A major new Arctic oil field prompted a deal to protect caribou. Then Trump officials backed out.

In December, the Interior Department scrapped an agreement with the village of Nuiqsut to restrict oil development near important caribou grounds. Now, the village is suing.

As oil giant ConocoPhillips forges ahead with construction of one of Alaska’s largest oil fields in decades, a new battle is emerging over a deal to protect a nearby caribou herd from the development.

After approving the Willow project three years ago, the Biden administration quietly signed an agreement with the nearby Iñupiaq village of Nuiqsut.

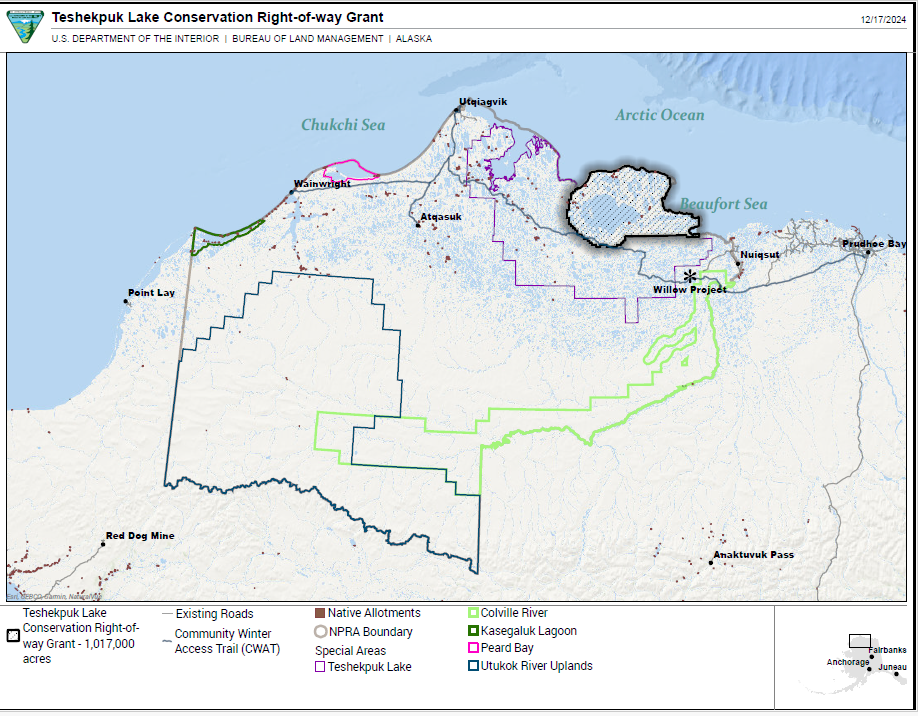

The deal gave leaders of the village power to regulate development across some 1 million acres of caribou habitat near Teshekpuk Lake — one of the most ecologically sensitive areas in northern Alaska and an important source of traditional foods about 50 miles northwest of Nuiqsut.

But now, after a sharp reversal by the Trump administration, the agreement’s fate is in the hands of a federal judge.

Late last year, Trump officials abruptly backed out of the deal, saying it undermined federal policy seeking to boost oil production in the federal reserve where both Willow and Teshekpuk Lake are located.

The move has sparked strong pushback from local leaders. Nuiqsut last month filed a lawsuit challenging the decision, saying it came without prior notice and threatens the village’s subsistence traditions.

Abandoning the agreement “jeopardizes decades of collaboration with local communities,” the village, represented by law firms in Anchorage and Washington, D.C., said in its January legal complaint.

The dispute comes amid a flurry of industry activity on the North Slope and near Nuiqsut, in particular.

Recent oil discoveries have led to a flood of investment and construction in the area, including Willow and another major oil field, Pikka, that’s being built by an Australian company. Meanwhile, ConocoPhillips is pushing a separate project to pump oil just two miles away from the village, within clear view and potentially earshot of Nuiqsut’s homes.

The Trump administration, meanwhile, is keen to open more of the region to drilling. It just announced a new oil and gas lease sale across more than 5 million acres in the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska, an Indiana-sized region of wild tundra, wetlands and foothills west of Nuiqsut.

Open to bidding are some of the very spots Nuiqsut and the Biden administration agreed to protect, near Teshekpuk Lake and the calving grounds of the Teshekpuk Lake caribou herd.

“A carefully crafted balance”

Teshekpuk Lake, some 25 miles long, is the largest lake on the North Slope, and it has unique importance across Alaska’s North Slope, including in Nuiqsut, where many Iñupiaq residents still practice subsistence lifestyles.

