Trump has given new life to the Ambler Road. But it’s still not a sure thing.

Litigation, financing and skepticism from Alaska Native landowners still stand in the project's way.

In-depth journalism takes time and money. Northern Journal runs primarily on voluntary memberships from readers. If you want to see more stories like this one, please consider subscribing. If you're already a subscriber, thank you.

President Donald Trump surprised skeptics of the proposed Ambler Road this week, ordering his administration to approve the project’s federal permits within 30 days.

His decision aims to reverse the Biden administration’s denial of the proposed mining road by invoking an obscure provision in a 40-year-old law — a legal mechanism that, observers say, had never been used before this week.

But critics of the project note that substantial obstacles still stand in its way: pending lawsuits over permits; uncertainty about who’s going to pay for the road; and longstanding tensions between the state agency that’s pushing the project and two Indigenous-owned corporations with land along the route.

“It is not over,” said Bridget Psarianos, an attorney with Trustees for Alaska, a conservation-oriented law firm that’s disputing the road’s environmental approvals in an ongoing court case. “There is still a lot of fight left in this issue.”

That’s a sharply different outlook from the one voiced by Trump’s interior secretary, Doug Burgum, at a White House news conference Monday. He said he expects construction of the road to begin in the spring.

“We’ll get it done in less than a year,” Trump added.

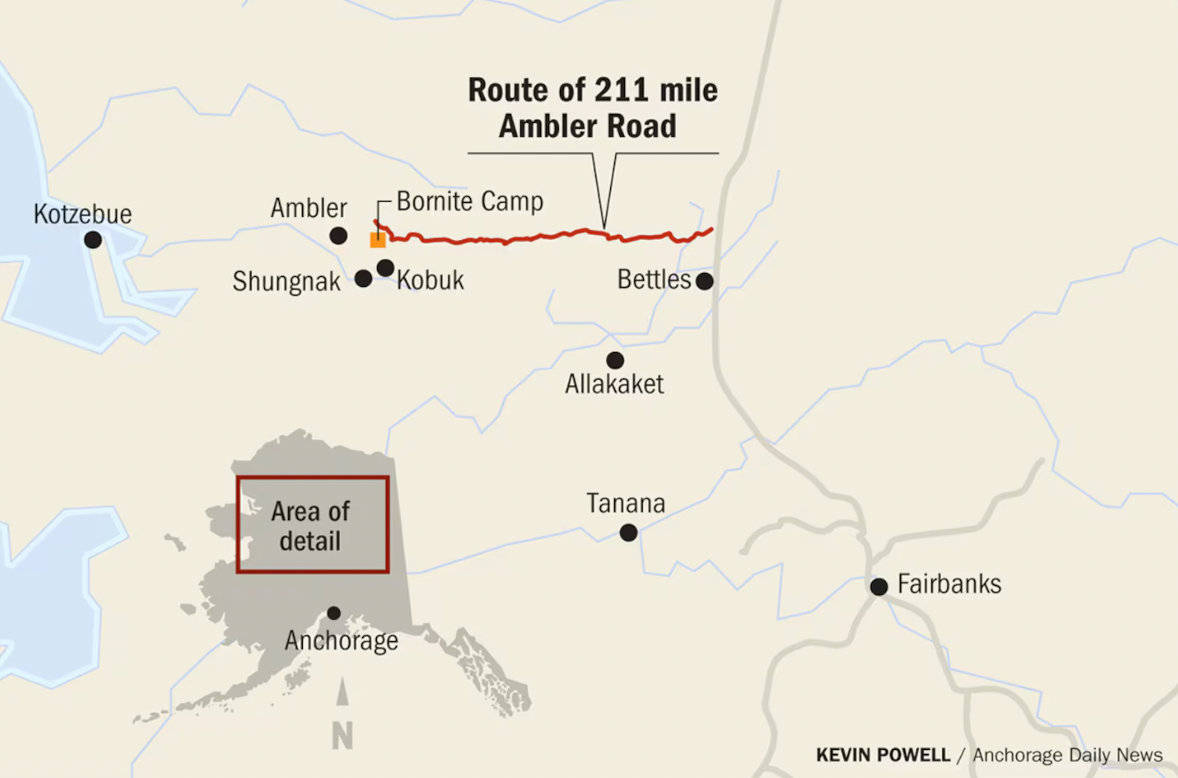

The move appears to represent a major step forward for the project, which would connect a remote corner of Northwest Alaska to the state’s road system and allow a handful of mining companies to access mineral prospects in the mountains of the southern Brooks Range.

