With gas crunch looming, Alaska's utilities won’t get big wind before tax credits expire. Here’s why.

One utility leader points to private developers and the Trump tax bill. But advocates say utilities share some of the blame.

For years, urban Alaska utilities have been studying large-scale wind farms that could help break the state’s dependence on natural gas power — encouraged by the potential for hundreds of millions of dollars in tax credits from the federal government.

Next summer, however, those tax credits will largely disappear for projects that haven’t started construction, a consequence of the tax bill that President Donald Trump signed in July.

Clean energy advocates, and U.S. Sen. Lisa Murkowski, had said they hoped that Alaska wind projects could still advance in time to qualify.

But in recent weeks, board members and executives at the cooperatively owned utilities have acknowledged that the timeline now appears too short — which means any large-scale projects will now have to be built without the generous federal subsidies, or wait to see if Congress reestablishes a more favorable tax regime.

[From the Anchorage Daily News: Murkowski feels ‘cheated’ by Trump administration actions against wind and solar projects]

Critics say the absence of major new renewable projects will leave the state dependent on imported, liquefied natural gas and could make consumers vulnerable to price spikes.

“There’s an argument to be made that these electric cooperatives, whose boards have a fiduciary responsibility to the member-owners, have really frittered away one of the greatest opportunities they’ve ever had to deliver hundreds of millions of dollars of value to their members,” said Phil Wight, an energy historian and professor at University of Alaska Fairbanks. “At the highest level, I think that’s a fair argument.”

Since Congress approved expanded tax credits in 2022, Alaska has seen no large-scale wind or solar projects begin construction, while other states like Wyoming and Texas have received billions of dollars in clean energy investment.

At a recent meeting, board members at Golden Valley Electric Association, the utility that generates power for Fairbanks area residents and mines, rejected a developer’s bid to advance a large-scale wind farm on a schedule driven by the expiring tax credits. Utility officials said there was still too much uncertainty about final pricing and whether the project could capture the credits.

Meanwhile, officials at Anchorage-based Chugach Electric Association, the state’s largest power utility, say that another large wind project they’ve been studying with the same developer also won’t be ready to start construction in time to qualify for the credits.

Jim Nordlund, a Chugach Electric Association board member, said that if the Anchorage-area project had captured the credits, it was still far from clear that it could have provided power more cheaply than his utility’s existing natural gas plants.

That’s even assuming prices will rise when local fuel supplies dry up and utilities begin importing liquefied natural gas in the next few years, added Nordlund, a self-described clean energy advocate.

The price of renewable power generally, he said, “is really high.”

Alaskans who are frustrated about the pace of wind and solar development shouldn’t blame the urban utilities, Nordlund added. Private companies, not the utilities themselves, have been advancing projects that failed to materialize, he said, and politics also played a big role.

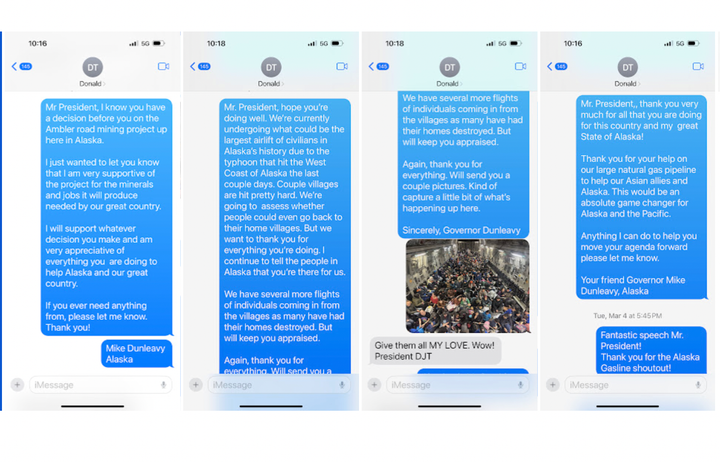

“If you want to blame anybody for this, it would be that big bad bill. That’s what Trump wanted to do, and it worked,” Nordlund said. “It shut down, at least for the time being, our projects.”

But renewable energy boosters say that the urban utilities deserve at least some share of the blame for not advancing projects more urgently while the tax credits were in place.

The utilities could have developed large wind developments themselves, those advocates argue — or they could have done more to create a stable and attractive market for private developers.

