Shrinking prize: Amid halibut's decline, challenges mount for Alaska and Washington fishing crews

Scientists haven't reached a consensus about the forces that have driven down halibut stocks. But the decline is hitting the harvest hard.

This story is part one in a three-part series. It was supported by grants from the Pulitzer Center and the Alaska Center for Excellence in Journalism, and published by Northern Journal in partnership with the Anchorage Daily News and the Seattle Times.

ABOARD THE ORACLE, North Pacific — Skipper Robert Hanson seeks halibut on a stretch of graveled sea bottom ripped by the powerful tides of the Aleutian Islands. There, he drops a mile of line carrying nearly 600 baited hooks.

Hanson, for more than three decades, has roamed the waters off Alaska to find halibut, long-lived flat fish that can reach lengths of up to 8 feet.

During his career, the fishing has become a lot tougher, and, last year, a fall fishing trip in the Bering Sea was an outright disaster. A once prime area was largely barren of fish. In the few spots where he still encountered halibut, hungry killer whales stripped away most of the catch before he could bring them onto the boat.

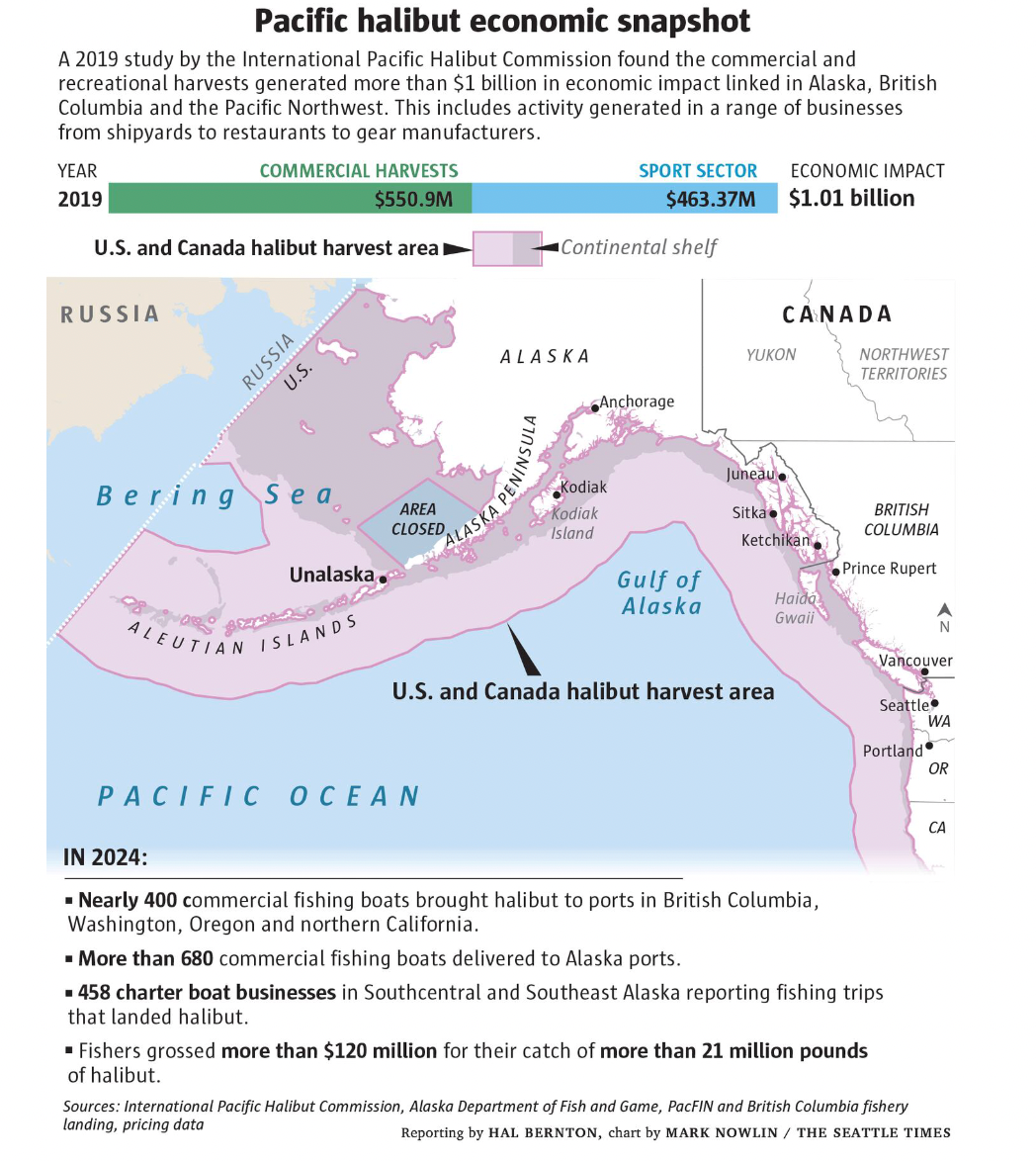

Hanson’s struggles come as halibut stocks have plunged from record highs of the 1990s across a broad range of the North Pacific. The fishery has long been one of the economic mainstays of small-boat fishers in Alaska, British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest. These fish are also prized by sport anglers, sustaining hundreds of charter boat businesses, and taken in subsistence harvests largely by Indigenous peoples.

Halibut now appear to be at, or near, their lowest point of the past century.