But neither Burgum nor Trump explained how, exactly, their stated timeline would be possible, given the hurdles the project still faces. Even the road’s supporters inside Alaska have been more cautious in responding to the news.

The agency pushing the project, the Alaska Industrial Development and Export Authority, or AIDEA, declined to make officials available for interviews this week.

Fierce debate

The Ambler Road has been debated for years, fueling fierce divisions in Northwest Alaska and around the state.

Supporters, including mining companies, elected officials, and some corporate and tribal leaders in the region, view the project as a job creator and a needed boost for the small economies in the rural villages along the road.

Critics, including other regional tribal leaders, conservation groups and outdoor recreation enthusiasts, say it would mar a wild stretch of the Arctic and risks harming wildlife and subsistence harvests that many people in the region depend on. The project would cross nearly a dozen rivers and thousands of streams and is within the range of a major caribou herd.

The project initially gained approval during Trump’s first term but was halted last year by the Biden administration. On the first day of his second term, Trump signaled that he intended to reverse Biden’s denial of the project.

But few observers anticipated the president’s order this week. It responded to an appeal by AIDEA under a little-known section of the 1980 Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act — a provision that, before Monday, a president had never invoked, said Psarianos, the attorney who’s fighting the road in court.

AIDEA’s 92-page appeal was filed in June, without any public notice. It was drafted by Christopher Mills, a high-profile conservative attorney who’s worked under contract for AIDEA and once clerked for U.S. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas.

Trump’s 27-page decision approving the appeal declared that the road would “positively and significantly impact the national-security interests of the United States.” At the Oval Office on Monday, the president described the project as a “very, very big deal from the standpoint of minerals and energy.”

Trump’s announcement came alongside news that the U.S. government would take a 10% stake in one of the mining companies, Trilogy Metals, that would benefit from the road.

That small Canadian firm holds a 50% interest in Ambler Metals, which is seeking to develop a pair of copper, zinc and cobalt deposits in Northwest Alaska, near the end of the state’s proposed road. Those minerals, the project’s supporters say, are needed to support the global transition to renewable power and to meet growing demand for energy from companies developing artificial intelligence.

Trilogy’s stock rose more than 200% overnight, sending the company’s value past $1 billion — a dramatic sign that investors viewed the news favorably.

Fraught relationship with landowners

But others noted that the Trump administration, the state and the mining companies pushing the project still have major hurdles to clear before the road can be built.

A central challenge is that AIDEA has spent the past few years feuding with two Alaska Native corporations that own land that the road would cross. The corporations would likely need to endorse the proposal before construction starts.

The corporations, NANA and Doyon, have generally supported resource extraction.

NANA, owned by more than 15,000 Indigenous shareholders with ties to Northwest Alaska, has a partnership with the operator of the massive Red Dog mine, which sits on the corporation’s land. It also has partnered with Ambler Metals on that company’s mining projects in the region.

But both NANA and Doyon have publicly criticized AIDEA’s approach to the Ambler Road. Saying the agency wasn’t properly considering local interests, both ultimately chose to discontinue permits that had allowed AIDEA to conduct preparatory work on corporate lands.

Doyon, owned by more than 20,000 Native shareholders with ties to Interior Alaska, did so in 2023. The company’s chief executive said at the time that AIDEA had not advanced a deal “to ensure the impacts of the project or the mining district are mitigated by benefits to our corporation and its shareholders.”

NANA followed suit last year, saying AIDEA had insufficiently addressed subsistence protections, community benefits and other issues, including concerns about access to the road. While project boosters have said traffic would be restricted to mining-related vehicles, some Northwest Alaska residents worry the road could be opened to the public and bring an influx of urban hunters and fishermen to traditional subsistence areas.

In recent months, though, it appears the state has redoubled efforts to capture the corporations’ support.

In July, Gov. Mike Dunleavy sent a letter to the boards of NANA and Doyon saying he shares a “desire for limited and controlled access along the route, and to protect and support the caribou, fish, and other vital resources that are paramount to subsistence lifestyles and your traditional way of life.”

The same month, Dunleavy’s chief of staff flew to Kotzebue for a meeting with NANA’s board of directors, according to his public schedule.

Then, late last month, AIDEA’s board authorized its staff to enter into a non-binding memorandum of understanding with landowners along the haul route — an apparent reference to Doyon and NANA.

AIDEA would not answer questions about the potential agreement or its negotiations with the corporations. The two corporations also declined to comment directly on their discussions with the state.

Responding to the news this week, NANA’s president and chief executive, John Lincoln, said in a prepared statement that the corporation “appreciates the Trump administration and Gov. Dunleavy’s support for economic development in Alaska and their work towards stabilizing the federal permitting process.”

