An Alaska Native group was set to honor a Pebble mining official. Then came the backlash.

The controversy over a typically celebratory honor underscores the intense polarization over resource development in Alaska Native communities.

The First Alaskans Institute’s annual gala awards rarely get much attention outside of the black-tie fundraiser where they’re given.

The honors typically go to people whose work has aligned with the organization’s mission of advocating for Alaska Native communities, and they’re usually a cause for celebration, not controversy.

But this year, one of the awards has provoked intense pushback.

The high-profile Indigenous organization announced last week that an honor for non-Native people would be shared by John Shively.

Shively is a longtime player in Alaska government and political circles who helped lead and set up several prominent Native institutions.

He is also the chief executive of the company pushing the stalled Pebble mining project — a huge and contentious proposed mine that’s strongly opposed by many members of the state’s Native communities.

Pebble’s opponents quickly condemned the selection of Shively for the award. After the president of the First Alaskans Institute told him about the opposition, Shively declined the honor to “avoid harming” the organization, he said in a phone interview.

For the past week, First Alaskans Institute has been contending with the fallout, both from Pebble’s opponents and from supporters of Shively, who feel he was treated unfairly.

The institute is a nonprofit intended to advocate on behalf of the state’s Indigenous people. It was formed in 2000, spurred by a $20 million pledge from the oil industry.

Led by board members from around the state, the organization has long tried to straddle divergent interests within the Native community, and to work on unifying issues like cultural preservation and an annual gathering for elders and youth in Anchorage.

The response to Shively’s selection highlights how hard that job can be, particularly when tensions arise between pro-development and environmental interests — a conflict that sometimes shows up in the disparate missions of tribal governments and for-profit Alaska Native-owned corporations. The Alaska Federation of Natives, known as AFN, has contended with similar divisions in recent years, with both tribal and corporate members leaving the organization, though some have recently returned.

“Native people like those at First Alaskans and myself are kind of caught between the devil and the deep blue sea,” said Roy Huhndorf, a former AFN co-chair and former president of CIRI, the for-profit Native regional corporation for Anchorage and the surrounding area.

That tension, Huhndorf added, has existed since at least 1971, when Congress passed the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act that created the for-profit Native-owned corporations.

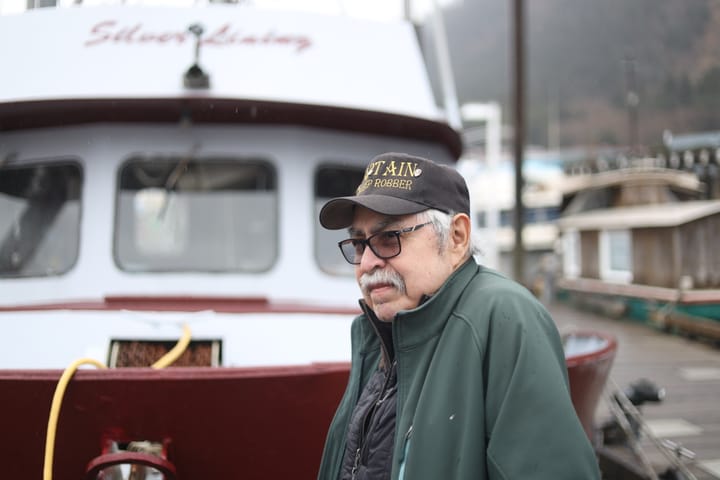

Shively’s work in Alaska dates back to the 1960s and has ranged widely across multiple industries.

He served as an executive at Northwest Alaska’s regional Native corporation, NANA, where he helped advance development of the massive Red Dog mine — a project operated by a multinational company on NANA land in a partnership that has substantial support from the region’s Native community.

Shively also served as an executive at AFN and once worked as commissioner of the Alaska Department of Natural Resources. Early in his career in the state, he worked on rural economic development and healthcare. In 1992, AFN gave Shively a Denali award — an honor reserved for non-Native people who have shown “strong commitment, dedication, and service” to Native people and rural Alaska.

But in recent decades, Shively has become most known for his work on Pebble — one of Alaska’s most controversial proposed mines, given its massive size and proximity to the world’s largest wild sockeye salmon fishery, at Bristol Bay.

Pebble would be among the world’s largest copper, gold and molybdenum mines, and boosters say it could create much-needed jobs and generate important revenue for the state and rural Alaskans. It has the support of two local Alaska Native corporations.

But many powerful political interests in the Bristol Bay area, including the Native regional corporation and multiple tribal governments, oppose the project. They say the mine would threaten salmon runs that sustain a huge commercial harvest as well as rural subsistence fishermen and Indigenous culture in the region.

As Pebble’s chief executive, Shively has worked “in opposition to Native self-determination and sovereignty,” said Alannah Hurley, executive director of United Tribes of Bristol Bay, a regional tribal consortium that’s opposed to the proposed mine. She called the First Alaskans Institute award choice “really disappointing.”

Two days after announcing the award, First Alaskans Institute released a statement saying that, in response to feedback from its community, the organization had contacted Shively to discuss the matter. He “graciously expressed appreciation for the recognition,” but “ultimately chose to decline the award,” the statement said.

Shively has worked extensively over the years with some Alaska Native leaders, including the chair of the First Alaskans Institute’s board, Willie Hensley. Hensley was an early leader at NANA and has served on an advisory committee for Pebble. He also sits on the board of a mining company, Trilogy Metals, that’s advancing a project near the end of another controversial development, the proposed Ambler road.

Hensley could not be reached for comment, and First Alaskans Institute’s staff declined to comment. Shively, in an interview, said the institute’s president, Roy Agloinga, had told him that the organization had received more opposition than it had expected after announcing the award.

Shively said he’s used to criticism, so the backlash didn't come as a complete surprise to him. But the ordeal has been “hurtful” to his family, he added.

In a since-deleted press release announcing that Shively had declined the award, First Alaskans Institute said its mission encompasses both resource development and conservation.

“We acknowledge and respect the many long-term contributions made by this individual,” the release said. “At the same time, we remain mindful of the concern among members of our community.”

If you like journalism like this piece, please consider a paid Northern Journal membership if you don't already have one.