The great Alaska walrus caper of 2023

How did a walrus get four miles from shore, to the middle of an Alaska oil field? I hunted for answers — and found them.

Northern Journal is a newsletter written by me, Anchorage journalist Nat Herz. It’s free to subscribe, and stories are also free to Alaska news outlets to republish through a partnership with the Alaska Beacon.

My goal is reaching the broadest possible audience of Alaskans. But if you can afford it, please consider supporting my work with a $100 annual or $10 monthly voluntary paid membership — these are currently my only sources of revenue for this project. Your support allows me to stay independent and untethered to the demands of the day-to-day news cycle. If you’ve already subscribed, thank you.

As a rule, I almost never bite on PR pitches; they tend to be almost offensively irrelevant to readers. (From this week: “The Greenwashing Of Beauty: How Brands Can Clean Up Their Act.” “Media Opportunity: The Mega Millions Expects Record Number of Players Tomorrow Chasing Happiness in The Wrong Place.”)

On Thursday, however, an email came in that got my attention. It was about a walrus rescue.

A walrus rescue, on its own? Announced by the Alaska SeaLife Center, whose storylines about cuddly marine mammals typically prove irresistible to editors, reporters and readers alike?

Not a story for Northern Journal, which sticks to stories that won’t get covered anywhere else.

Except for a sentence in the center’s press release that I couldn’t get past: “The young walrus was spotted by workers on Alaska’s North Slope, about four miles inland from the Beaufort Sea.”

Four miles?

“Observers reported a notable ‘walrus trail’ on the tundra, close to a road where he was discovered, although it is unknown how he arrived inland.”

Four miles is a long way for me to walk, and I have running shoes. And knees.

While I’m not a pinniped expert, I was prettttttty sure that four miles was an absurdly long way for a 200-pound male walrus calf to wander from the ocean.

This was no longer a walrus rescue story.

This was a walrus mystery.

My email to the SeaLife Center, 5:25 p.m. Thursday: “Hi there, I'm a freelance reporter in Anchorage — I'm curious about this and just want to clarify: The baby walrus was four whole miles from the ocean?? Were there any streams or other bodies of water nearby that it might have swum up? Or does it really seem like it somehow crawled that far?”

SeaLife Center, 12 minutes later: “Yes, the estimate was four miles away from the coastline. Great question that we wish we knew the answer to! There were rivers in the general area where he was found, but not in the immediate area. He could have swam up a river part of the way, then walked. Possibly walked the whole way. We wish we knew!”

On Friday morning, I woke up and called Rebecca Boys, a spokesperson for ConocoPhillips, which the SeaLife Center, in its press release, said had flown the walrus off the North Slope. The press release was a bit vague about who exactly had rescued the walrus originally, but Conoco seemed like a good place to start, and another oil industry source told me that the company was the one involved.

Conoco, as you probably know, is a multinational, publicly-traded oil company, and it is not especially often that I call Rebecca about joyous occasions. Conoco is embroiled in multiple lawsuits related to its planned Willow development on the North Slope. It has also made headlines recently for a $900,000 fine proposed against it by state regulators after a gas leak.

Rebecca, I said, can I talk to some of your people about their heroic walrus rescue. This is fun, I added; it is not about, like, a gas leak!

Rebecca said she would get back to me.

A couple of hours went by. I started to get a sneaking suspicion that maybe ConocoPhillips would not be volunteering all the adorable details atop which it was almost certainly sitting.

Email from Rebecca Boys to me, 11:49 a.m.: “Hi Nat, What I can say on the walrus calf is that ConocoPhillips is honored to have been a part of the rescue and care of the walrus calf. We were happy to be able to transport the calf directly to the Alaska Sealife Center. This is an example of a network of caring neighbors who work together for the best possible outcomes. Alaska is fortunate to have an organization like the Alaska SeaLife Center where patients can be cared for by veterinary professionals. He is in great hands, and we look forward to following his story.”

