Alaska’s governor said he texts Trump. I asked for copies.

"Give them all MY LOVE. Wow!" Trump said in one of his messages to Gov. Mike Dunleavy, who says he tries not to abuse his access to one of the most powerful men in the world.

A couple of months ago, I was reporting on the typhoon that hit Western Alaska and stopped by a news conference convened by Gov. Mike Dunleavy.

I was there to ask him about long-term plans for protecting vulnerable coastal villages. But the governor diverted my focus by talking about Donald Trump and the president’s concern. The previous week, Dunleavy said, “I was texting him at one in the morning, his time, about this disaster.”

A normal person probably wouldn’t react strongly to this statement; after all, the two Republicans are politically allies and have something of a bromance, with Trump calling Dunleavy his “friend” and advancing a slew of pro-development actions that align with the governor’s agenda.

But my brain is tuned to resonate at a very specific frequency: that of Alaska Statutes 40.25.100 - 40.25.295, otherwise known as the Alaska Public Records Act.

Which is why Dunleavy’s comments grabbed my attention. The executive branch often uses various statutory exemptions and legal maneuvers to withhold certain correspondence and records — namely, asserting a “deliberative process privilege” to shield internal, unvarnished communications within agencies.

But because the president exists outside state government, that deliberative privilege, presumably, wouldn’t apply — offering me, potentially, a look at Dunleavy’s unvarnished communications with the leader of the free world. The next day, I requested copies of all of Dunleavy’s text messages with Trump since early this year.

Two days later, I was summoned to the governor’s office in downtown Anchorage to collect the response: four flash drives loaded with tens of thousands of messages between Dunleavy and Trump, detailing political machinations and covert activities to ward off Chinese influence operations inside Alaska. Working with reporters from the Anchorage Daily News, Alaska Public Media and the Nome Nugget, I reviewed —

Okay, yeah…no, that’s not actually what happened. Ten business days after making my request — the deadline under the public records act — I got an initial response: a legally authorized extension so that the state could “consult with legal counsel to ensure that protected interests of private or government persons or entities are not infringed.”

Fair enough, I thought — reasonable that Dunleavy’s office might want to be cautious about releasing texts to and from the president. I was less generous when, 10 business days later, I got my next response: an early morning email asserting that the state didn’t have to respond within any particular timeline because I was requesting not “public records” but “electronic services and products involving public records.”

Such requests, for electronic services and products, fall under a different area of the public records law, without deadlines.

“Text messages and the work required to provide them in a readable and transferrable format are computer-related: searching for, extracting, duplicating, and transferring texts require software,” Guy Bell, the employee in Dunleavy’s office who handles records requests, wrote in an email. “We will make every effort to respond within the next few weeks.”

I did not find this argument compelling. I responded to Bell half an hour later explaining that I thought this was a bad faith delay tactic and that such a legal position should have been asserted when I first made my request, not a month later. Please let me know by the end of the day, I told Bell, whether the state would reconsider this determination, or I would be considering my legal options. (This is reporter-speak for: I think you’re staking out an indefensible legal position, and if you stick to it, I’m gonna sue.)

The governor’s office did, in fact, reconsider its position, which I was informed was “out of courtesy” to me and “to avoid litigation.”

It obtained one more 10-day extension directly from Dunleavy’s attorney general, a process laid out in state regulations.