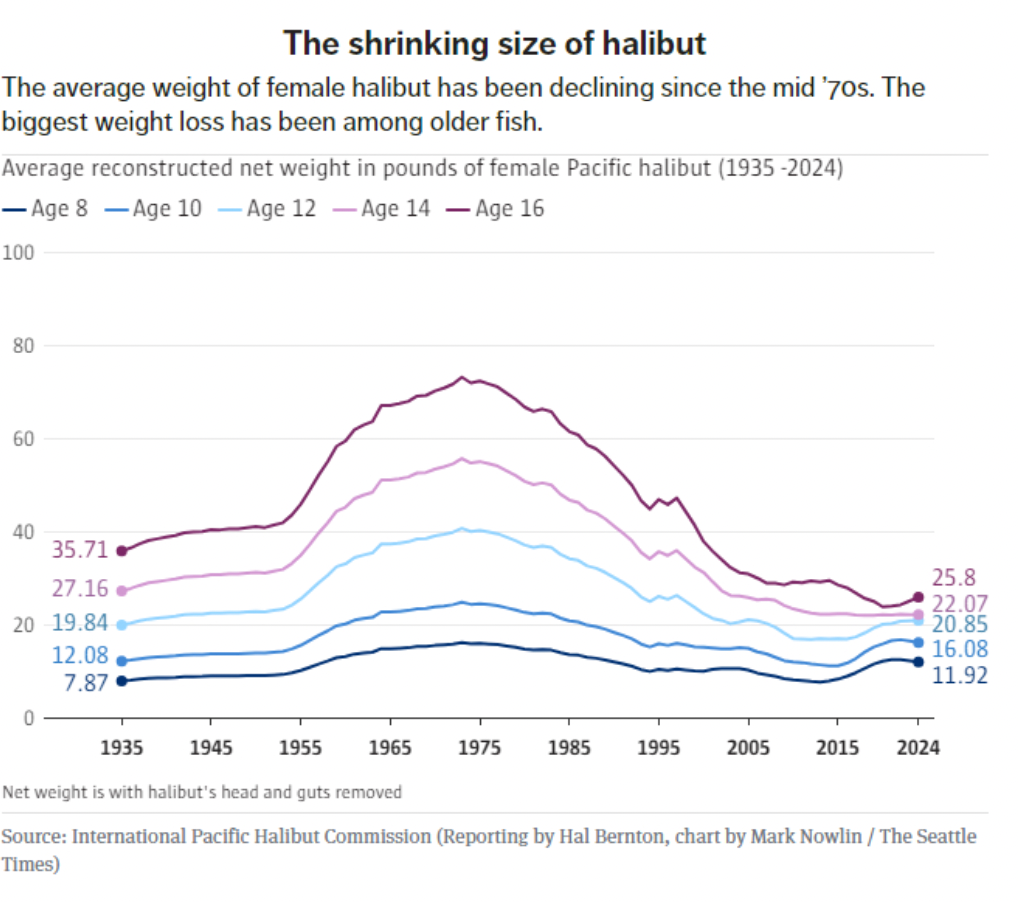

Researchers have found far less mature fish swimming in the North Pacific, and a startling downsizing of older fish. In 1973, an average 16-year-old halibut weighed 73 pounds. In recent years, an average fish the same age dropped to just less than 26 pounds, according to data compiled by the International Pacific Halibut Commission, which sets annual harvest limits.

For Hanson, the dramatic downturn has been a punch in a gut to a fishery that is his livelihood — and his passion.

“Just scratch, scratch scratch,” Hanson says. “There are no big schools of fish.”

—

The Oracle leaves the dock in Unalaska early on a Sunday morning. Hanson in the wheelhouse guides the boat out of the harbor for the 5-hour trip to the fishing grounds.

The weak light of dawn spreads under a gray sky, revealing island flanks of grass, shrubs and — in some areas — fortresslike cliffs.

Hanson sips on a cup of coffee, a thin man with big square glasses that — if not for a wild tangle of graying hair and his deeply weathered skin — would give him an almost professorial appearance.

Hanson spends his offseason in Maui, where he surfs and plays pickleball and tennis. He lived for much of his youth in Kenai, Alaska, where his father was a state judge but never thrived within the confines of formal education. He harvested salmon as a teenager, and, by the late 1980s, had embraced commercial fishing as a career and moved into longlining for halibut.

“I love being on the ocean,” Hanson says. “It just makes me feel at peace, even if it’s not that peaceful.”

Among the Oracle’s crew, Hanson has a reputation as a skipper who knows how to find halibut but also can be a harsh taskmaster.

“Robert is a grinder. He’s got fish to catch,” says Chase Oleyer, one of the four crew members who joined Hanson on this June fishing trip.