Me too, Rebecca. BUT THERE’S A HUGE HOLE IN HIS STORY THAT ONLY YOU CAN FILL.

Email from Nat Herz to SeaLife Center, 1:58 p.m.: “I didn’t get much from Conoco and wondering one detail - is there any more precision you can provide on the location it was found? Like near a particular oil field or landmark?”

SeaLife Center, 2:55 p.m.: “Unfortunately, that was all the information that we were given. ConocoPhillips said they provided a statement with what they knew as well.”

In the mean time, I called up a walrus expert to make sure that it is, in fact, legitimately bizarre that a walrus was four miles from the ocean. Actually, I called, like, two walrus experts repeatedly, without getting them to pick up the phone, before I remembered the name of a third walrus expert.

Walrus expert No. 3, Tony Fischbach from the U.S. Geological Survey, immediately confirmed my suspicions that the calf’s location was weird. And he even told me that there’s probably some “investigative reporting” to be done here.

Finally, SOMEBODY validating me.

Seeing as Conoco was no help, I started badgering government agencies.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Alaska office has a Pacific walrus program, and, according to the SeaLife Center’s press release, the agency had approved the calf’s rescue plan. But their walrus expert was out of the office and not answering his cell phone.

The Alaska Department of Fish and Game’s staff? “They got a notification that it happened,” Rick Green, the department’s spokesman, told me. “But they had no hand in it.”

It was three o’clock; time was running out.

I’d texted one last source at another government entity. He said he’d look into it. Then, he texted me back: “We were not involved, but I can forward you an email.”

An email! A document! Jackpot.

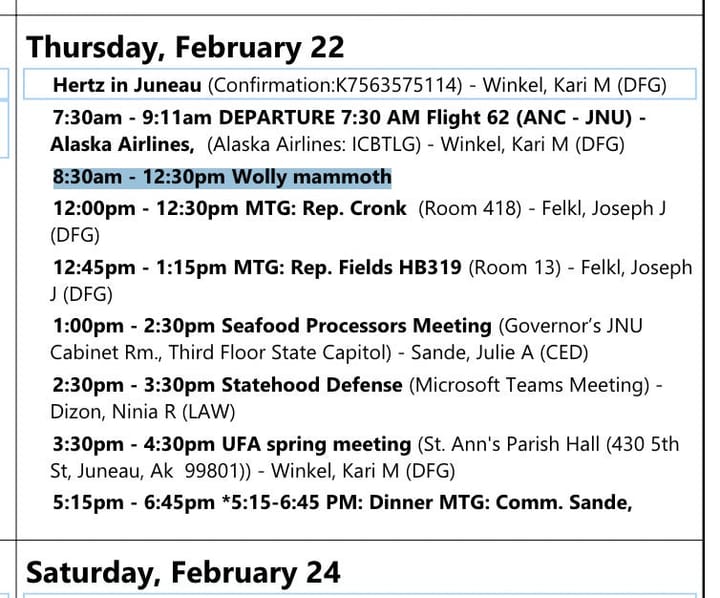

The email, it turned out, was a report from a senior environmental coordinator for biological sciences at Conoco, Christina Pohl. Here it is:

Just a courtesy notification to let you know that an orphan walrus calf of the year crawled up on one of our roads in the Alpine Oilfield yesterday evening (7/31/2023) around 1940 hours. Immediate notifications were made to the National Marine Fisheries Service stranding hotline and contact made with the Sealife Center who coordinated permissions with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Under direction of the Alaska Sealife Center/USFWS the calf was collected and moved to one of our warehouses for overnight safekeeping and to get it out of the elements. It is under constant care/supervision while in our "custody". We didn't have a weather window this morning to get the calf to Deadhorse for the Alaska Airlines flight, so we are just flying the calf directly to Seward today for transfer to the Sealife Center Team.