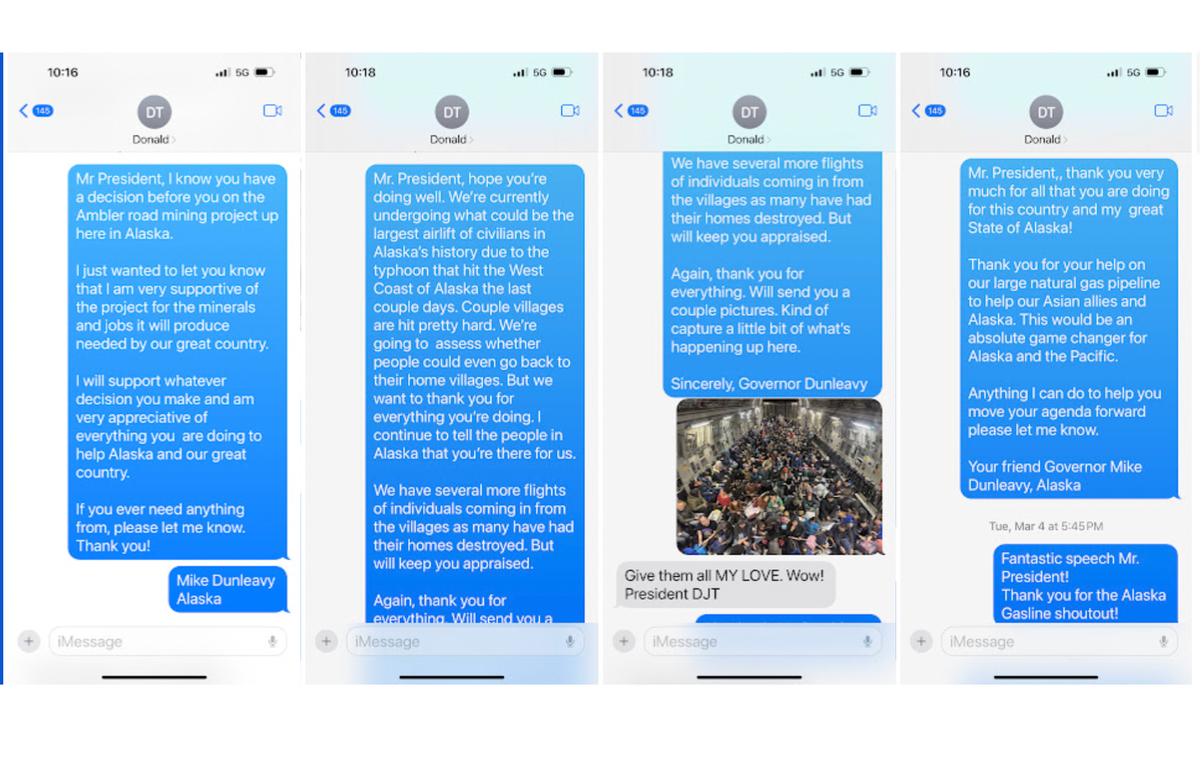

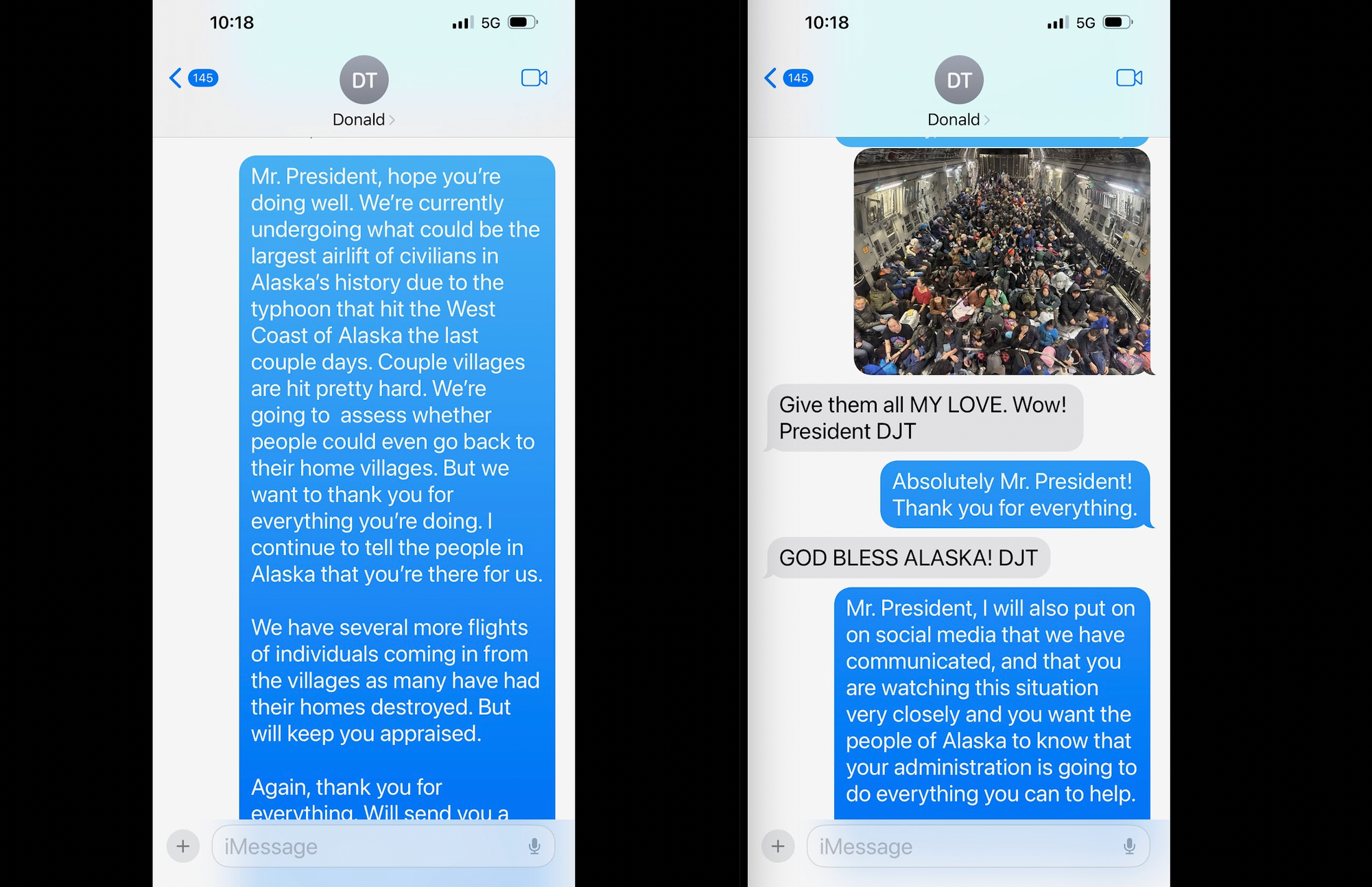

Then, last week, Bell sent me another email — this time, with attached screenshots showing the trademark blue and gray bubbles of iPhone messages. At the top: a “DT,” denoting the initials of the president of the United States. (Also at the top: an indicator showing that the governor of Alaska has 145 unread texts.)

There were just six substantive texts from the governor to the president, half of which were information about the typhoon and thanking Trump for the federal government’s response. Another message praised the president’s unofficial state of the union address in March — ”Fantastic speech Mr. President!” — and the other two were broad appeals about big proposed projects favored by Dunleavy: the Ambler mining road in Northwest Alaska, and the state’s massive natural gas export development.

"Mr. President,, thank you very much for all that are doing for this country and my great State of Alaska!” one said. “Thank you for your help on our large natural gas pipeline to help our Asian allies and Alaska. This would be an absolute game changer for Alaska and the Pacific. Anything I can do to help you move your agenda forward please let me know. Your friend Governor Mike Dunleavy, Alaska"

The screenshots showed just one set of responses from Trump, to the typhoon related texts and a photo that Dunleavy shared of evacuees crowded into a military transport plane. “Give them all MY LOVE. Wow! President DJT”, one read. “GOD BLESS ALASKA! DJT” said another.

Dunleavy agreed to talk with me briefly about his messaging relationship with the president.

Trump, Dunleavy said, gave him his phone number, and no, he was not going to share it with me. Dunleavy did not text with Democratic former President Joe Biden, he added; with Trump, “it’s great to be able to have a positive relationship with, arguably, the most powerful person on the planet that can make some good decisions for Alaska.”

