or buying from the Alaska project. It would both enhance economic ties with an important ally and provide a safe and stable supply of gas.

But there are also some significant obstacles that are still standing in the way.

First: These types of projects are massive investments. The state currently estimates the cost of Alaska LNG at $38.7 billion, and the project would produce 20 millions metric tons a year of gas — which equates to just over one-fourth of Japan’s annual LNG imports. (It’s likely that the project would sell gas to other countries, too, but the numbers are a good indication of its scale.)

If there was one thing I took away from my reporting in Japan, it’s that companies there are notoriously deliberate. I got an almost knee-jerk response when I asked my sources if they thought that Japanese companies are close to signing contracts to buy Alaska gas, which boiled down to: Japanese companies are very, very, very cautious.

Officials from Alaska’s pipeline corporation say that their conversations with potential customers are progressing to the point of specifics. But my impression from my own discussions is that the events of the past year have driven Japanese buyers in the direction of more seriously vetting the Alaska project, not yet to the edge of signing a legally binding deal.

One thing that I learned could push Japanese industry to move more quickly is if their government gets involved. But that gets to the second major obstacle to the Alaska project: Japan’s own climate goals. The country is aiming for “net zero” greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, which will likely make the government wary of endorsing or supporting large-scale, long-term fossil fuel projects like gas pipelines. (To combat that problem, Alaska LNG boosters are developing new components of the project that could potentially sequester carbon emissions and/or produce cleaner hydrogen fuel.)

And while Americans tout the geopolitical upside of an LNG alliance between Japan and Alaska, Japan still doesn’t seem to be placing too much of an emphasis on geopolitics when it comes to energy supplies: Just one week ago, officials in Tokyo announced that a Japanese consortium is sticking with its investment in a Russian oil and gas project, in spite of the war in Ukraine.

Alaska’s project faces competition, too — a major project in British Columbia that already exports to Asia, for example, is eyeing an expansion. And a new report released this week said that new planned global natural gas development, in the wake of the Ukraine invasion, is five times as much as is needed to replace Russian production.

Don’t take it from me: I’m just a dude with a liberal arts degree who talked to a few people in Japan about gas. The ultimate test of the viability of Alaska’s project will be whether Japanese and other Asian buyers sign on the dotted line, likely in the next year, before markets fully settle down in the wake of the Ukraine war. Frank Richards, the head of the state pipeline company, said as much in an interview in his Midtown Anchorage office Thursday.

“The market is going to decide,” he said.

Richards told me that his agency isn’t trying to drum up interest from customers so much as hammer out details with partners. And he said he thinks his agency will need less than a year to reach agreements with them.

“Their interest is there,” he said. Referring to Asian customers, Richards’ spokesman, Tim Fitzpatrick, added: “We’re not out there looking for business. We’ve kind of found our dance partners — at least some of who our dance partners will be — and we’re talking terms with them.”

Major news on a decades-old Alaska lands controversy

The 9th Circuit Court of Appeals issued a major decision Thursday, agreeing to rehear a high-profile case that centers on a proposed road through a national wildlife refuge on the Alaska Peninsula.

The case is tied to one of the state’s most emotional land disputes. Residents of the largely Indigenous fishing town of King Cove have pushed for decades for road access through the Izembek National Wildlife Refuge, which is treasured by conservationists for its bird, fish and wildlife populations. On the far side of the refuge from King Cove is a jet runway in the tiny community of Cold Bay, which King Cove residents say would provide them with much more reliable airport access for medical evacuations and general travel. (Conservation groups dispute that; for more background, read my story from Interior Secretary Deb Haaland’s visit to the community last spring and a primer on the controversy I wrote in 2017, and check out ADN photographer Marc Lester’s shots from Haaland’s visit and the Izembek refuge below.)

The road proposal has ping-ponged back and forth between Republican and Democratic presidential administrations. The court case hinges on the legality of a land trade to facilitate the road’s construction that the Trump administration, with encouragement from U.S. Sen. Lisa Murkowski and other statewide elected leaders, worked out with King Cove’s Alaska Native village corporation. But the development of the road, which would run through a congressionally-designated wilderness area, has been on hold amid a lawsuit challenging the land trade, which was originally filed in 2019.

A U.S. District Court judge, John Sedwick, declared the land trade illegal in 2020.