Located near the Beaufort Sea coast between Nuiqsut and the North Slope hub town of Utqiagvik, the lake is surrounded by wetlands and tundra that draw tens of thousands of migratory birds each year. Teshekpuk also provides ideal habitat to its namesake caribou herd, which numbers some 60,000.

Iñupiat not just in Nuiqsut but in other North Slope communities, including Utqiagvik, Atqasuk and Anaktuvuk Pass, have long hunted and depended on the Teshekpuk herd.

“That is where most of the caribou are coming from,” said George Sielak, president of Kuukpik Corporation, Nuiqsut’s Indigenous-owned village corporation.

Given its ecological and cultural value, the Teshekpuk Lake area has been the focus of conservation efforts for years. Aside from a few old exploration wells and seismic surveys, the area has seen little oil exploration.

But ConocoPhillips has been steadily moving in the lake’s direction over the past 20 years, as the industry’s roads, pipelines and drilling rigs spread westward from Prudhoe Bay.

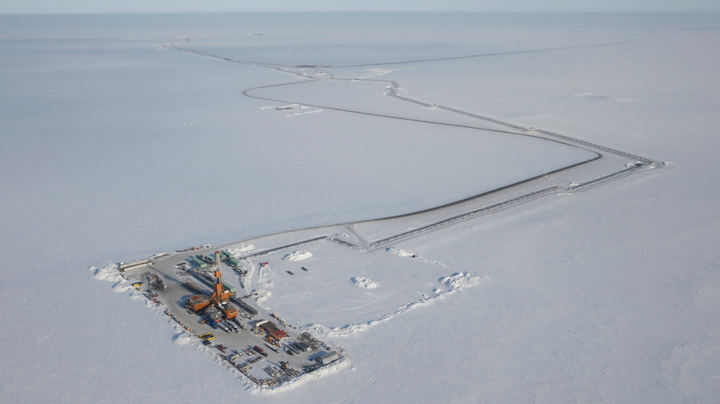

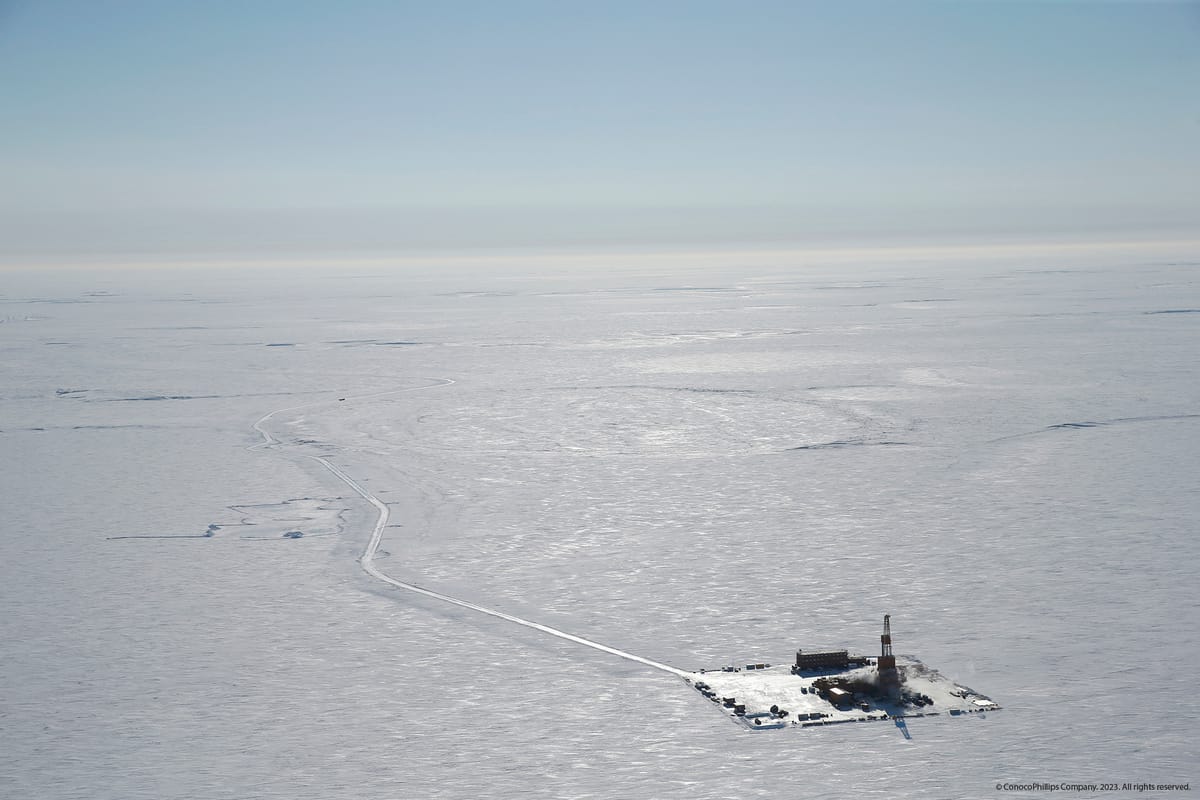

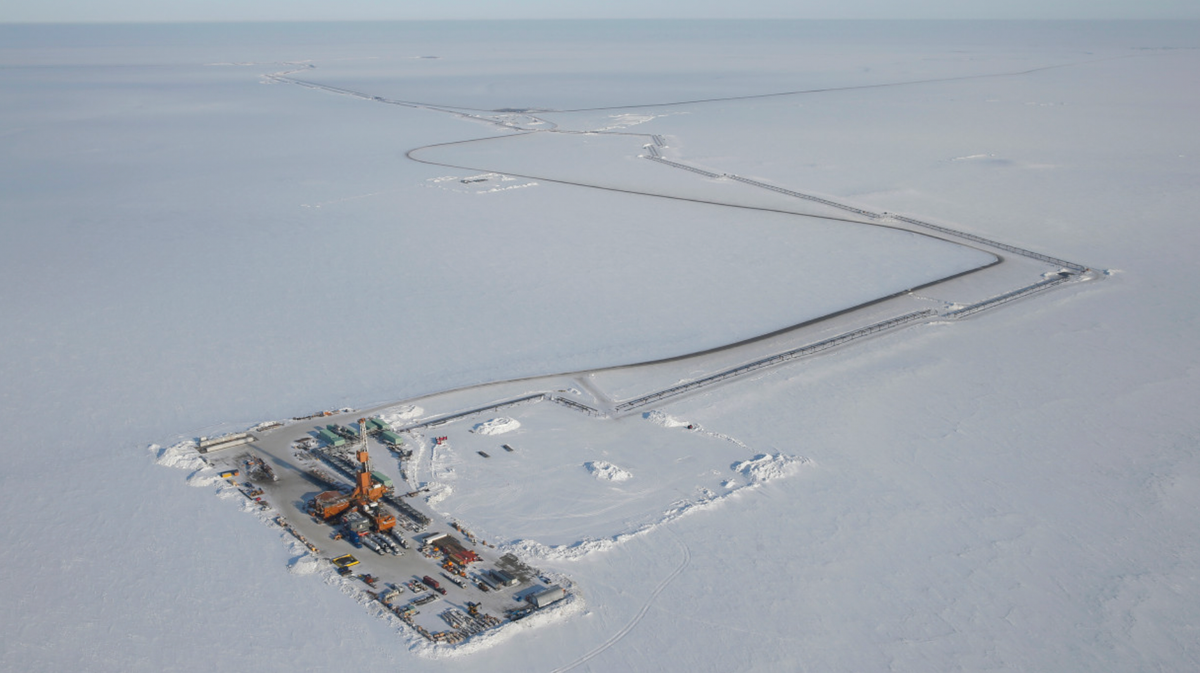

The Willow project will be closer to Teshekpuk Lake than any other major onshore development. It sits about halfway between Nuiqsut and the lake, within a caribou migration corridor and not far from the main caribou grounds.

Willow is nearly half built and on track to start pumping oil in 2029, Andy O’Brien, ConocoPhillips’ chief financial officer, said in a recent corporate earnings call.

