Fact-checking Tom Cruise: Inside ‘Mission: Impossible’s’ trip to ‘Alaska’

Sure, there could be a secret CIA installation on a Bering Sea island. But taking a dog team across the surrounding sea ice? Only in Hollywood.

A reminder: Subscribe to the Northern Journal podcast! We've put out new episodes in the past few weeks on the Alaska LNG export project, the upcoming 2025 commercial salmon fishing season and, today, a new biography of Captain James Cook. If you're interested in advertising or underwriting either the podcast or an edition of Northern Journal, email publisher Nat Herz at nat[at]northernjournal.com.

The official, government story about St. Matthew Island, in the ocean waters off Alaska, is that it is uninhabited — famous, in fact, for being the most remote place in the state.

Which is exactly what the government would want you to think if they had actually set up a secret CIA station as part of a subsea listening network to monitor Russian submarines.

That, I was surprised to discover recently, is a key plot point in the new movie Mission: Impossible — The Final Reckoning — the latest installment in the multi-billion dollar franchise.

There I was, sitting in an Anchorage movie theater with some friends, when Tom Cruise and his band of sidekicks headed for the Bering Sea — part of their quest to retrieve a cache of computer code needed to thwart planetary destruction.

Of course, I had to write something.

The ideal, obvious Northern Journal take would be an in-depth q-and-a with Cruise about his envisioning of, and experiences with, Alaska. My requests to corporate publicists, however, went unheeded, so I settled on the next-best thing to an interview with Cruise : a fact-check. Just how plausibly did one of Hollywood’s most hyperbolic movie series render my home state?

A spoiler alert before we go any further: This piece will be discussing details of The Final Reckoning. If you want to remain ignorant of Cruise’s escapades before seeing the movie, stop here. While the things I’m about to reveal will not ruin the film’s climax nor your overall cinematic experience, it’s a Tom Cruise action movie, so of course it ends with him saving the world. Again. I did say spoiler alert.

Relevant plot points: In the previous Mission:Impossible movie, a Russian submarine is sunk by one of its own torpedoes and ends up on the ocean floor, its crew drowned. In the new film, Cruise’s character, Ethan Hunt, needs to retrieve the computer code from the wreck. But first, he has to figure out where the sunken submarine is .

So, he sends his longtime sidekick Benji, played by Simon Pegg, and pickpocket-love interest Grace, played by Hayley Atwell, to St. Matthew, where they find the CIA listening post. It’s staffed by an exiled operative living there with his wife — an Alaska Native woman played by Indigenous Canadian actress Lucy Tulugarjuk.

But Russian commandos have gotten there first. Shots are fired; the submarine’s location is determined and radioed to an American vessel carrying Cruise, who then dives deep into the ocean in an attempt to retrieve the computer code. Tulugarjuk’s and Atwell’s characters, meanwhile, take a dog team from the St. Matthew outpost across the sea ice, carrying a decompression chamber where Cruise can recover after his dive.

Let’s get into it.

First of all: Is there actually any active military infrastructure on St. Matthew?

No, says Dennis Griffin, a veteran archaeologist who’s visited the federally owned island three times and wrote a history of its human land use. Native people may have occasionally landed there there in ancient times, he said; fox hunters once traveled there, and there were also government weather and navigation stations on the island in the 1940s.

But those camps are all abandoned: An iconic photo taken by a researcher and posted on a U.S. Geological Survey website shows "what remains" of one of the St. Matthew outposts: a pile of rusted oil drums and a lonely toilet bowl sinking into the tundra.

A U.S. Geological Survey biologist took this photo of junk left behind from an abandoned U.S. Coast Guard navigational station on St. Matthews Island. A caption on the USGS website describes the toilet as “in nearly pristine condition.” (Laura McDuffie/USGS)

“It's really a bird refuge, so no one's allowed to live there,” Griffin told me by phone from Oregon, where he lives. There are fish in the streams, and foxes, and “little voles that sing” on St. Matthew, he said. “But it’s too far out for human habitation,” he added.

Scientists do visit St. Matthew, which is part of the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge, every few years, Griffin said. On his last trip with them, in 2018, no one reported finding a secret military installation, he added. “The bird biologists did transects right across the island,” he said. “And we would have seen that.”

But someone could have stumbled upon the CIA and been sworn to secrecy, though, right?