Good bait is key to a successful halibut trip. Hanson favors octopus, so before leaving port, Oleyer spent most of a day thawing carcasses, then cutting them into hundreds of pieces.

Underneath a metal roof that shelters the stern of the Oracle, two other crew members put octopus chunks onto circle hooks attached to 900-foot sections of lines known as skates.

—

Hanson is part of North Pacific harvests that began in the late 1800s, when sailing dories and schooners supplied fresh fish to British Columbia and Washington ports. More than a century later, when Hanson first entered the Alaska fishery, the harvests had evolved into notorious mad-dash derbies as thousands of fishers raced out to sea to grab as much fish as possible during a few annual openings that were as short as 24 hours.

The derbies brought huge amounts of halibut to shore, sometimes resulting in bargain-basement prices for consumers as seafood dealers — facing glutted markets — sought to move fresh fish before it deteriorated. The derbies were also chaotic and at times dangerous, as fishers, to maximize their catch, sometimes opted to fish through rough weather. They would overload their boats, which sometimes sank in one of the most accident-prone fishery harvests in America.

The 1995 Alaska harvest marked the start of a new era, when fishers were allocated individual quotas they could catch at any time during a season that stretched for most of the year.

This slower-paced harvest improved safety. And the slower flow of halibut onto the market pushed up prices, a boon for fishers but not so great for budget-conscious consumers as the flaky white fillets morphed into one of the most high-priced offerings at seafood counters.