ConocoPhillips executives have said the oil field could act as a hub for further development in the petroleum reserve, where the company is planning extensive exploration this winter.

The industry’s westward expansion has provoked mixed feelings in Nuiqsut.

Oil pays for schools and government services and is the backbone of the local cash economy. But when ConocoPhillips first proposed Willow several years ago, local officials, including some who historically supported the industry, feared that it would harm caribou.

Those concerns — and a lawsuit from conservation groups — ultimately led ConocoPhillips and federal officials to shrink the scope of the initial project proposal and make a number of changes to it.

One of those changes emerged in response to a suggestion from Kuukpik. It involved a permit provision directing the federal Bureau of Land Management to explore durable protections for Teshekpuk caribou, whether through co-management with local governments or other legal avenues.

Those protections ultimately took the form of a conservation area around the lake, where BLM, in a rare move, gave Nuiqsut ability to regulate oil and gas activities. That power was to be held by Nuiqsut Trilateral, a nonprofit made up of the village’s tribal and municipal governments, plus Kuukpik.

The agreement didn’t give Nuiqsut title to the land, but rather the rights to use it for subsistence and to limit development there until Willow stopped operating.

Although the deal got little attention relative to the Biden administration’s broader decision on Willow, some local officials viewed it as a critical tool to offset the oil project’s impacts.

