A feud is escalating over Big Oil’s plans to protect Prince William Sound from another spill

The city of Valdez and the owner of the trans-Alaska pipeline are locked in a dispute over environmental protections at the state’s crude oil shipping port.

Every day, millions of gallons of oil move from the Arctic through the trans-Alaska pipeline to the small coastal town of Valdez, 600 miles away.

There, high above the waters of Prince William Sound, the oil is piped into massive storage tanks, where it sits until ships come to pick it up, typically bound for refineries in the Lower 48.

These tanks, and the risk they pose to the environment, are at the center of a new feud between the oil industry and Valdez’s city government.

City officials, through their attorneys, argue that aging environmental safeguards — part of contingency plans approved by state regulators last year — are no longer adequate to prevent stored oil from escaping the storage tanks and polluting the sound.

The consequences, they say, could be catastrophic, potentially involving a release of as much oil as the infamous 1989 spill that contaminated the sound when the Exxon Valdez tanker ran aground on Bligh Reef.

Any spill at the Valdez port "would have a huge impact on the citizens of Valdez, and on all Alaskans,” Jake Staser, an Anchorage-based lawyer representing the city, said in a phone interview.

Valdez’s economy is deeply intertwined with the oil industry, which sustains many of the town’s high-paying jobs and pays substantial local property taxes.

But the flare-up is the latest example of how the city’s interests have sometimes diverged from those of Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. — the business that operates the trans-Alaska pipeline and the Valdez Marine Terminal, the massive shipping complex where the storage tanks sit. Alyeska is owned by affiliate companies of Hilcorp, ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips, the state’s major oil producers.

The new dispute comes on the heels of lawsuits brought by city officials over oil-related property taxes and financial transparency, and a few years after a lengthy report questioned safety practices at Alyeska’s export site.

Alyeska, for its part, says the likelihood of a big spill is vanishingly small. And state regulators note that the company, as required by law, has extensive measures in place to prevent and respond to one.

But observers and watchdogs say they’re increasingly concerned about the integrity of some of the company’s infrastructure and its risk of failure.

An aging barrier against spills

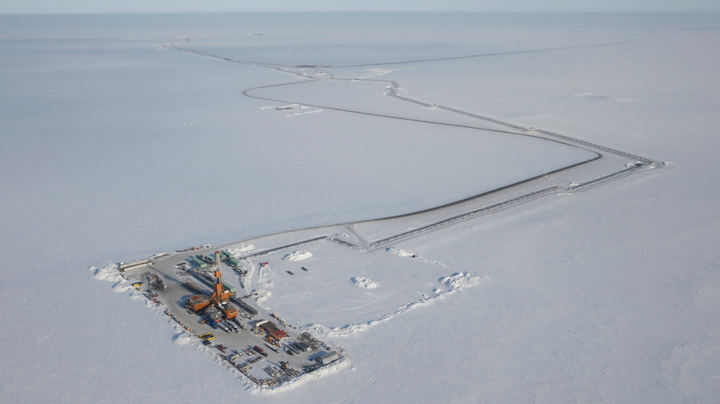

Alyeska currently uses 13 of the 18 tanks that were originally installed at the export terminal, and each can hold roughly 500,000 barrels of oil.

While they’re typically not all full at once, the site has the capacity to store more than 6 million barrels of crude — roughly one third of the nation’s daily petroleum use.

The current dispute is quietly playing out before regulators and an administrative judge — part of the state’s review of Alyeska’s contingency plan for spills at the export terminal. That plan is up for renewal every five years. Regulators re-approved it last year, and the city of Valdez contested that decision in March.

The contingency plan is expansive, filling three volumes with 1,000 pages. And Valdez’s appeal involves numerous issues, including Alyeska’s ability to detect leaks from its storage tanks and the company’s preparedness to respond to a spill.

One of the city’s primary concerns is a buried layer of asphalt that’s supposed to seal off the ground beneath the tanks from any oil that spills out of them, protecting groundwater and the Port Valdez fjord — an arm of Prince William Sound — from pollution.

The tanks sit in large dikes intended to keep spilled oil from leaving the site. Observers are less concerned about crude washing straight into the sound than it seeping into the ground through cracks in the asphalt, and potentially contaminating groundwater that flows into the ocean.

The asphalt liner was built at the same time as the tanks, in the mid-1970s. Since then, only a tiny fraction of it has been inspected for damage, according to documents submitted by the city to the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation.

In the small portion of the liner that’s been assessed, “pre-existing holes, cracks, and tears” and “numerous spills and leaks” have been detected, the city says. The status of the asphalt has long been a cause for concern among local industry observers.

Alyeska has inspected less than 1% of the liner in its 48-year history, the city said in one of its submissions to the state.

Its lawyers have called on the company to replace the liner with newer technology — or, at a minimum, to fully evaluate and repair it by 2027.

“Nobody really knows what the integrity of that liner is,” said Joe Lally, a Valdez resident who works with a local industry oversight group created after the 1989 spill, the Prince William Sound Regional Citizens’ Advisory Council.