While walrus are extralimital to the Beaufort Sea coastal area it is even more extraordinary to have one show up on our road system so far inland!

The approximate location of walrus being found was N 70.3046, W -151.2108, along the main road between K-Pad and GMT1/MT6, just east of the turnoff to CD5. We believe it came up the Tinmiaqsiugvik River. There was an obvious "walrus trail" through the tundra where it came onto the road (from the South).

Please note that this area is approximately 4 miles from the Beaufort Sea Coast and the Colville River, although the Tinmiaqsiugvik River is quite a bit closer (1.5-2 miles depending on where it may have left the River).

This was an exceptionally satisfying dispatch to obtain because it answered multiple burning questions.

First, the actual place (with coordinates!!) where the walrus was discovered. On a road! In the middle of an oilfield!

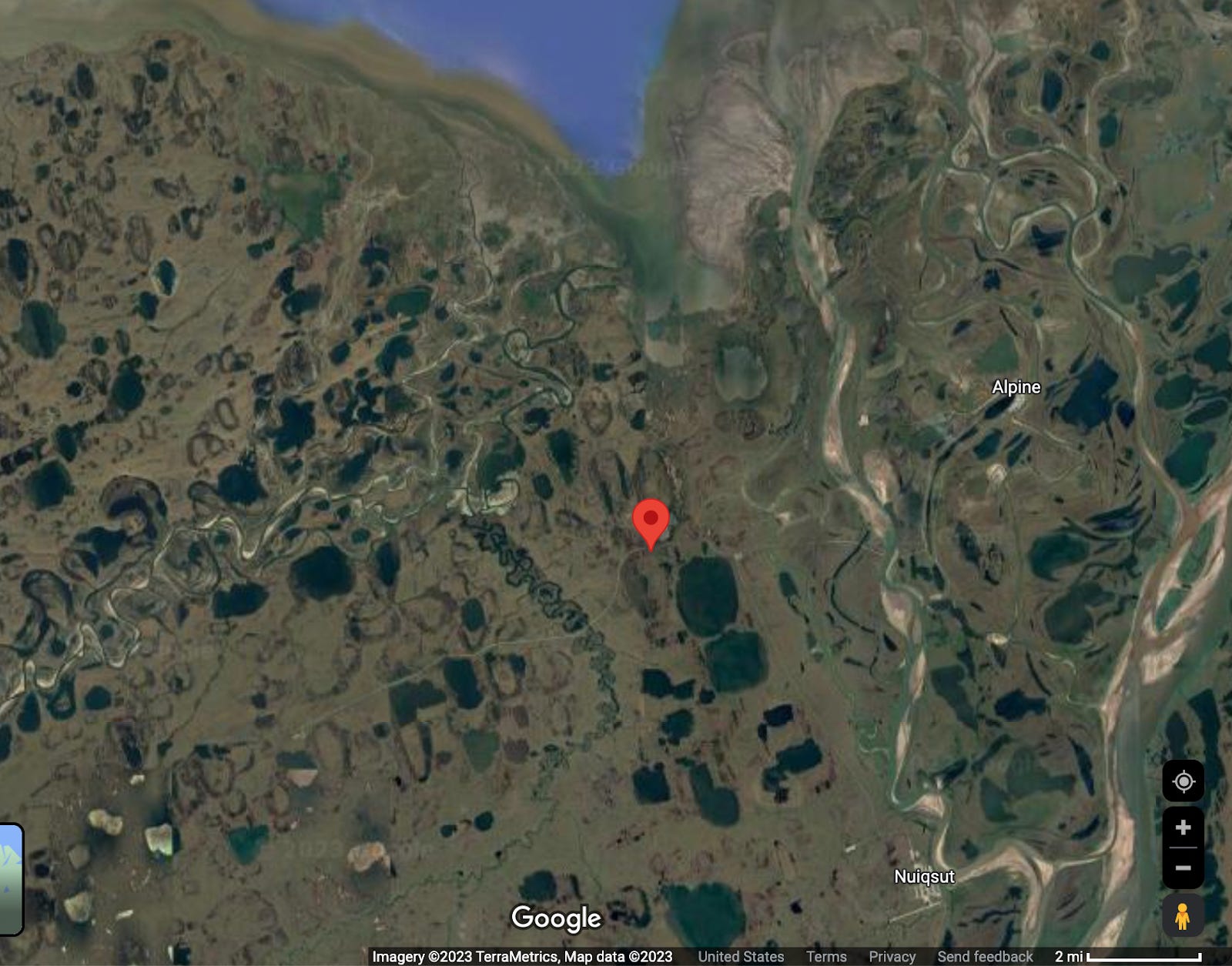

Second, yes, the walrus was four miles inland. But really, it was only a couple of miles from a river that it could plausibly have swum up. Here is a map, with the caveats that Northern Journal is a one-person operation, that the one person does not have any competence in the field of graphic design and that this tale is really not my most serious journalistic endeavour.

The pin shows where Pohl said the walrus was found; the Tinmiaqsiugvik River is the tight squiggly line just down and to the left.

Given that the discovery turned out to be not far from the Iñupiaq village of Nuiqsut, I called an elder there, Rosemary Ahtuangaruak. She said she’s seen bearded seals in the Colville River next to the village, which is even further inland — not so much with walrus, though.

“It’s a very, very rare event,” she said.

A little later, I finally got walrus expert No. 2 on the phone: Jim MacCracken, who ran the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Alaska walrus program for nine years and is now retired. MacCracken informed me that walrus, from a technical standpoint, do kind of have knees, although they bend in the opposite direction of a human’s.

My mistake.

Like Fischbach and Ahtuangaruak, MacCracken said it was “rather strange” to find a calf so far inland. He’d only ever heard of one other case like it, where the remains of a walrus were found “a mile or so” inland on the Kuskokwim Delta in Southwest Alaska.