But in a subsequent ruling earlier this year, a three-judge appeals panel from the 9th Circuit reversed Sedwick’s decision. They said that a landmark bill passed by Congress in 1980, the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act, gave the executive branch discretion to “strike an appropriate balance between environmental interests and ‘economic and social needs.’”

That opinion was from two Trump-appointed judges; the third judge on the panel, a Clinton appointee, dissented.

The conservation groups that originally filed the lawsuit saw the ruling as setting a dangerous precedent — that, in their view, economic interests could threaten ANILCA’s protections for subsistence and conservation not just in Izembek but in other Alaska refuges and parks. They asked for what’s known as an “en banc” rehearing, in which the case is considered by a larger, 11-judge appeals panel.

It’s extremely rare for the 9th Circuit to grant en banc review; a 2017 publication said that the court gets about 1,500 requests a year, and grants roughly 20, for a rate of just over 1%.

Numerous parties weighed in on the request.

The Biden administration, which, to environmental groups’ frustration, has defended the land exchange, filed a brief in support of the three-judge panel’s ruling. NANA Regional Corp, the Alaska Native corporation for the northwest part of the state, filed a friend-of-the-court brief that also opposed a re-hearing, saying that a reversal could eliminate its ability to engage in "meaningful" exchanges of its own lands with the federal government. Jimmy Carter, the former president who signed the 1980 lands bill into law, filed his own brief urging that the case be reheard.

For such a request to be granted, a majority of the 9th Circuit’s judges have to vote in favor of it — which is, in and of itself, usually an indication that a significant number of judges feel that the requester’s case has merit.

The 11-judge panel that will now re-hear the Izembek case is also likely to have an ideological bent that’s more favorable to the conservation groups than the three-judge panel, which had the two Trump-appointed judges. That’s because the judges for the larger panel are chosen at random, and of the 29 active circuit court judges, 16 were appointed by Democrats and 13 by Republicans.

The judges will be chosen Monday, according to the 9th Circuit’s rules; oral arguments are set to take place in California next month. I plan to keep following this case as it develops.

Campaign odds and ends

Those of you who know me know that I have something of an unhealthy obsession with campaign finance data. I missed many reports and deadlines during my extended break from work, and I haven’t completely caught up yet, but a couple of things jumped out at me during a quick review over the past few days.

One of those things was a super PAC that, in somewhat low-key fashion, dropped some $2 million into the U.S. House race in support of Democrat Mary Peltola, according to Jim Lottsfeldt, one of the strategists working on the effort. The PAC, Vote Alaska Before Party, was originally spearheaded by the Juneau-based Alaska Native regional corporation, Sealaska, but it ultimately got most of its cash from House Majority PAC, a national Democratic group, Lottsfeldt said.

The group's campaign finance disclosures only show about $800,000 in receipts — $650,000 from House Majority PAC, $90,000 from Sealaska and $50,000 from another Alaska Native regional corporation, Chugach — but because of reporting requirements, they don't yet cover the last week before Election Day. Lottsfeldt told me there was some $1 million in TV advertising supporting Peltola, and then, in the last few days before Election Day, the group began attacking one of her Republican opponents, Nick Begich III, about “outsourcing jobs to India.”

The significant spending from House Majority PAC is interesting because the group, much to the frustration of Peltola and her campaign staff, hadn’t invested in the August special election in which she was first elected. But the group clearly now sees Alaska as competitive turf.

One other thing I thought was interesting was how the main pro-Murkowski super PAC, Alaskans for L.I.S.A., raised and spent its cash in the lead-up to Election Day. It raised some $5 million in support of her re-election, according to its latest disclosures — more than half as much as Murkowski raised for her entire campaign —and spent it with fairly little scrutiny.

Just in the first three weeks of October, for example, the group received late-in-the-game, five-figure contributions from Native corporations, $100,000 from billionaire hedge fund manager and NFL team owner David Tepper, and $15,000 from the company behind the contentious Donlin Gold project in Southwest Alaska.

The group, spearheaded by Lottsfeldt, lobbyists Mike Pawlowski and Jerry Mackie and attorney-operative Scott Kendall, also brought on longtime legislative aides Amory LeLake and Joe Plesha as "strategy consultants." LeLake and Plesha were paid $4,500 and $15,000, respectively, since August, according to campaign finance reports.

Northern Journal is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.