But, he added, NANA’s position “has not changed.”

It will be reconsidered only “if and when our established criteria are satisfied, in consultation with shareholders, local communities, and other stakeholders,” Lincoln said.

Doyon, meanwhile, “remains an engaged stakeholder” in the road project, a company spokesperson, Sarah Obed, said in an email. She declined to say if the corporation supports or opposes the road.

Burgum, the interior secretary, said at the Oval Office announcement that “there will be collaboration with the Native Alaskan corporations” in terms of how the road is built and used.

In an email to Northern Journal, a Department of Interior spokesperson declined to elaborate on the secretary’s assertion that road construction would begin next year.

Who will pay?

Even if the road gets permitted and Doyon and NANA enter into a new agreement with AIDEA, the agency would still need to raise hundreds of millions of dollars to pay for building the road.

AIDEA has estimated that construction would cost some $350 million, though other estimates are significantly higher. A Biden administration projection was nearly double that amount.

State officials envision a two-lane gravel toll-road, with access restricted to mine-related traffic. AIDEA has said it would borrow money to pay for construction and then charge mining companies fees to use the road, similar to how the Red Dog mine’s access road operates.

AIDEA would then use the road fees to pay off the debt, and potentially generate a profit.

To borrow enough cash to pay for the whole project, AIDEA would need approval from the Alaska Legislature. And that might be a tough sell, said Sen. Scott Kawasaki, a Democrat from Fairbanks who chairs the Senate State Affairs Committee, which has oversight of AIDEA.

“There's so much uncertainty” with the project from a financial standpoint, Kawasaki said in a phone interview.

Typically, construction of a mining toll road like Ambler wouldn’t start until the companies that expect to use it have secured the major permits for their mines and are ready to build them, said Bob Loeffler, an industry consultant and research professor of public policy at the University of Alaska Anchorage’s Institute of Social and Economic Research.

None of the companies with deposits in the Ambler district are at that point, so investors likely wouldn’t be ready to loan money to build the road, Loeffler said.

Ambler Metals controls the two most advanced prospects — Arctic, on state and private land, and Bornite, on land owned by NANA. The company has not applied for the major permits required for mine construction at either site, and it has yet to release a detailed study of Bornite’s economic feasibility, a process that usually takes a few years. The major permits, if the company secures them, are also likely to be challenged in court by conservation groups.

A new investor

Trilogy, the Vancouver-based company that owns half of Ambler Metals, hinted in a news release that its new investor — the U.S. government — could help the road project raise the needed money.

The Pentagon, which is now set to own 10% of Trilogy and appoint a new member of the company's board, will work to “help facilitate financing required for the construction of the Ambler Road in coordination with the state of Alaska,” the company said in a release this week.

A Trilogy representative did not respond to a request for further comment.

The federal government’s direct investment in a mining company is nearly unprecedented in recent history. But it aligns with other recent deals announced by the Trump administration aimed at expanding domestic production and reducing dependence on foreign suppliers. Those include investments in Lithium Americas, a company developing a mine in Nevada, and Intel, the American semiconductor manufacturer.

Kaleb Froehlich, Ambler Metals' managing director, declined to comment on how the government’s new stake in Trilogy might affect Ambler’s operations or permitting timelines.

Critics of the proposed road questioned the Trump administration’s use of taxpayer dollars to buy shares of a small Canadian company in an industry, mineral exploration, that’s famously risky for investors.

“We're still trying to work out how it's putting America first to invest in a foreign mining company to make it harder for Americans to live subsistence lifestyles in that region,” said Jim Adams, senior regional director at the National Parks Conservation Association, a group opposed to Ambler.

Froehlich, the Ambler Metals official, said his company is seeking to create local jobs and contribute to the economy of the region around the mining prospects — known as the Upper Kobuk — while also protecting subsistence and the environment.

“We believe any future mining in the Upper Kobuk must have lasting support from the people who live there, and we won’t move forward without it,” Froehlich said in an email to Northern Journal. “Our focus remains on advancing these projects safely and responsibly, in close partnership with NANA and the local residents.”

Correction: The Arctic mining prospect is on a mix of state and private land, not solely state land as the story initially said.

Curious to know more about the Ambler Road project and the issues it presents in Northwest Alaska? Northern Journal Publisher Nathaniel Herz, along with Anchorage Daily News photojournalist Loren Holmes, traveled to three villages in the region and helicoptered to the Bornite mining camp in 2021. Here's their dispatch.