“The utilities are uniquely bureaucratic and expensive in their own self-development. And they’re uniquely bureaucratic and obstinate and slow if a private company is developing,” said Ethan Schutt, who formerly managed the energy assets of an Indigenous-owned regional corporation.

Advocates say utility leaders have also failed to endorse, and in some cases outright opposed, legislation proposed multiple times in recent years to establish renewable energy quotas — which they say could have encouraged more private developers to work in the state.

Large-scale power projects “need to be thoughtfully implemented,” Natalie Kiley-Bergen, energy lead at an advocacy organization called Alaska Public Interest Research Group, said in an email.

“Had more progress been made in the last five years — even the last 15 years — to create a competitive market environment with regulatory and economic certainty for these projects, we could have seen responsible project commitments regardless of federal changes,” Kiley-Bergen said. “Not capitalizing on these tax credits is a product of years of moving slowly on the tremendous opportunities to diversify our energy generation."

A risk of price spikes?

After its initial discovery in the 1950s, Cook Inlet, the offshore and onshore petroleum basin southwest of Anchorage, produced huge quantities of natural gas.

There was enough fuel to generate not just the vast majority of the region’s electric power, but also to supply plants that produced fertilizer and exported gas in liquefied form to Asia.

But those plants have now closed amid Cook Inlet production declines. And for more than a decade, the urban electric utilities have been contending with risk that gas supply won’t be adequate to meet demand.

[Offshore in Cook Inlet, a 'silent economy' hunts for gas to keep Alaska running]

Generous state tax credits temporarily approved by lawmakers in 2010 helped stimulate new drilling, but only temporarily, and they were subsequently repealed. Three years ago, Cook Inlet’s dominant producer, Hilcorp, warned utilities that they should not expect new long-term commitments of gas when their existing contracts expire in the coming years.

Clean energy advocates say that Alaskans’ dependence on gas-fired power — Chugach Electric Association generates 87% of its power from the fuel — makes residents vulnerable to both supply disruptions and fluctuations in price.

The utilities have responded to the looming local gas shortfall with plans for new infrastructure that could offload imported liquefied natural gas, known as LNG, shipped from Canada or the Gulf of Mexico.

But unlike gas from Cook Inlet, which producers have long sold at a fixed cost, utilities would likely have to buy LNG at rates that swing with the market, similar to the price of oil, according to Antony Scott, an analyst at the Renewable Energy Alaska Project advocacy group who once studied petroleum pricing for Alaska’s state government.

Given the risk of price spikes that could translate into higher electricity prices for consumers, diversifying with new wind and solar development should be a “no-brainer,” Scott said.

“It's just like an investment portfolio. Do you want to invest only in Tesla?” Scott said. “A rational, prudent investor would have a diversified portfolio.”

Scott’s advocacy group, and others in Alaska, have pushed the utilities to diversify, in part through lobbying for the creation of the renewable energy quotas.

They cite analyses like a study released last year by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, which found that new renewables would be cheaper than burning gas in existing plants and, by 2040, could meet up to 80% of demand.

“Ratepayers in Alaska have been saying, for a long time, that we need renewable energy projects here at home, and we need to be capturing energy here at home,” said Alex Petkanas, clean energy and climate program manager at the Alaska Center conservation group. “This is not something that is a surprise — that our local natural gas supply is ending, and we need to replace that with new generation.”

A rejected agreement

Utility staff and board members agree that they need to diversify away from gas, with the chief executive of Matanuska Electric Association saying in 2022 that it was "untenable" to continue generating 85% of power from one type of fuel.

Chugach Electric Association aims to cut its carbon emissions in half by 2040, which would likely require sharp reduction in its use of natural gas. And a Golden Valley Electric Association strategic plan approved last year calls for the utility to finalize agreements with private developers to bring on "large-scale wind resources" at prices that will lower members' power costs.

None of those utilities have moved to build major wind or solar farms themselves; instead, they’ve looked to private companies to do the construction and sell the power onto the grid.

Just one firm, Longroad Energy, has advanced large-scale wind projects on a timeline that could have qualified for the expiring tax credits. One is outside Anchorage in Chugach Electric Association’s region, and one is outside Fairbanks, in Golden Valley Electric Association’s region.

The Fairbanks area project, known as Shovel Creek Wind, could produce one-third of the power consumed by Golden Valley’s members — and even generate more than 100% of their demand at certain times, depending on the size of the development, said Golden Valley’s chief executive, Travis Million.