“I try not to abuse or overuse the positive relationship,” he added. “He’s got lots going on, so I try not to bother him.” But, Dunleavy said, “whenever we’re dependent on the federal government for something,” like typhoon relief, “I wanted to give him a heads-up that that was happening.”

Even critics of both Dunleavy and the president acknowledge that the governor’s proximity to Trump, as shown by the texts, can advance Alaska’s interests in situations like the typhoon aftermath.

“I hate to praise Dunleavy, but this gives us the opportunity to say: We have the right person in the right place in the right time for this particular emergency,” said Anchorage Democratic Rep. Andrew Gray, who reviewed the text messages. “I don’t believe that Donald Trump is good for America. But if Donald Trump is the president, and our governor has this direct line of communication to him, I think that there are definite benefits to the state.”

I had one lingering question, though: whether I was really seeing all the messages that the governor and the president exchanged.

I’d heard that Dunleavy and Trump communicate fairly regularly; the messages that were released gave the impression of much rarer exchanges. But the screenshots, I noticed, also seemed fairly tightly cropped. And I know that in the past, the executive branch has withheld messages from me that fit my public records search terms but are deemed “transitory” or personal — which would allow them to exempt those records from their response.

The basis for that position is a Palin-era Alaska Supreme Court decision holding that public records, as defined in state law, are only those preserved or appropriate for preservation by agencies for their informational value, or as evidence of the way government functions.

“Not every record a state employee creates, and certainly not every state employee email, is necessarily appropriate for preservation” under the law guiding Alaska’s management of public records, Justice Bud Carpeneti wrote in his 2012 opinion.

In his email, Bell described the screenshots as “the records responsive to your request for all of Governor Dunleavy's text messages sent to or received from President Donald Trump.”

Notably, he did not describe the screenshots as “all of Governor Dunleavy's text messages sent to or received from President Donald Trump.” So, I emailed him back with a question: Were any messages between the governor and the president withheld on the basis that they were transitory or otherwise deemed to be “non-record communications”?

Bell's response: “As the public records officer for the office of the Governor, I have confirmed and assure you that we have provided you all the text messages related to state business.”

At that point, I called Bell and told him that I would describe his answer as not, actually, an answer to my question. He was very polite, but he did not share additional details.

Sure: I can accept, as a plausible argument, that it doesn’t make sense for the state to permanently archive and maintain every single email sent by every employee at a state agency.

But what about at the level of a chief executive-statewide elected official — for whom the personal, in fact, is often political? And what if a message doesn’t meet the state’s legal standards for preservation, but still exists because it hasn’t been deleted? Should the state not provide it to the public on what’s, effectively, principle? How can a member of the public contest the state’s assertion that a record is “transitory” or “personal” if agencies won’t even confirm that messages have been withheld, or how many have been withheld?

Those are all questions worth considering, I think, and questions that lawmakers should also be actively pondering. I asked Dunleavy for his opinion — if he thought the public should have access to all of his correspondence with Trump.

“If it touches on state business, we have laws in place that dictate that would be open to the public, which is the form of government we have. I don’t disagree with that at all,” Dunleavy said. But, he added, what about some hypotheticals: “If I text the president to say happy birthday, is that state business? Some would argue it’s not. If I text the president, ‘Good luck to [son] Barron [Trump] going to university,’ is that considered state business? I don’t think it is.

“You’re a reporter, and you want information, which is part of the job,” Dunleavy said. “But I think as a human being, you would also say to yourself, ‘Yeah, he’s probably right. Some of those things really aren’t state business.’”

Sorry, gov: I’m not a normal human being — I’m a guy who gets a kick out of badgering public agencies to adhere to meticulous legal standards for transparency.

It’s the other human beings out there — readers, lawmakers, the Alaska public — who can decide if the governor is right.

Northern Journal's primary revenue source is contributions from readers. If you're already a member, thank you; if not, please consider a voluntary subscription by clicking the button above.