None of the players involved in the dispute have said how much replacing the liner could cost. But it’s clear that it would be an enormous task: The asphalt is buried under several feet of soil and gravel, and it spans more than 50 acres, underlying all of the active tanks.

Alyeska has proposed a few different ways to inspect it for damage, including flooding the tank farm with water or searching for holes or leaks with an electric current.

State regulators at the Department of Environmental Conservation have yet to approve a comprehensive testing plan, though, and have repeatedly asked the company for additional information. They told Alyeska last month that its test “must produce results that [the department] can rely on to make a determination about the integrity of the entire liner” and said that details in the company’s proposal were lacking.

Earlier this month, the city asked the department to take more “expedient action” on the issue.

“We want to know where the leaks are, and to what extent leaks exist,” said Staser.

Citing the ongoing appeal, a Department of Environmental Conservation spokesperson declined to answer questions about the liner and Alyeska’s proposals to assess its effectiveness. He said that even as the department’s review plays out, Alyeska’s re-approved spill plans remain in effect and require prevention measures, response equipment and trained crews “to be in place at all times.”

Department staff "live and work in Valdez, which means our inspectors are regularly present at the terminal," said the spokesperson, Sam Dapcevich.

"During site visits, staff observe spill drills, verify response equipment readiness, and review day-to-day operations to ensure the terminal is meetings its contingency plan obligations," he said.

An Alyeska spokesperson, Michelle Egan, declined to comment specifically on the liner or the city’s assertions, citing the ongoing appeal.

A ‘nightmare scenario’

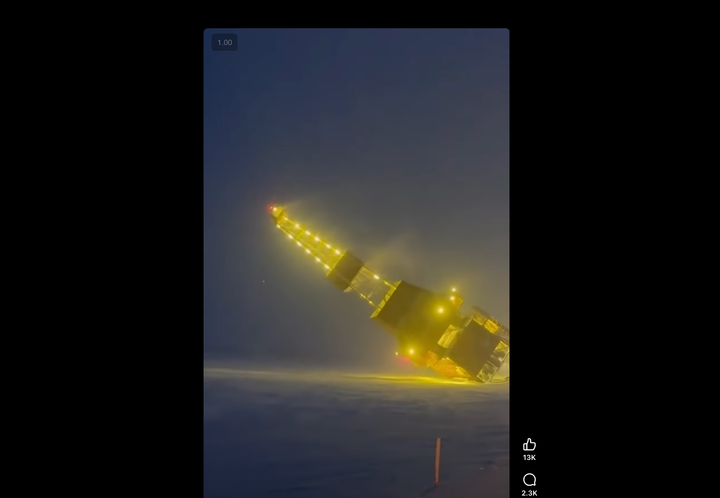

Alyeska’s prevention plan notes the potential for “the simultaneous failure of two tanks” in the same area, spilling between 500,000 and 900,000 barrels of oil — roughly two to four times the volume that the Exxon Valdez released.

But in other documents, Alyeska mentions a more realistic estimate of a worst-case scenario to be around 200,000 barrels, and not all of it would wind up in the water.

A large spill also might occur in a less obvious way, according to an Alyeska official, Andres Morales, who testified about the risk in a separate court case last year.

A slow leak in the bottom of one of the tanks could go undetected for months, possibly accumulating into a spill of tens of thousands of barrels of oil, Morales said.

That would be a “nightmare scenario,” he added.

“Corrosion, pinhole leaks terrify me because they happen and you're not aware they happened,” Morales said.

Alyeska, in its filings with the state this year, has said that a worst-case spill at the tank farm is exceedingly unlikely, estimated to occur roughly once every 100,000 years.

The tanks themselves are rigorously inspected, Egan, the company spokesperson, wrote in an email to Northern Journal.

Tanks are cleaned, inspected from the inside and re-coated with sealant every 10 to 15 years, and the exterior of each tank is subject to much more frequent inspections, Egan said.

She also said that a system of electric currents, known as cathodic protection, guards against corrosion in the floor of each tank.

Alyeska has a “substantial amount” of response equipment in the event of a spill, Egan added. That includes trucks and vacuums to suck up any oil that spills on land, as well as booms and barges to recover oil in the water.

“Protecting Prince William Sound is personal — many of us live here,” Egan said. “We’re committed to working productively with regulators, stakeholders and our neighbors to safeguard the place we all call home.”

Lally, with the watchdog group, spoke highly of Alyeska’s ability to respond to spills, including the extensive equipment and training the company has developed in the years since the Exxon Valdez disaster.

“They’re the gold standard for response,” he said.

But the aging asphalt beneath the company’s tank farm, he said, is a different story. .

“If something, God forbid, ever happens to one of the tanks, and they were to lose a significant amount of oil,” Lally said, “we want to make sure that secondary containment liner is going to act as designed and hold the oil long enough for them to clean it up.”

Correction: Eighteen tanks were originally built at the Valdez Marine Terminal, not 22, as the story initially said.

In-depth journalism like this takes time and money. Northern Journal runs primarily on voluntary memberships from readers; if you want to see more stories like this, please consider subscribing. If you're already a subscriber, thank you.