“Everyone who walked out there went as a team,” Griffin said. So, resident operatives “would have to bribe two people, if two people stumbled upon this covert operation.”

Case closed, or as closed as it’s going to be without me visiting St. Matthew to validate that Griffin isn’t on the CIA payroll.

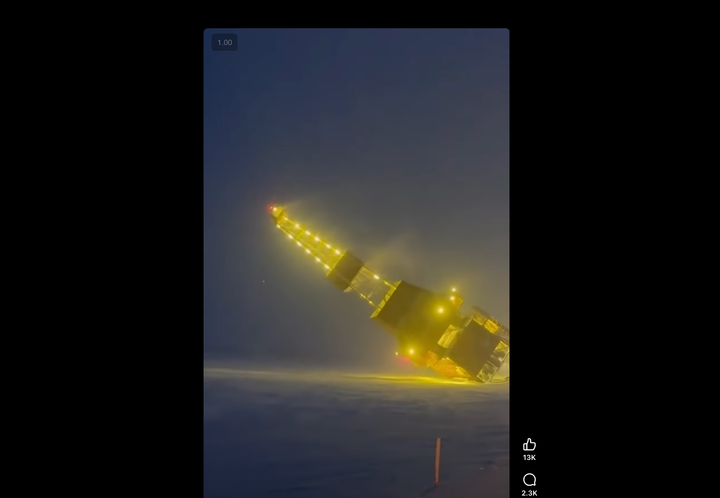

For what it’s worth: the scenes depicting the island were filmed not in Alaska but in Norway. Specifically, in Svalbard, the archipelago far above the Arctic Circle. The cast and crew stayed on a ship that carried them six hours north of Svalbard's hub town, where they lived near a glacier and saw walrus, reindeer and polar bears, according to one actor's interview with the Los Angeles Times.

Such charismatic megafauna also figure into the mushing trip shown in the movie: Tapeesa, the Indigenous character played by Tulugarjuk, at one point hands Atwell’s character a huge rifle and warns her about “nanuq,” the Iñupiaq word for polar bear.

I was skeptical that polar bears could be found as far south as St. Matthew. In fact, hundreds apparently lived on the island in the 19th Century, according to a contemporaneous report by a U.S. government official that was published in Harper’s Weekly. The resident bears are now gone, and reduced sea ice “has made it less and less likely” to find bears in the area, Lori Quakenbush, a marine mammal expert with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, told me in an email.

One plot strand that appears to be far less probable than marauding polar bears is the dog mushing expedition itself.

While sea ice does typically reach as far south as St. Matthew during the winter, it is not the kind of sea ice that you could take a sled across, according to Rick Thoman, a longtime Alaska climate researcher who also ran his own dog team as a young man.

The pack near St. Matthew is “jumbled,” Thoman told me. “It's thin. It's moving more or less constantly,” he said. “That would be brutal ice to take a dog team on.”

Another archival photo published by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service gives a pretty good impression. It shows an inflatable Zodiac raft, with an outboard motor, tucked into a small lead of open water off St. Matthew. A big shelf of ice looms over the raft on one side, while the ice on the other side looks to be flimsy and rotting — far from ideal mushing conditions.

Perhaps counterintuitively, the part of Mission: Impossible’s Alaska sojourn that feels most true to life could be the Cruise’s team’s encounter with Russian commandos.

The ensuing firefight might be overdramatic. But Chinese and Russian ships have been increasingly showing up in the Bering Sea in recent years, and members of Alaska’s congressional delegation have aggressively pushed the U.S. military to expand its presence in the region.

Disappointingly, neither of the spokespersons for Alaska’s two U.S. senators agreed to send their bosses to a screening of The Final Reckoning with me to facilitate further discussion. But I did talk with Paul Fuhs, a former mayor of the Aleutian Island town of Unalaska and an expert on shipping. And he told me I wasn’t too far off-base.

A full-scale invasion of Alaska by Russia during a global crisis? Not a chance, Fuhs said. But a smaller incursion, he added, is "entirely possible."

“Unless someone is on a satellite feed watching every single movement, sure — you could have people move in on one of these remote islands," he said. “They could be there for years without anyone picking up on it.”

Northern Journal's revenue comes from readers — voluntary paid memberships make up the majority of our revenue. Join if you can; if you already are a member, thank you.