But at a July board meeting, Golden Valley’s board members rejected an agreement that Longroad had proposed to keep the project on a timeline to qualify for the credits.

Golden Valley, said Million, still needed more time to finish a study of how much it would have to spend on infrastructure upgrades and its existing fossil fuel plants in order to accommodate power from the new wind project. Utilities must balance swings in power production that stem from the natural variability of wind.

“Without having that step done, there’s just so much uncertainty about the cost. And not knowing what that end result would be to our members, we just could not commit,” Million said in a recent interview. The details of the proposed agreement — including Longroad’s estimated pricing — are confidential under a non-disclosure agreement.

There was additional uncertainty, Million added, about whether the Trump administration, which has been hostile to wind power, would grant the credits even if Shovel Creek advanced on the required timeline.

But Million also acknowledged that the utility could have done more work earlier to speed up the process.

“We should have done a lot of these studies on the front end, to really understand sizing and needs on Golden Valley’s system, before we really started going down this path with trying to find developers,” Million said.

Longroad, through an Anchorage-based consultant, declined to comment. Million said that Golden Valley plans to finish its study and hasn’t ruled out advancing Shovel Creek on a slower timeline than Longroad’s proposal.

The utility is also studying a substantial, if smaller, wind project that could still qualify for the tax credits.

“We have to take control”

In Anchorage, meanwhile, officials with Chugach Electric Association said that Longroad’s work on the nearby Little Mount Susitna wind project slowed as the company focused on advancing Shovel Creek.

The developer, said Chugach board member Nordlund, isn’t ready to make the initial investment in Little Mount Susitna and couldn’t do the continuous work required in order to take advantage of the tax credits — though the utility, he added, hasn’t given up on the project moving forward in the future.

Nordlund ran for the Chugach board in 2023 as an advocate for wind and solar, saying then that “the time to act on renewables is now.”

But he said in a recent interview that there’s “misinformation” circulating that utilities are dismissing proposed wind and solar developments that would generate power more cheaply than natural gas, when that’s not clearly the case.

Chugach has its own non-disclosure agreement with Longroad that Nordlund said bars him from getting specific about prices.

But speaking generally, he added, Alaska is a tough market for private developers, compared to the Lower 48 and foreign countries where they otherwise might invest.

Construction costs in Alaska are higher given the remote setting, harsh environment and lack of contractors competing for business, Nordlund said; the relatively small consumer base also means that developers can’t capture economies of scale.

“I think we need to create a better climate for independent power producers to do business in Alaska,” Nordlund said. The stalled legislation to establish renewable energy quotas could have helped, he added, by giving those private developers more certainty that the utilities were “serious” about bringing on wind and solar projects.

“More could have been done,” he said.

Nonetheless, Nordlund said he thinks the inherently "conservative" culture of Alaska’s utilities is changing, with executives increasingly open to accommodating wind and solar power.

Chugach officials say the utility is still pursuing renewables and remains open to proposals from developers — though they are now refocusing on more modest projects that they can advance in-house, at least in the early stages. Viable projects could then, potentially, be handed off to private developers.

At meetings in recent weeks, board and staff members have discussed a small-scale solar farm that Chugach is studying at the site of one of its existing gas power plants on the far side of Cook Inlet.

They’ve also heard a presentation from a consultant who is examining potential sites for new hydroelectric development, though those projects would face a lengthy permitting process.

“We now have to take control and get in the lead,” Dustin Highers, Chugach’s vice president for corporate programs, said at a recent board meeting.

But some experts like Wight, the energy historian, remain skeptical that those efforts will end up displacing very much gas, with the exception of the smaller wind project in the Fairbanks area that he said could still “make a real difference.”

Pursuing smaller projects with better coordination between regions could be a better strategy, Wight said. But failing that, he said he expects utilities to largely continue their dependence on natural gas — whether through imported LNG, or through a proposed pipeline project from Alaska’s North Slope that’s struggled to secure commitments from investors.

“They’re going to dabble a little bit in renewables here and there, and then they’re just going to hope for cheap gas,” Wight said. “As a state, we’ve been so oil- and gas-dependent for so long that I do think there’s a cultural barrier there, to bring in the new folks who want to think differently.”

Northern Journal runs on reader support — voluntary paid memberships make up the majority of our revenue. Join if you can; if you already are a member, thank you.