“I mean, they typically don’t get past the beach. They’re pretty close to water all the time — maybe a hundred feet or so,” he said.

Both MacCracken and Fischbach, the other expert, noted that walrus calves typically stay with their mothers for a long time — their first two years of life.

Given that this one had not reached that age, Fischbach speculated by email that its loss of the maternal connection may have fueled the calf’s unusual wanderings: “Certainly, given the strong dependence that walrus calves have on their mothers and their strong bonds that they have, I can imagine that a calf separated from its mother may undertake extraordinary measures to search for her, even if it were really in the wrong direction.”

He added: “If it were 200 pounds and had time, well, this may well be within the realm of a calf’s ability. Though, it is very sad to consider how very desperate this calf must have been to reunite with its mother.”

There is a silver lining to this story, however, which is that the calf is now getting what the SeaLife Center, in its press release, called “round-the-clock ‘cuddling’” to emulate “maternal closeness.”

(In fact, I am told by a source familiar with the walrus’ care that such cuddling began on the North Slope soon after its discovery, at the SeaLife Center’s instruction.)

Since its delivery at the SeaLife Center via Conoco’s de Havilland Twin Otter, in a big plastic fishing tote with air holes, the calf has been improving — though he’s not out of the woods yet, said Carrie Goertz, a veterinarian who’s the center’s director of animal health.

The still-unnamed walrus had some serious gastrointestinal issues, an eye infection and some small lacerations and abrasions, Goertz told me late Friday, and so far he's been given electrolytes, a baby formula-type beverage and some antibiotics.

“He’s gotten more mobile, more vocal, more interactive — even expressing some annoyance from time to time, which is always great to see that he has the energy to make his feelings and his needs known,” she said.

Goertz has not personally taken any cuddling shifts. But she has spent some time “hanging out” with the calf.

“He is very cute, and it is very rewarding,” she said. “It fills your heart to see how much he wants to snuggle up against you.”

Northern Journal is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.