The current harvest level is the lowest in more than 120 years, and the diminished supply has pushed prices even higher. Fishers have been paid more than $8 a pound for halibut that retails for more than $20, sometimes more than $30, a pound.

The prices are so high that Burgerville, a Northwest fast-food chain, opted to take halibut off the menu this summer for the first time in 40 years.

Hanson says he hopes this year’s high prices can help him rebound from the financial blow he took during last year’s season.

“This is big money. I need a big trip,” he says.

—

Fishery scientists have not forged a consensus about the forces that have driven down the halibut stocks.

Climate change has brought marine heat waves, and new combinations of ocean conditions, some of which could have impacted the survival of young larvae. But so far, there’s no research that strongly links these shifts to the halibut’s current plight, according to Ian Stewart, a biologist with the halibut commission.

Some biologists say that halibut’s decline largely reflects a natural low point in cyclical declines in populations that unfold even without fishing. In the years ahead, they say they expect halibut populations, and the size of the average fish, will increase.

Others say that fishing pressures might have significantly contributed to the decline of both the numbers of halibut, and their size, by removing some of the biggest and fastest-growing fish, which most often are females of prime age for spawning.

From 2006 through 2012, the commission relied on flawed stock assessment models that significantly inflated the amount of North Pacific halibut, according to interviews with current and former staffers and a review of internal commission documents. That meant halibut were harvested at significantly higher rates than the levels intended by the commission, according to Tim Loher, a fishery biologist who worked at the commission for almost 21 years.

The commission manages Pacific halibut as one U.S. and Canadian stock but divides the harvest into different ocean zones, each with a separate limit on the total amount of fish that can be caught. Longliners in the Bering Sea, which includes nursery areas for fish that migrate as far south as the Pacific Northwest, have faced the biggest challenges catching halibut. In 2024, they caught less than half the Bering Sea quotas set by the commission, and are unlikely to do much better this year.

“I have never participated in any other fishery where I can’t catch my allocation. Blank hook after blank hook one day … undersized halibut with few legal halibut on other days,” wrote Buck Laukitis, a veteran longliner and owner of the Oracle and two other vessels, in a 2024 commentary to a federal fishery council.

“We can’t catch fish that aren’t there … I am a commercial fisherman begging regulators to be conservative. How ironic?”

Stewart, the halibut commission biologist who heads up stock assessments, acknowledges that the dismal harvests of the Bering Sea halibut fleet are a troubling sign.

“There’s some risk associated with a place we have never been before,” he says. “And that’s where we think we are right now.”

—

Hanson dons a faded blue jacket and black rain pants on the first day of the June trip. Then, he descends from the wheelhouse to the deck, grabs a long metal gaff and hangs a coconut-fiber mat along the starboard rail to cushion his body.

The baited lines had soaked for several hours in a 720-foot-deep canyon that, due to its proximity to Unalaska Island, is off-limits to trawl vessels that pull large nets along the sea bottom. The bottom had a carpet of mussels and scallops, which nurtured a mix of sea life that Hanson hopes will include halibut.

Time to check the lines.

“Let’s go, boys,” Hanson calls.

On some boats, a crew person handles the critical task of bringing on board the halibut. Aboard the Oracle, Hanson has claimed that job for himself, and had a second set of controls on deck that allow him to haul in the fish as he steers the boat and runs a hydraulic winch required to muscle up the gear from the bottom.

The first longline skate has dozens of halibut, and the second skate is even better, bringing in some fish that weigh 50 to 60 pounds. There are also small halibut under the 32-inch-long legal limit. When those fish come aboard, Hanson has to race to shake them loose before they are sent through a bait stripper that rips out the hooks with one brutal tug that can do serious harm to their jaws.

Oleyer cradles these small halibut, sometimes giving them a brief kiss before tossing them overboard. In the Bering Sea and North Pacific waters around the Aleutian Islands, the commission estimates that 90% of the discarded longline halibut survive.