“This was a carefully crafted balance,” said Andy Mack, Kuukpik’s Anchorage-based chief executive.

The more oil drilling pads near the village, and the bigger the operations, “the more impacts,” added Sielak, Kuukpik’s president.

“It’s in our backyard,” he said. The deal with the BLM, Sielak added, gave Nuiqsut “an assurance that our caribou could be protected.”

A new court battle

About a year after the Teshekpuk agreement was signed — and after President Donald Trump took office — Nuiqsut officials received a letter from Kate MacGregor, the new U.S. interior deputy secretary: The administration had decided to cancel the agreement.

Over nine pages, MacGregor explained her agency’s view that the protections were “improperly issued.” In last year’s budget bill, she wrote, Congress required oil and gas lease sales across the federal reserve encompassing Willow and the caribou grounds. And the White House, she added, has directed her agency to maximize oil production in the reserve.

Critics of the administration’s decision have noted that Congress, in the 1976 legislation that still governs the reserve, called for a balance. The bill says oil exploration should be done in a way that ensures the “maximum protection” of subsistence and other values around Teshekpuk Lake, and in other ecologically and culturally sensitive areas.

In 2021, U.S. District Court Judge Sharon Gleason determined that the first Trump administration failed to consider that directive when it initially approved the Willow project a year earlier, and Gleason halted the development.

In 2023, the Biden administration and ConocoPhillips agreed to a scaled-down version of Willow, which included the locally-backed provision calling for durable protections for Teshekpuk caribou.

In a legal ruling allowing the amended project to proceed, Gleason explicitly cited the new caribou mitigation measure — though she also said Congress “clearly envisioned” that the broader Teshekpuk area would be developed.

MacGregor, in her letter to Nuiqsut, said that companies have shown interest in conducting "exploration activities" in the conservation area as soon as this winter. “Expeditious cancellation is necessary to ensure these activities can proceed without delay,” she said.

She said that the area around Teshekpuk Lake has some of the “highest potential” for oil and gas in the 23-million-acre petroleum reserve — though companies would have to drill to know exactly how much oil and gas is sitting there.

An Interior Department spokesperson declined to elaborate, citing the pending litigation.

There’s limited public geologic data from around the lake, according to Dave Houseknecht, former U.S. Geological Survey petroleum geologist and North Slope oil expert.

The exploration results that do exist — and that are available to the public — don’t indicate the presence of large oil deposits, Houseknecht added.

There have been no lease sales around Teshekpuk Lake in recent years that would provide an indication of industry interest in the area.

And ConocoPhillips has actually abandoned holdings near it. Following the Biden administration's approval of a scaled-down Willow, the company gave up 68,000 acres of leases, mostly at the northern edge of the project toward Teshekpuk Lake.

That acreage is now being re-offered in the Trump administration’s upcoming lease sale, scheduled for March 18.

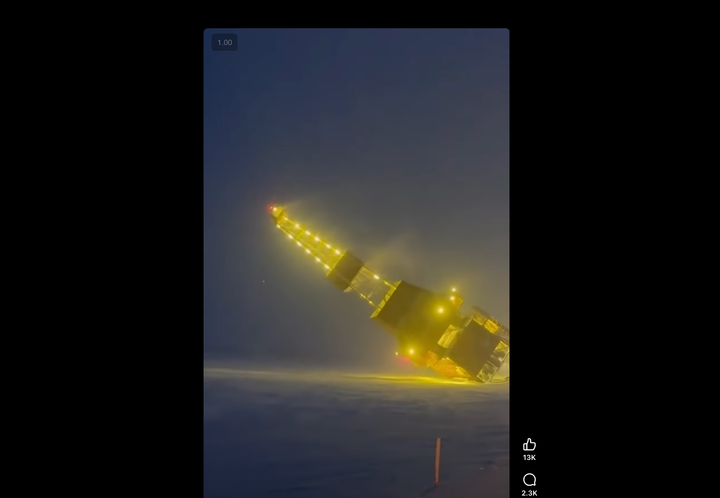

ConocoPhillips, meanwhile, is working around the recent toppling of a huge drill rig and pushing ahead with plans to drill exploratory wells and to do a seismic survey in the federal reserve this winter. That work will be well south of the disputed conservation area.

The company has stayed quiet about Nuiqsut’s agreement with the feds, and the interior department’s decision to cancel it.

A company spokesperson declined to comment on the cancellation, citing the lawsuit.

Reporting like this takes time and money. Northern Journal's primary revenue source is contributions from readers. If you're already a member, thank you. If not, we'd be grateful if you'd consider a voluntary subscription.