The lines, on several sets, are full of Pacific cod, some of them weighing 20 or even 30 pounds each. They could yield flaky white fillets for fish and chips. But the cod will not keep in the hold as well as halibut, and Hanson’s shoreside buyer would not purchase these fish.

Some of the cod are kept for bait. The rest were discarded, and many — with their bladders distended by the rapid ascent to the surface — may not survive.

The longlines, on occasion, also bring on board big octopus weighing 30 or 40 pounds. The octopus had tried to feast on some of the hooked halibut and cod, and held onto their prey as the lines were hauled up to the surface.

The octopus are hung on a rack, and eventually cut up into pieces and placed on hooks to catch more halibut, one small part of the crew’s marathon workdays that stretch for as long as 18 hours. There are lines to be coiled, halibut to be cleaned, then stowed into a hold, where a crewman will periodically shovel layers of ice to keep them cool.

The crew heads to the galley only briefly to refuel. On one evening, the meal consists of barbecued pork ribs, hash brown potatoes left over from breakfast and cold-cut sandwiches.

For Hanson, amid the hunt for halibut, food seems to be almost an afterthought. One evening, he makes dinner out of a quesadilla, fortified with a slice of ham, that he eats while on a wheelhouse watch.

The sheer physicality of deck work can cause bodies to break down, and tempers to fray.

Steve Legino, a Bering Sea crabber who turned to longlining, has a damaged disc in his back. At one point during the trip, he wraps an orthopedic belt around his midriff and works through the pain.

Oleyer last year suffered severe blisters on his hands worn down by many days of cutting bait. These wounds wore so deep he could see down to bone. On this trip, his swollen hands ache, and he strips down — before heading out on deck — to rub CBD oil into his back.

“Typically the first two trips of the season are the hardest,” Oleyer says. “The pain is horrible but you just got to block it out. The hands. The shoulders. The back. The knees. Anything that bends. You have to embrace ‘the suck’ if that’s what it takes to get the job done.”

—

By late Sunday evening, the Oracle’s catch tallies some 5,000 pounds. During the halibut boom years, that would have been a respectable but not extraordinary haul. For Hanson, in the aftermath of last year’s bleak harvest, this is very good fishing. So, rather than prospect elsewhere, he spends the next three days dropping his gear — over and over — largely within the confines of the narrow canyon.

The final day of longlining begins with disappointments. The gear comes in with lots of empty hooks, or Pacific cod and undersized halibut that have to be thrown back. Early in the afternoon, Hanson encounters a large snarl of hooks wrapped around a line, prompting a volley of curses.

Later, a strong pulse of fish come on board. Some were huge, close to 100 pounds. Hanson’s frustrations with the tangled gear, weak sets and a crew that rarely seems to fully meet his expectations melt away. He cackles like a kid, whoops with joy.

Oleyer works at a butchering table at the center of the boat, wrestling the fish into submission. Some he quiets with strokes. Some he bonks with a short metal bat before bleeding and gutting them with a sharp knife.

Hanson lands halibut so fast that Oleyer can’t keep pace. One large halibut slides off the table, its powerful tail thrashing on the deck even as more halibut move up the conveyor and onto the table.

Well past midnight, the last halibut comes on board.

The crew tops off the catch in the hold with more ice and washes down the deck. Hanson takes a wheelhouse watch for a daylong 130-mile cruise to the processing plant on the eastern edge of the Aleutians, where he will deliver the catch: 21,000 pounds of halibut worth more than $140,000.

Along the way, Hanson looks wistfully at a map on his screen, pointing to places where he used to find lots of halibut. He says he doubts he will live to witness a return to such abundance.

But he is ready to savor one good trip.

“We found fish that were healthy. They were fat, strong,” Hanson says. “That doesn’t mean the fishery is saved. It just means that we got lucky.”

Northern Journal runs on contributions from readers. If you appreciate in-depth journalism like this and you're not already a paid subscriber, please consider a voluntary membership.